Hypoglycemia is not an independent disease, but a clinical and laboratory syndrome. In diabetes, this condition occurs in approximately 40-60% of patients. Among people with type 1 diabetes, the percentage of cases of hypoglycemia is slightly higher, however, due to the much higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes, the predominant number of episodes of hypoglycemia occur in this form of diabetes. Moreover, in diabetes patients with prolonged hyperglycemia (decompensation), symptoms begin to appear already at a glucose level of 5-6 mmol/l. The maturing nervous system of children (especially newborns) uses more glucose and therefore reacts more acutely to hypoglycemia.

Causes of hypoglycemia

The condition has many etiological factors. In a healthy person, the reasons for a decrease in glucose below normal values may be pregnancy, intense physical activity, or prolonged fasting. However, such cases are extremely rare. Most often, hypoglycemia develops in various diseases and pathological conditions:

- Errors in insulin therapy for diabetes

. They are considered the most common cause of hypoglycemia. Basically, it develops if a patient who regularly injects himself with insulin skips meals, drinks alcohol, or begins to exercise. Sometimes the cause is a violation of injection technique, accidental or intentional overdose of insulin. - Hyperinsulinism.

Secretion of an inappropriately large amount of insulin into the blood by beta cells of the pancreas occurs in insulinoma, hyperplasia of the islets of Langerhans (nesidioblastosis). Also, the causes of excess production of insulin and insulin-like growth factor are some malignant tumors (carcinoma, mesothelioma). Hypoglycemia can occur in the presence of insulin autoantibodies that bind to insulin receptors (Hirata disease). - Endocrine disorders

. Deficiency of so-called contrainsular hormones, i.e. hormones with an antagonistic effect on insulin (cortisol, thyroxine, somatotropin) are observed in hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and pituitary dwarfism. - Taking medications

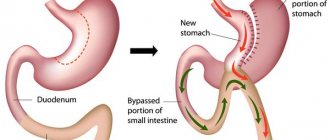

. In addition to insulin, other medications may cause a decrease in glucose concentration. First of all, these include medications used for type 2 diabetes (diabetic-lowering agents), which stimulate the production of insulin by the pancreas - sulfonylurea derivatives (glibenclamide), glinides (repaglinide). - Operations on the gastrointestinal tract

. Surgical interventions on the digestive organs, such as resection of the stomach or the initial part of the small intestine, lead to dumping syndrome, caused by the accelerated entry of undigested food into the intestines. As a result, insufficient breakdown and absorption of carbohydrates occurs. - Hereditary diseases

. These are severe metabolic diseases (glycogenosis, galactosemia, fructosemia), characterized by a genetically determined defect in enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (glycogen, fructose, galactose). As a result of enzyme deficiency, the conversion of glucose from other carbohydrates is impaired or its release from glycogen is impaired, which causes a drop in glycemic levels.

The development of hypoglycemia is predisposed by chronic diseases in which the clearance of glucose-lowering drugs that regulate blood glucose levels is slowed down - renal and liver failure. The hypoglycemic effect of sulfonylurea derivatives is enhanced when they are taken simultaneously with sulfonamides, salicylates, and synthetic antimalarials. Hypoglycemia is also caused by slow gastric emptying (diabetic gastroparesis).

Self-monitoring of general condition

Hypoglycemia is a condition that can be self-controlled when it is mild. Thus, people with type 1 diabetes monitor their blood sugar levels without the help of doctors and make the necessary adjustments. The diet for hypoglycemia consists of consuming foods with a low hypoglycemic index. It is recommended to avoid those foods that can cause a sharp jump in blood glucose levels. This list includes candies, cookies, cakes and other sweets with fast carbohydrates. They can be used in small quantities if the condition worsens.

Pathogenesis

Glucose is the main energy substrate for the central nervous system. Therefore, the central nervous system is very sensitive to hypoglycemia. First, as a compensatory reaction, counter-insular hormones are released into the blood, including catecholamines (adrenaline, norepinephrine), which cause vegetative symptoms. If glucose continues to be low, neuroglycopenia occurs.

