About cephalgia

Most often, cephalalgia is a symptom of another disease; independent pathologies based on headache include cluster pain and migraine

Cephalgia is pain in the skull area of varying localization and intensity. Today, more than 200 types of headaches are distinguished depending on the cause of its occurrence, the severity of the pain syndrome, pathological changes in the blood vessels of the brain, etc.

People at any age experience cephalalgia. Women are prone to headaches more often than men, but among the stronger sex the pain syndrome is more intense.

Interesting! Despite the fact that a headache often spreads deep into the skull, a person’s brain cannot hurt, since it has no pain receptors.

Cephalgia develops due to irritation of only 9 areas. Most often, headaches are the result of irritation of pain receptors in the periosteum, arteries or sinuses.

There are many codes for headaches in ICD-10. Cephalgia in adults is classified according to ICD-10 depending on the cause. Thus, code G44 indicates cephalgic syndrome of various etiologies - from “histamine” headache to chronic cephalgic syndrome. Any cephalgic syndrome, the cause of which is not included in the list of diseases given in the classifier, will have an international ICD code G44.8. In addition, there is a separate international classification of headaches, adopted in 2003, which lists all types of cephalgia.

To effectively get rid of a headache, it is necessary to identify the cause of its occurrence. Despite the fact that analgesics help with cephalalgia, they do not provide a long-term effect, since they do not affect the cause of the pain syndrome. A neurologist can accurately diagnose and identify pathologies leading to headaches.

Headache in a child

Headache (cephalgia)

among children is one of the five most frequent visits to the doctor. Complaints can begin from the age of two, and, according to pediatricians, already 45-50% of seven-year-old children experience periodic headaches. And at the age of 15 years, up to 80% of children upon examination complain of headaches.

In our country, doctors usually give a child suffering from cephalgia one of the following diagnoses:

- autonomic dystonia syndrome;

- hypertensive-hydrocephalic syndrome (syndrome of increased intracranial pressure);

- instability of the cervical spine;

- consequences of traumatic brain injury (post-traumatic arachnoiditis).

Unfortunately, according to doctors, in 35% of children it is impossible to make a correct diagnosis at all, since it is not possible to classify pain according to the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) criteria. As a result, in many cases, therapy is prescribed that has nothing to do with the true cause of pain and more often has a placebo effect. Fortunately, children have enormous recovery capabilities of the body.

Types of headaches

According to the 2013 International Classification of Headaches in Children, primary and secondary headaches are distinguished. The primary ones include tension headache (up to 40% of the total number of registered complaints in children), migraine (up to 25% in the structure of headaches) and cluster headache (which is more of a casuistry than the norm). Secondary headaches include headaches due to infections (most often upper respiratory tract infections), large tumors, vascular malformations (congenital disorders of the circulatory system), injuries and those associated with psychogenic factors.

Also, headaches can be caused by vision problems, such as myopia, that are not promptly monitored by parents and doctors. In general, cephalgia in children is often secondary.

Based on the manifestations, doctors distinguish:

- acute recurring headache (the most common causes: migraine, epilepsy);

- acute diffuse (infectious etiology, systemic pathology, subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis);

- acute localized (sinusitis, trauma, ophthalmological pathology);

- chronic progressive (serious neurological pathology - space-occupying formation or vascular pathology, chronic hydrocephalus, abscesses, intoxication);

- chronic non-progressive (depression, tension headaches, anxiety and other psychological factors);

- mixed headache (migraine plus other causes).

The increase in the prevalence of headaches in children in the last half century, on the one hand, is due to serious changes in lifestyle: an increase in the intensity of stress at school, disturbances in sleep and nutrition, a decrease in physical activity, prolonged periods of time at the computer, and an increase in the number of stressful influences. On the other hand, medical problems related to the lack of timely diagnosis of diseases and effective treatment planning are still relevant.

Features of cephalalgia in children

Let's take migraine, for example. All neurologists who have read JK Rowling's books or watched the film adaptation agree on one thing - the fictional character, Harry Potter, clearly suffered from a common form of migraine called "migraine with aura" (although in a fit of enthusiasm, doctors came up with at least 7 reasons that could cause pain in the character, ranging from subarachnoid hemorrhage to incorrect selection of glasses).