Brain cells (mainly the cerebral cortex, diencephalic structures) begin to experience energy starvation, all metabolic processes, redox reactions, etc. are inhibited in them. Persistent hypoglycemia affects the medulla oblongata and the upper parts of the spinal cord, which leads to suppression of reflexes, convulsive readiness of the brain, impaired consciousness, and coma. Pathomorphological changes include edema, necrosis of certain areas of the brain.

Classification

Detection of hypoglycemia in a blood test is not always true. False, or pseudohypoglycemia, can occur with leukocytosis, erythrocytosis. Separately, transient hypoglycemia is distinguished in newborns born to mothers with diabetes. According to the severity, hypoglycemia is divided into mild, moderate, severe, and according to its course - acute, subacute, chronic. According to etiopathogenesis, the following types of hypoglycemia are distinguished:

- Lean (spontaneous)

. Develops with excessive secretion of insulin, insulin-like factor and diseases accompanied by a deficiency of contrainsular hormones. - Reactive (postprandial)

. Occurs 2-4 hours after eating. The cause is the early stage of diabetes, hereditary metabolic disorders, post-resection syndromes, autoimmune insulin syndrome. - Induced

. Develops in diabetes, caused by drinking alcohol and medications.

Symptoms of hypoglycemia

The presence of symptoms and their severity may not correlate with glycemic levels. The first symptoms are caused by activation of the sympatho-adrenal system (the release of adrenaline, norepinephrine). There is a sharp and strong feeling of hunger, muscle tremors, and sweating. The cardiovascular system reacts with increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, and angina pain in the heart. Neuropsychic symptoms are added: anxiety, motor agitation, depressed mood or, conversely, a feeling of euphoria.

Characterized by paresthesia (tingling sensation in the lips, tongue, fingertips). This is the so-called adrenergic or vegetative syndrome. If hypoglycemia continues, neuroglycopenia develops. Concentration and coordination of movements deteriorate (ataxia), speech becomes slurred and slurred. The patient begins to feel sleepy, he reacts poorly to external stimuli, sometimes photopsia (lightning flashes before the eyes) and visual hallucinations appear.

Tonic-clonic seizures, reminiscent of epilepsy, indicate deep depression of the nervous system and the patient’s extremely serious condition. The development of seizures precedes hypoglycemic coma. In individuals with chronic hypoglycemia (insulinoma), the only clinical manifestation may be an intermittent headache that quickly stops after ingesting a carbohydrate meal. When glucose concentrations decrease at night, some patients experience troubled sleep or nightmares. There are also atypical hypoglycemic symptoms - nausea, vomiting, bradycardia.

Clinical signs of low glucose levels

A drop in blood sugar, regardless of the cause, has symptoms:

- decreased intellectual abilities;

- disorientation, absent-mindedness;

- euphoria;

- drowsiness;

- lethargy;

- fog, spots before the eyes;

- a sharp, uncontrollable feeling of hunger.

When examining the patient, sweating, a jump in blood pressure, tachycardia, and pale skin are detected. If a hypoglycemic coma occurs, breathing, consciousness, and heart rhythm are impaired.

Complications

Severe hypoglycemia is characterized by a wide range of adverse effects with a high incidence of death. The most common of these include cardiovascular complications (hypertensive crisis, myocardial infarction, stroke) caused by the release of large amounts of catecholamines into the blood. Hypoglycemia can also cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, such as paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia, which is caused by prolongation of the QT interval. Complications of profound hypoglycemia include cerebral edema, coma, and respiratory and cardiac arrest.

Diagnostics

Endocrinologists are involved in the supervision of patients with hypoglycemia. At the initial appointment, the doctor asks the patient what medications he is taking and whether he has had any surgeries. During a general examination of the patient, attention is paid to the moisture of the skin, dilation of the pupils (mydriasis), suppression of physiological reflexes (tendon, skin) and the appearance of pathological ones (Babinsky reflex).

Organic hyperinsulinism (insulinoma, nesidioblastosis) is characterized by Whipple's triad: attacks of spontaneous hypoglycemia, a decrease in glucose levels during an attack below 2.8, rapid cessation of the attack by administering glucose or taking carbohydrates. The most difficult task is to establish the cause of hypoglycemia. For this purpose, an additional examination is prescribed, including:

- Laboratory research

. Blood tests measure C-peptide and glucose-insulin ratio. For diabetes, a glucose tolerance test and an analysis for glycated hemoglobin are performed. The presence of anti-insulin antibodies and antibodies to insulin receptors is checked. The concentration of counter-insular hormones is studied (thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, somatotropin, an ACTH test is performed). The activity of enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism (glucose-6-phosphatase, phosphofructokinase, glycogen synthetase) is studied. - Provocative tests

. Diagnosis of insulinoma is extremely difficult, so various provocative tests are often performed. The most informative test is a 72-hour fast. Stimulation tests are also carried out to suppress C-peptide after the administration of glucagon, leucine, and tolbutamide. - ECG.

The electrocardiogram reveals sinus tachycardia, atrial and ventricular extrasystoles, prolongation of the QT interval, and sometimes paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia can be recorded. With the development of myocardial ischemia due to excess catecholamines, ST segment depression and a negative T wave are noted. - Imaging of insulinoma

. In approximately 50% of patients, insulinoma can be visualized using ultrasound and CT scans of the abdominal cavity. Multislice tomography and intraoperative ultrasound are more sensitive. Selective pancreatic arteriography with the administration of calcium gluconate and subsequent blood sampling to measure insulin and glucose levels is recognized as a very effective diagnostic method.

Hypoglycemia should be differentiated from alcohol intoxication, epilepsy, vegetative crisis (panic attacks). It is also necessary to exclude stroke. An excited mental state and severe motor restlessness must be distinguished from mental disorders (hysteria, psychosis). In diabetes, it can be quite difficult to differentiate hypoglycemic coma from hyperglycemic coma based on clinical signs.

Treatment of hypoglycemia

Conservative therapy

To treat mild hypoglycemia, it is enough to take easily digestible carbohydrates - fruit juice, sweet tea, a few pieces of refined sugar. In case of moderate and severe severity, the patient must be hospitalized in the endocrinology department, and in case of depressed consciousness and coma - in the intensive care unit, where the following is carried out:

- Relieving hypoglycemia

. A glucose solution is administered intravenously; if the patient does not regain consciousness, drip administration continues. Intramuscular administration of glucagon is also effective (except for hypoglycemia caused by alcohol and sulfonylurea derivatives). Ascorbic acid is used to improve glucose utilization by neurons. To prevent cerebral edema in severe patients, magnesium sulfate, dexamethasone, and diuretics (mannitol or furosemide) are used. - Treatment of the underlying disease

. If the cause of hypoglycemia is a deficiency of contrainsular hormones, hormone replacement therapy (hydrocortisone, fludrocortisone, L-thyroxine) is performed. For autoimmune insulin syndrome, glucocorticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and plasmapheresis sessions are used. For the treatment of malignant insulinomas, if there are contraindications to surgery, the drug streptozocin is prescribed, which causes the death of beta cells of the pancreas. To improve the motor-evacuation function of the stomach in diabetes, prokinetics (itopride) are used.

Surgery

The most effective treatment for insulin and nesidioblastosis is surgery. In 90% of cases, the operation achieves a complete cure for the disease. The method of choice is tumor enucleation. Sometimes resection of the head, body or tail of the pancreas is performed. As a preoperative preparation, a powerful inhibitor of insulin secretion, diazoxide, is prescribed. Hyperglycemia is possible for 72 hours after surgery. To prevent it, short-acting insulin is administered. After removal of extrapancreatic tumors, glycemic levels return to normal very quickly.

Hypoglycemia and hypoglycemic coma

E.G. STAROSTINA

, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor.

MONIKA them. M.F. Vladimirsky The term “hypoglycemia” literally means “low blood sugar (glucose).