In boys, migraine begins more often at the age of 6–7 years; in girls, the onset of the disease occurs at 10–11 years. At the same time, there is definitely a person in the family who suffers from migraines (if the mother has migraine, the child has a 60–70% chance of having it, if the father has it, 30%; both parents have 90–95%). Children, as a rule, do not have characteristic pain in half of the head and do not have a characteristic “adult” attack. Attacks can be very short (up to a few minutes) and... go away forever with age!

At one time, the media wrote a lot about the fact that actor Daniel Radcliffe also often has seizures, “because of which he has to swallow handfuls of pills.” Even the term “Hogwarts headache” has appeared; it refers to cephalgia associated with an unusual activity for modern children - quickly reading a large amount of information. For example, the weighty books of the prolific writer (the first 309 pages, subsequent ones up to 870), “voraciously devoured” by schoolchildren, turned out to be a difficult test for them.

By the way, do you remember who Harry complained about his headaches to in the book? That's right - no one! Like most children, unfortunately...

Main triggers (attack provocateurs)

Parents need to know that cephalalgia in children is most often provoked by the following factors:

- Stress

(both positive and negative emotions) and muscle tension. By the way, regular aerobic exercise “until the second sweat” - but not “until the seventh”! - strengthens the nervous system well and reduces the number of attacks by at least half. But significant physical activity and pronounced muscle tension (for example, in the neck muscles when reading) - on the contrary, provoke attacks. I already wrote above about “binge reading,” but the same applies to computer and sports hobbies—everything is good in moderation. But some children have a more intensive daily routine than an adult! - Irregular meals.

Lack of a full breakfast or lunch is a very common cause of headaches in children. To significantly reduce the number of attacks, it is necessary to normalize your diet. - Non-compliance with the daily routine.

Doctors call it the "Monday morning migraine." All parents know about the importance of sleep hygiene, but few follow doctors' recommendations in practice. Meanwhile, the correct sleep schedule and a sleep duration of 8–10 hours are very important for effectively helping all children with headaches. A “floating” daily routine is also a pronounced provoking factor for cephalgia. - Some foods

can cause an attack of cephalalgia in children: cheese, chocolate, citrus fruits, fast food, ice cream, aspartame, carbonated drinks with dyes, sausages, smoked meats, yoghurts not suitable for children and almost all products containing caffeine.

It should be noted that a headache in itself is stressful for both the child and his parents, so remember that the anxious anticipation of an attack of pain can also provoke this attack!

Difficulties in diagnosis

Almost until adolescence, a child cannot clearly explain his complaints (pulsating pain? squeezing? pressing? what? - no answer. This is considered a limited description of the headache pattern and makes diagnosis difficult), in addition, children are often confused about the location of the pain.

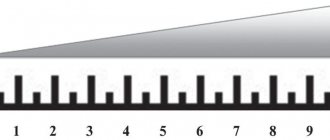

The doctor cannot use the VAS (Visual Analogue Pain Scale). For a child, giving a 4 or an 8 on this scale can be a completely incomprehensible process or game. He may not complain specifically about a headache, but present some nonspecific complaints (fatigue, darkening of the eyes, nausea), which, when associated with other diseases, can also lead the doctor too far in his assumptions.

First of all, the attentiveness of parents will help in diagnosis. You need to remember (for this it is best to keep a diary) and succinctly tell the doctor how long, over what period (weeks, months) headaches have been observed, with what regularity the headaches hurt, in what way and how severely, where the pain is localized, what exactly affects on its appearance (hunger, physical activity) and weakening, whether the headache is accompanied by other complaints (nausea, dizziness, fear of light and sound), what the child looks like during an attack (pallor, redness of the face, dark circles under the eyes), what medications the child takes . Sometimes you can ask your child to draw his pain. A drawing can tell a specialist a lot.

Should I take my child for an MRI?

It should be noted that in children in whom the neurologist did not find any alarming symptoms during a neurological examination, most often (in 99%) no abnormalities are found during hardware studies (CT, MRI). But don't forget about this single percentage. Therefore, if the doctor insists on neuroimaging, you need to do it as soon as possible.

The absolute indications for MRI are:

- headache for more than 6 months without response to treatment;

- combination of pain with deviations in neurological status;

- night headache with awakenings;

- headache in combination with disturbances of consciousness, vision and vomiting;

- no family history of migraine;

- family history.