There is no uniform definition of hypoglycemia. In individuals who do not have diabetes mellitus (DM), hypoglycemia is defined as a decrease in blood glucose concentration to a level of less than 2.8 mmol/L in combination with certain clinical symptoms or to a level of less than 2.2 mmol/L regardless of symptoms. The features of determining hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes will be discussed below. Hypoglycemia can occur in the following situations:

1. Under the influence of hypoglycemic (antidiabetic) drugs, such as insulin and insulin secretagogues (oral hypoglycemic drugs of the sulfonylurea and glinide groups). 2. Under the influence of large doses of other drugs, one of the side effects of which is a decrease in blood glucose levels, for example, disopyramide, pentamidine, some antimalarial drugs, salicylates, etc., as well as ethyl alcohol intoxication. 3. In the presence of insulinoma - a tumor of the beta cells of the pancreatic islets that produce insulin. 4. With hyperplasia of the pancreatic islets (microadenomatosis and nesidioblastosis), also accompanied by hypersecretion of insulin. 5. For various diseases and syndromes accompanied by changes in the processes of gluconeogenesis in the liver, glucose utilization by peripheral tissues or the concentration of insulin and/or insulin-like factors in the blood, namely: 5.1. chronic cardiac, renal, liver failure; 5.2. septic shock; 5.3. hypofunction of the endocrine glands (hypothyroidism, adrenal, pituitary and endocrine polyglandular insufficiency); 5.4. large (usually more than 5 cm in diameter) tumors, both benign and malignant, for example, mesenchymal tumors, hepatoma, adrenocorticoblastoma, epithelial tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary system, lymphomas, etc.; 5.5. type B insulin resistance syndrome (presence of autoantibodies to insulin receptors), etc. 6. If the absorption of food carbohydrates is impaired or slowed down - after gastric surgery (dumping syndrome), diabetic gastroparesis. 7. Reactive hypoglycemia when eating foods rich in easily digestible carbohydrates.

The clinical picture of hypoglycemia and emergency measures themselves are practically independent of the cause that caused it. Most often in everyday practice we have to deal with hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes, which is the subject of this article.

The definition of hypoglycemia given at the beginning of the article is not always applicable to patients with diabetes. Some of them do not feel a decrease in glycemia even to a level of less than 2 mmol/l, while others - usually long-term decompensated - feel symptoms of “hypoglycemia” when glucose levels are above 4-5 mmol/l; the reasons for this are discussed below.

Hypoglycemia, which the patient manages to relieve on his own by taking carbohydrates, is classified as mild, regardless of the severity of the symptoms. Hypoglycemia is considered severe if recovery from it required the assistance of another person in the form of intravenous administration of glucose, or intramuscular or subcutaneous administration of glucagon, or oral administration of carbohydrates to a patient who could not eat on his own.

If a patient with diabetes receives drug glucose-lowering therapy and his target glycemic level is set at values close to normal, then when the target glycemic level is achieved, it is not possible to completely avoid hypoglycemia. In patients with diabetes with good compensation (glycated hemoglobin, or HbA1c, less than 7.0%), mild hypoglycemia can occur 1-2 times a week. The incidence of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes with an HbA1c of about 7.5% is about 0.15 (range 0.05 - 0.54) cases/patient per year. In elderly patients with type 2 diabetes receiving insulin, with an HbA1c level of 8.5%, the average incidence of severe hypoglycemia is 0.10 cases/patient per year. According to our data, the frequency of severe hypoglycemia in Russian patients with type 1 diabetes (HbA1 9.2% - 12.3%) ranges from 0.08 to 0.14 per patient per year, in patients with type 2 diabetes type – from 0 to 0.2 cases/patient per year.

Despite the high prevalence of hypoglycemia in general, severe hypoglycemia accounts for only 3–4% of the mortality rate in diabetes. The main clinical significance of hypoglycemia is that it is one of the main obstacles to achieving close to normal glycemic levels necessary for the prevention of late vascular complications of diabetes.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Normal blood glucose concentration is maintained if the entry of glucose into the bloodstream is equal to the disappearance of glucose from the blood. Consequently, the main cause of hypoglycemia is an excess of insulin in the body in relation to the supply of glucose from the outside (with food) or from endogenous sources (liver), as well as in relation to the accelerated absorption of glucose by tissues (muscle work). Factors that cause an imbalance between the amount of insulin and glucose in the blood are listed in Table 1.

The most common of them can be considered three: discrepancy between the dose of insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs (from the sulfonylurea and glinide groups) and the amount of carbohydrates taken, unplanned physical activity above the usual level, and alcohol intake. Other oral drugs, when used alone, usually do not or very rarely cause severe hypoglycemia.

The main risk factor for severe hypoglycemia is the lack of easily digestible carbohydrates for immediate relief of mild hypoglycemia (insufficient patient education). In addition, the risk of severe hypoglycemia increases in patients with a history of repeated severe hypoglycemia, as well as in the absence of residual insulin secretion, long-term diabetes, loss of sensation of hypoglycemia symptoms, terminal diabetic nephropathy, old age and low social status of the patient.

Normally, in a healthy person, the first electrophysiological signs of a brain reaction are recorded when glycemia decreases to 3.8 mmol/l, but the brain does not yet experience a lack of glucose. At a glycemia of about 3.8 mmol/l, the secretion of counter-insular hormones begins to increase, aimed at maintaining normal glucose levels. The secretion of contrainsular hormones increases in the following order: glucagon, then, if the effect of glucagon is insufficient, adrenaline. Growth hormone and cortisol respond only with longer duration of hypoglycemia. Activation of the autonomic nervous system when blood glucose decreases to approximately 3.3 mmol/l is manifested by the so-called. "vegetative" symptoms of hypoglycemia. At a level of about 2.7 mmol/l, symptoms of insufficient glucose supply to the brain (neuroglycopenia) occur. With a very rapid drop in glycemia, autonomic and neuroglycopenic symptoms occur simultaneously.

In patients with short-term diabetes, the above-described counter-regulation system during hypoglycemia functions in the same way as in healthy individuals. With long-term diabetes, this function may be impaired: first of all, the secretion of glucagon decreases, and later adrenaline, which increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia. The counter-regulatory system may not function when the concentration of insulin in the blood is high. For these reasons, patients with diabetes should never expect hypoglycemia to stop on its own; active and immediate measures should always be taken to stop it.

The release of counterinsular hormones causes relative insulin resistance after hypoglycemia, leading to increased blood glucose levels (Somogyi phenomenon). Its clinical significance as a cause of morning hyperglycemia has been overestimated. In fact, the Somogyi phenomenon is not too pronounced: it increases glycemia by no more than 1.1–4.4 mmol/l and is observed only in patients with an adequately functioning contrainsular system, i.e., in well-compensated patients with a short duration of diabetes . On the contrary, with decompensated diabetes and impaired counterregulation, the Somogyi phenomenon almost never occurs. Most often, posthypoglycemic hyperglycemia develops due to the intake of excess carbohydrates during hypoglycemia. A mistake in this case is the introduction of additional amounts of insulin, which can cause repeated hypoglycemia. Even more often, morning hyperglycemia occurs due to the insufficient effect of the evening dose of extended-acting insulin, since the need for insulin from 5 to 8 a.m. increases under the influence of the physiological circadian rhythm of secretion of counter-insulin hormones (“morning dawn”). With hypoglycemia, there is a compensatory increase in cerebral blood flow by 2–3 times, so most cases of mild hypoglycemia are not accompanied by irreversible consequences of a lack of glucose in the cells of the cerebral cortex. Unlike mild hypoglycemia, severe hypoglycemia increases the risk of cardiovascular, neuropsychic and other complications, although with severe hypoglycemia, even repeated ones, they do not always develop. Contrary to popular belief, hypoglycemia is not the cause and does not aggravate the course of diabetic microangiopathies, in particular retinopathy. Thus, in the seminal Diabetes Compensation and Complications Study (DCCT), long-term maintenance of near-normal glycemic levels significantly slowed the appearance and progression of microangiopathies, although it was accompanied by an increased incidence of severe hypoglycemia.