When you urgently need to see a doctor

Parents should know that a child’s headache is most dangerous if:

- pain began before age 5 years;

- when the number of attacks sharply (in less than 2 months) increased;

- pain is localized in the occipital region;

- is bursting and sudden in nature;

- has a pronounced intensity.

Don't believe that children don't have strokes! A “thundering” headache that grows to extremely intense within a minute is most often caused by a vascular accident in the brain. The child should be taken to the hospital as quickly as possible.

Ambulances

The need for an anesthetic drug appears if the attack does not go away within 30–40 minutes of rest (for migraines - 20 minutes) or a short sleep, also if the pain increases mildly. It is important to know what medications can be used to relieve pain in children. Suitable medications include ibuprofen (children's Nurofen, etc.) and acetaminophen (paracetamol, etc.) in age-specific dosages. For children over 5 years old, after taking medication (tablets or suspensions, suppositories or injections), it is necessary to take at least 300 ml of liquid.

You cannot use drugs containing acetylsalicylic acid, metamizole sodium, no-shpu and combined analgesics (especially those containing caffeine and phenobarbital), since they are rare in children under 15 years of age, but can lead to quite severe complications. If the headache is not relieved by taking simple analgesics, you need to consult a specialist to select effective and safe therapy. Nootropics and vitamins for headaches act as placebos! Don't stuff your children with them unnecessarily!

Valentina Saratovskaya

Photo thinkstockphotos.com

Products by topic: [product](ibuprofen), [product](nurofen), [product](paracetamol)

Symptoms in children and adults

Having figured out what it is - cephalalgia of the brain, you should know how it manifests itself. Cephalgic syndrome is characterized by pain of varying intensity and duration in different parts of the skull. The exact symptoms depend on the cause of the cephalalgia.

Chronic cephalgia is a constant aching headache. They can manifest themselves under the influence of any factors or arise spontaneously. Most often, such headaches are associated with stress.

Migraine (hemicrania) is a primary headache of a paroxysmal nature, the causes of which cannot be associated with other neurological disorders. It is characterized by severe pain in one side of the head, which is accompanied by light sensitivity of the eyes and nausea. Migraine is characterized by a specific set of symptoms preceding the onset of pain - an “aura.”

Cephalgic syndrome against the background of high blood pressure is manifested by throbbing pain in the back of the head, and against the background of low blood pressure - a dull aching pain in the temples.

Cephalgia syndrome manifests itself equally in children and adults; specific symptoms depend on the cause and type of headache.

Classification of headaches, causes

The most common types of headaches are tension headaches and migraines, as well as post-traumatic headaches

In general, cephalgic syndrome is divided into two large groups - primary and secondary headaches. The primary ones include migraine, tension headache, and autonomic cephalgia.

The second group of secondary headaches includes cephalgia associated with:

- head, spine and neck injuries;

- vascular pathologies of the brain and neck;

- non-vascular brain lesions;

- taking certain medications and chemicals;

- infectious diseases;

- mental illness.

In fact, the same classification describes the causes of headaches.

The cause of primary headache is unknown. Interestingly, migraines can be genetic in nature, and are passed on from woman to daughter. Thus, there are many cases where mother and daughter suffered from migraine attacks of the same intensity and frequency.

Secondary cephalgic syndrome may result from:

- mental disorders;

- autonomic dysfunction;

- hypertension;

- hypotension;

- skull injuries;

- spine pathologies;

- osteochondrosis of the cervical spine;

- vascular lesions of the brain;

- inflammation of the membranes of the brain;

- infectious brain lesions;

- lesions of the facial nerve;

- inflammation of the sinuses, etc.

The full list of causes of headaches is very long. Cephalgic syndrome in children often occurs against the background of diseases of the middle ear (otitis media), sinusitis. Cephalgic syndrome in older people may be a consequence of glaucoma.

Note! Severe strabismus in young children can cause the development of secondary cephalgic syndrome.

Cephalgia in children and adults can be associated with head and back injuries. Women of reproductive age often experience headaches due to hormonal changes.

In young children, cephalalgia can also be a symptom of minimal brain failure.

To accurately understand the causes and manifestations of cephalgic syndrome, you can consider the most specific types of headaches.