Clinic

Autonomic symptoms (precursor symptoms) of hypoglycemia include heartbeat, trembling, pale skin, increased sweating, nausea, severe hunger, anxiety, aggressiveness, mydriasis, tingling sensation (usually lips, tongue, fingertips). Neuroglycopenic symptoms include weakness, impaired concentration, headache, dizziness, paresthesia, fear, disorientation, speech, visual, behavioral disturbances, amnesia, impaired motor coordination, confusion, coma, convulsions. Not all symptoms occur with every hypoglycemia; its picture may vary in the same patient. The features of alcoholic hypoglycemia include the difficulty of its recognition by the patient and others due to the great similarity of subjective and objective symptoms of hypoglycemia and intoxication, delayed onset and protracted course, and the possibility of repeated hypoglycemia. The last three signs are also characteristic of hypoglycemia caused by prolonged physical activity. The faster your blood glucose levels drop, the more severe your symptoms usually become. The individual glycemic threshold at which autonomic and neuroglycopenic symptoms appear may vary. Thus, with prolonged decompensation of diabetes, patients may experience hypoglycemia at 5–7 mmol/l, i.e., in the absence of true hypoglycemia. After gradual improvement in compensation, the threshold for the sensation of hypoglycemia in such patients is normalized. On the other hand, persistently too low glucose levels can lead to decreased perception of hypoglycemia; in this case, the reduction in the sensation of hypoglycemia is also reversible if hypoglycemia is avoided. There are initially asymptomatic hypoglycemia, which either go away on their own or end in a “sudden” loss of consciousness. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Since the clinical picture of hypoglycemia is nonspecific and variable, its diagnosis requires laboratory confirmation. This is especially true for nocturnal hypoglycemia; basing its diagnosis on indirect signs (sweating, anxious sleep, “food” or nightmares) is not enough. Laboratory confirmation is especially important because often patients with very high hyperglycemia, i.e., those with severe insulin deficiency, experience severe hunger (glucose does not enter the cells due to insulin deficiency), and may complain of sweating and palpitations (with vegetative diabetic neuropathy, with long-term decompensated diabetes). Without laboratory glycemic monitoring, these clinical signs are mistakenly interpreted as hypoglycemia and the insulin dose is reduced instead of increased. A blood glucose test during a seizure and a routine EEG are required to differentiate between severe hypoglycemia with seizure and epilepsy; a combination of these two forms of pathology is possible. Another “mask” of mild hypoglycemia with clinically indistinguishable autonomic symptoms is panic attacks; here, a differential diagnosis is impossible without determining glycemia during the presence of symptoms. After prolonged severe hypoglycemia, a neurological examination, including computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, is indicated.

Treatment

Mild hypoglycemia can be stopped by taking simple carbohydrates in the amount of 1.5–2 bread units (1 XE equals 10–12 g of carbohydrates). This amount of carbohydrates can be taken in the form of sugar (12–20 g, better dissolved in water or tea), or honey, or jam (1.5–2 tbsp.), or 200 ml of sweet fruit juice, or 100 ml lemonade (or Pepsi-Cola, Fanta, etc.), or 5 large glucose tablets (a convenient option is a pack of 10 tablets of 3 g in the form of “candy”).

A patient receiving insulin, sulfonylureas or glinides should always have easily digestible carbohydrates with him. Taking 2 bread units will increase glycemia to a level of at least 5 mmol/l, i.e. to the full norm. This is important to know so as not to eat more than the required amount of XE. However, it should be remembered that the greater the dose of insulin that caused hypoglycemia, the more carbohydrates are needed to normalize glucose levels. Up to 3-4 bread units will be required if hypoglycemia develops in the morning on an empty stomach or after prolonged physical activity, because in these cases the glycogen content in the liver is low, therefore, its “contribution” to relieving hypoglycemia will be extremely small. If hypoglycemia is caused by the action of long-acting insulin, especially at night, then after its relief, you additionally need to eat 1 more bread unit of slowly digestible carbohydrates (a piece of bread, 2 tablespoons of porridge, etc.), to “insure” repeated hypoglycemia at night.