Migraine

Migraine is manifested by paroxysmal recurrent headaches of a pulsating nature, more often it affects the parieto-occipital or frontotemporal region, less often it is bilateral

This type of headache is classified as primary, since the exact cause of its development is unknown. Migraine is characterized by attacks, the frequency of which depends on a number of factors. For some people, specific smells, loud sounds, and bright lights are triggers for the onset of an attack.

A characteristic feature of such a headache is the presence of an aura. This is a set of symptoms that precede the onset of an attack. The aura is manifested by a sudden increase in photosensitivity, nausea, irritability, and mood swings. The pain syndrome of migraine is severe, the pain is concentrated in one (right or left) part of the head. The attack can last from several hours to several days. A distinctive feature of this cephalalgia is that treatment with analgesics is practically ineffective.

Coital cephalalgia

As the name implies, coital cephalgia occurs only at the time of sexual activity. Women most often experience this type of headache. Discomfort occurs either during lovemaking due to compression of the spinal artery, or when the body tenses during orgasm.

This type of headache appears spontaneously and goes away in an average of half an hour. The pain syndrome can be so severe that it forces a person to completely refuse intimacy. Coital cephalgia does not pose a threat to life, but greatly impairs its quality. An attack can be prevented by taking an analgesic before sexual intercourse.

Vasomotor cephalgia

This type of headache is associated with stress, muscle hypertonicity, depression and neuroses. Vasomotor cephalgia is manifested by pain on both sides of the head. The pain is constant, without pulsation or peaks, and is accompanied by deterioration of cognitive functions - memory and ability to concentrate. Severe vasomotor cephalgia may be accompanied by impaired coordination of movement due to muscle stiffness.

Vasomotor cephalgia is also called tension headache.

Vascular cephalgia

The most common vascular cephalgia is pain that occurs as a result of dilation of the blood vessels in the brain and it seems as if hammers are knocking inside the skull.

This type of headache develops due to the overflow of blood vessels in the brain due to their expansion. Vascular cephalgia is observed with increased blood pressure, severe physical exertion, and stressful situations; any conditions associated with the release of adrenaline. Vascular cephalgia, which occurs as a result of blood vessels overflowing, is characterized by pulsation in the back of the head, which intensifies with exercise.

Vestibulo-atactic cephalgic syndrome is a severe disorder that often occurs in children. Vestibulo-atactic syndrome develops against the background of dropsy of the brain, osteochondrosis of the neck, and hypertension. This is a severe form of vascular cephalgia, which is accompanied by vestibular disorders that affect coordination of movements. This disorder is characterized by flickering of spots before the eyes, dizziness, and deterioration in performance. The pain may appear sporadically or be constant. In the second case, we are talking about persistent cephalgic syndrome, which requires qualified treatment.

Neurological and mental headache

Autonomic cephalgia is the so-called headache of weather-dependent people. As a rule, the disorder is not an independent disease, but is part of a symptom complex of autonomic dysfunction (vegetative-vascular dystonia, neurocirculatory dystonia).

Note! It is incorrect to call vegetative-vascular dystonia a disease; it is not in the ICD, and such a diagnosis is not made today.

Doctors consider autonomic headaches as a symptom of a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

Asthenocephalgic syndrome is a headache associated with mental disorders or severe stress. It often accompanies panic attacks, phobic and anxiety disorders. Such cephalgia in a child often occurs during adolescence and goes away without treatment as the nervous system strengthens.

Tension headaches in children, adolescents and adults: the role of NSAIDs

Tension type headache, or simply tension headache (TTH), is a common pathology in patients over 5 years of age [1]. This is a variant of primary headache (cephalgia), which occurs in response to mental stress resulting from acute or chronic stress [1, 2].

Mental stress during TTH can be combined with tension in the muscles of the scalp (frontal, temporal, occipital), which form the helmet of the head. TTH occurs in all age groups (it is more often observed among females) [1–3].

Basic information about HDN

Currently, in neurological practice it is customary to use the International Classification of Headache II Revision (ICHD-II), proposed in 2003 [4]. TTH belongs to section 1 “Primary headaches” (along with migraine and other primary cephalgia) [4]. In 2013, the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) presented an updated version of ICHD-III (the so-called “beta version”), which is currently not yet considered complete and final [5] . Like the predecessors of ICHD-III (ICHD-I and ICHD-II), this classification does not fully correlate with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), used in practice to code diagnoses [6].