In case of severe hypoglycemia, the unconscious patient should be placed on his side and the oral cavity should be cleared of food debris; Do not pour sweet solutions into the oral cavity (risk of aspiration and asphyxia). 40% glucose is injected intravenously in an amount of 20–30 ml (maximum up to 100 ml) until consciousness is restored. An alternative, especially at home before the arrival of the medical team, is the subcutaneous or intramuscular injection of 1–2 ml (1–2 mg) of glucagon, which is available in the form of syringe tubes filled with a solution. The patient's relatives or friends should administer the glucagon drug, which greatly simplifies and speeds up the recovery of the patient from an unconscious state. One milligram of glucagon increases glycemia by an average of 8.5 mmol/l; consciousness is usually restored within 5–10 minutes after administration. Glucagon stimulates the endogenous production of glucose by the liver, so its effect requires the presence of glycogen in the liver. It will be ineffective for alcoholic hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia caused by massive overdose of insulin or sulfonylureas. In the first case, the production of glucose by the liver will be blocked by ethanol, in the second - by insulin.

If consciousness is not restored after intravenous administration of 100 ml of 40% glucose, then intravenous drip administration of 5–10% glucose is started and the patient is hospitalized. Other indications for hospitalization include the absence of a clear cause for hypoglycemia, overdose of sulfonylureas, nocturnal severe hypoglycemia, and signs of neurological deficit. If the first measures to relieve severe hypoglycemia do not restore consciousness, it is necessary to exclude a massive overdose of hypoglycemic drugs, intoxication (alcohol, sedatives and hypnotics) and other causes of loss of consciousness that could be provoked by hypoglycemia, primarily cardiovascular, stroke, craniocerebral injury. If consciousness is not restored after 4 hours, cerebral edema and an unfavorable outcome are very likely.

Hypoglycemic coma can be delayed if it is caused by excessive alcohol intake, overdose of long-acting insulin and long-acting sulfonylureas (for example, glibenclamide), especially in elderly patients or with concomitant renal impairment. Intravenous drip administration of 10% glucose, alternating with a 40% solution to avoid fluid overload, should be continued as long as necessary to normalize glycemia. In case of an overdose of sulfonylurea drugs, it is necessary to perform gastric lavage and prescribe enterosorbents; in case of a massive overdose of insulin, surgical excision of the injection site is performed (this is advisable to do if no more than 2-3 hours have passed since the overdose).

The main errors in the diagnosis and treatment of hypoglycemia are associated with the lack of laboratory confirmation. It is also a mistake to fail to determine glycemia in any patient with a sudden disturbance of consciousness, paresis, convulsive attack, pretentious or aggressive behavior. If it is not possible to measure glycemia, empirical intravenous administration of 40% glucose and other measures based on the presumptive diagnosis of hypoglycemia are indicated. In case of hypoglycemia, they will be adequate, and in other conditions, including diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, this amount of glucose will not worsen the patient's condition.

The administration of thiamine (vitamin B1) for severe hypoglycemia as such in a patient with diabetes is not pathogenetically justified and has no proven clinical significance. Thiamine in a dose of 100 mg is indicated only for those patients with severe hypoglycemia who have a high probability of vitamin B1 deficiency and the development of Wernicke encephalopathy, namely: a) with chronic alcoholism and the presence of at least one symptom of Wernicke encephalopathy (vomiting, nystagmus, mono- or bilateral ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, fever); b) in regions where beriberi disease occurs - vitamin B1 deficiency; c) in the presence of malnutrition (nutritional malnutrition).