ICD-10 currently provides the following main codes for categorizing HDN:

- G44.2 Tension headache (tension type): frequent, infrequent, chronic.

- G44.20 Infrequent episodic tension-type headache associated with pericranial muscle tension.

- G44.21 Frequent episodic tension-type headache.

- G44.22 Chronic tension-type headache, combined with tension of the pericranial muscles.

- G44.23 Chronic tension-type headache, not combined with tension of the pericranial muscles.

- G44.28 Possible TTH (possible frequent, possible infrequent, possible chronic TTH) [6].

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has proposed the following criteria for tension-type headache:

1) the duration of the TTH episode is not <30 minutes (for episodic TTH - from 30 minutes to 7 hours, for chronic TTH - continuous headache); 2) the nature of HDN: compressive, constricting, squeezing, monotonous; localization of tension-type headache: diffuse, bilateral (one side may hurt more intensely); a typical description of TTH by patients: “the head was pulled together with a helmet, a hoop, a helmet, a hood”; 3) TTH does not worsen from habitual daily physical activity [7].

At the height of HDN, patients may experience the following accompanying symptoms: painful perception of sounds (phonophobia) or photophobia (photophobia), lack of appetite or nausea [7].

The main risk factors for tension-type headache are described by KE Waldie et al. (2014) using the example of 11-year-old patients [8].

Etiology and pathogenesis of HDN

V.V. Osipova (2010) points out that although initially TTH was considered as a predominantly psychogenic disorder, studies carried out over recent years have confirmed its neurobiological nature and the complex mechanism of development of this type of primary cephalgia [9]. Modern ideas about the pathogenesis of tension-type headache include the following main mechanisms: 1) mental stress (acute or chronic stress); 2) decreased pain threshold (including muscles and fascia); 3) insufficiency of the descending inhibitory pathways of the brain stem, which leads to tension in the pericranial muscles and headaches.

The emotional factor continues to be one of the most important in the etiology of episodic and chronic forms of tension-type headache (transient emotional experiences, chronic emotional stress). This is confirmed by the latest research performed by H. Kikuchi et al. (2015) [10]. Another significant reason is the factor of muscle tension, leading to the formation of muscular-tonic syndrome (painful tension in the muscles surrounding the head and neck) [2, 9]. Situations associated with prolonged or forced uncomfortable positioning of the head and neck lead to muscle tension. Thus, emotional stress is a factor that induces and maintains muscle tension, which, according to V.V. Osipova (2010), leads to the formation of a vicious circle “stress - muscle tension - pain” [9].

Repeated muscle tension in response to emotional stress causes reflex contraction and ischemia, which is accompanied by overexcitation of spinal neurons, increased sensitivity of pain muscle receptors and posture disorders. As a result, the cephalgic syndrome becomes even stronger. Schematically, the mechanism of formation of dysfunction of the pericranial muscles (muscular-tonic syndrome) can be represented as follows: reflex muscle tension → muscle ischemia → increased synthesis of algogens and sensitization of nociceptors → overexcitation of spinal neurons and postural disorders → dysfunction of the pericranial muscles.

Cervical muscular-tonic syndrome with tension-type headache leads to transient or permanent pain, as well as a feeling of tension and discomfort in the back of the head, the back of the neck and shoulder girdle, and facial muscles - most often the masticatory and temporal muscles (in addition to the headache itself) [9].

Treatment of tension-type headache

The leading role in the treatment of tension-type headache belongs to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Among them, the undisputed leader is ibuprofen (a derivative of phenylpropionic acid) [9, 10]. This drug, originally intended for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, subsequently took one of the leading places among NSAIDs used to achieve an analgesic effect. Currently, ibuprofen is used in more than 120 countries around the world, including Russia, where ibuprofen (for example, Nurofen) is most popular [9].

It is ibuprofen that is intended to relieve acute episodes of tension-type headache in patients of different ages [10–12]. This fact is emphasized by S. Derry et al. (2015) [13]. In some cases, in the treatment of acute attacks of tension-type headache, a combination of ibuprofen with benzodiazepines (diazepam, etizolam, etc.) is used [14, 15]. At the same time, one should remember the possibility of serious undesirable effects associated with the use of benzodiazepines [16].