Adrenaline or glucocorticoids are not indicated for prolonged severe hypoglycemia, and here's why. As already noted, every 15–20 g of glucose increases glycemia by 3.8 mmol/l. Therefore, 60–100 mL of 40% glucose (24–40 g glucose) will increase glycemia by 4–7 mmol/L and should restore consciousness in any patient with uncomplicated severe hypoglycemia. If this does not happen, it remains to assume either a concomitant “non-hypoglycemic” cause of loss of consciousness (then adrenaline or corticosteroids to increase glycemia are not indicated even theoretically), or that severe hypoglycemia is caused by a massive overdose of glucose-lowering drugs. In this case, adrenaline and corticosteroids will also not increase glycemia, since their mechanism of action is to stimulate the production of glucose by the liver, and with a massive overdose, the liver is completely blocked and cannot release additional amounts of glucose into the blood even when stimulated by adrenaline and steroids. Dexamethasone can be administered during prolonged severe hypoglycemia only to prevent cerebral edema if a concomitant intracranial catastrophe is suspected, but not to relieve hypoglycemia itself.

Prevention

Every patient with diabetes who receives hypoglycemic drugs (especially insulin, sulfonylureas, glinides) should know the symptoms of hypoglycemia, its causes, trigger factors, rules for relief and prevention. Even during their hospital stay, patients who are prescribed insulin for the first time should experience mild hypoglycemia in order to know what symptoms arise. Hypoglycemia can be deliberately induced, for example by physical exercise before meals.

The most important indicator of a patient’s adequate behavior in relation to diabetes is the constant presence of easily digestible carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are considered present only if the patient can directly present them to the doctor during the interview. To develop and maintain this skill, it is recommended that at each outpatient visit, the doctor always asks the patient to show the carbohydrates that he carries with him in case of hypoglycemia. Literature

1. Berger M., Starostina E., Jorgens V., Dedov I. Practice of insulin therapy. Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany. 1995. 2. Potemkin V.V., Starostina E.G. Guide to emergency endocrinology. M.: Medical Information Agency, 2008. 3. Starostina E.G. Acute complications of diabetes mellitus // Diabetes mellitus: acute and chronic complications / ed. I.I. Dedova, M.V. Shestakova. M.: LLC Publishing House “Medical Information Agency”, 2011. P. 25–58. 4. Bledsoe BE No more coma cocktails. Using science to dispel myths & improve patient care // J. Emerg. Med. Serv. 2002. No. 27(11). R. 54–60. 5. DCCT Research Group: Epidemiology of severe hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial // Am. J. Med. 1991. No. 90. R. 450–459. 6. Mühlhauser I., Overmann H. et al. Risk factors of severe hypoglycemia in adult patients with Type 1 diabetes – a prospective population based study // Diabetologia. 1998. No. 41. R. 1274–1282. 7. Mühlhauser I. Hypoglykämie // Berger M. Diabetes Mellitus. 2 Aufl. Urban & Fisher, Muenchen-Jena. 2000. R. 370–386.

Prognosis and prevention

Despite the significant number of complications, in most cases hypoglycemia is mild or moderate in severity. In diabetes, it accounts for only 3-4% of the mortality rate. The main cause of death is cardiovascular accidents (heart attack, stroke). To prevent hypoglycemia in diabetes, the patient must strictly adhere to the dosage, technique and frequency of insulin administration, not skip meals, and avoid drinking alcohol.

When carrying out insulin therapy, you need to regularly monitor your blood glucose level with a glucometer, and have quickly digestible carbohydrates with you to independently relieve hypoglycemia. It is also necessary to competently select the dose of glucose-lowering drugs, taking into account the patient’s liver and kidney function and possible drug interactions. For patients with metabolic disorders (glycogenosis, galactosemia), frequent split meals with large amounts of carbohydrates are recommended.

How to check?

“Methods of self-monitoring of blood glucose at home using glucometers are now widespread. But, unfortunately, such devices may have measurement errors, and it is not always possible to see critical blood glucose levels. Therefore, if you experience repeated symptoms of hypoglycemia and low blood sugar levels during any measurement, it is better to consult an endocrinologist for examination and clarification of the reasons,” the doctor advises.

Hypoglycemia is a frequent companion of people with diabetes mellitus, especially with a long history, as well as people receiving insulin or drugs that stimulate increased secretion (release) of insulin.

Insulin and penicillin: 5 discoveries that changed the world Read more