In preventive therapy for tension-type headache, muscle relaxants (tolperisone, baclofen) and tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine, amitriptyline) are used. A certain role belongs to regime measures and diet therapy [17]. It is no coincidence that a number of publications in recent years report the role of “neurotrophic” factors in tension-type headache. This problem is addressed in the works of RB Domingues et al. (2015), as well as C. Folchini and P. A. Kowacs (2015) [18, 19]. The main neurodietological approaches for TTH include subsidies of magnesium, calcium, vitamin D, adequate water intake, and the use of medicinal herbs [17].

M. Woolhouse (2005) indicates that taking Mg preparations in relatively high doses (600 mg/day) for 12 weeks leads to a significant reduction in the frequency of tension-type headache (by 41.6%), as well as a significant reduction in the severity of cephalgic syndrome [20 ]. The use of calcium supplements may be justified due to the fact that vitamin D deficiency in patients with tension-type headache is accompanied by osteopenic conditions. S. Prakash et al. (2009, 2010) emphasize that vitamin D is effective in the treatment of tension-type headache in patients of different ages (usually prescribed in combination with calcium supplements) [21, 22]. Insufficient fluid intake is one of the possible causes of tension-type headache. Proper drinking regimen allows you to eliminate this etiological factor in HDN.

As mentioned above, medicinal herbs, as well as drugs based on them, are used in the treatment of tension-type headache. In particular, the following medicinal plants are relatively widely used: 1) chamomile (Matricaria recutita) - for muscle relaxation and stress reduction; 2) kava-kava (Piper methisticum) - to reduce the severity of cephalgic syndrome; 3) small periwinkle (Vinca minor LL.) - to improve cerebral oxygenation; 4) lobelia (Lobelia) - in order to achieve a sedative effect; 5) ginkgo biloba (Ginkgo biloba) - to improve cerebral hemodynamics [23].

Pharmacological drugs with venotonic action (Vinpocetine and Tanakan), widely used in our country, used for the treatment of tension-type headache (with concomitant venous insufficiency), are created on the basis of edible medicinal plants (respectively, a semi-synthetic derivative of devincan - an alkaloid of the plant Vinca minor LL. and extract ginkgo biloba plants, Ginkgo biloba) [3]. In turn, Y. Tong et al. (2015) emphasize the role of “Chinese herbal medicine” in the treatment of TTH [24].

Conclusion

Evidence-based medicine notes the role of NSAIDs (ibuprofen, etc.) in the treatment of tension-type headache in all age categories of patients [25]. Despite the variety of drugs used in the treatment of tension-type headache, the role of NSAIDs and, first of all, ibuprofen should be recognized as the leading one [26, 27]. Most other reported treatments for TTH are complementary or alternative.

In case of tension-type headache, representatives of NSAIDs (ibuprofen, etc.) not only act as drugs for the symptomatic treatment of this type of primary headache, but are also a means of etiopathogenetic therapy. NSAIDs have an effect on peripheral and central mechanisms of cephalalgia, including myofascial trigger zones and increased pericranial muscle tone.

Trigger points that cause the occurrence of tension-type headache are located in the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles, the posterior group of cervical muscles (suboccipital, etc.). Dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint (with the spread of pain to the temporal, parotid, occipital, cervicobrachial regions) and compression of blood vessels by the spasmodic muscle (ischemia, venous stagnation, accumulation of intermediate metabolism products) are of particular importance. It is also worth noting that a decrease in the concentration of β-endorphin in the cerebrospinal fluid during tension-type headache indicates a decrease in the activity of antinociceptive systems in the described pathology [28]. It is extremely important that ibuprofen has not only analgesic, but also anti-inflammatory effects. In particular, it inhibits COX-1 and COX-2, and also reduces the synthesis of prostaglandins; the anti-inflammatory effect of the drug ibuprofen is associated with a decrease in vascular permeability, improvement of microcirculation, decreased release of inflammatory mediators from cells, and suppression of energy supply to the inflammatory process [29]. This point takes on particular significance in light of the data presented by C. Della Vedova et al. (2013), who discovered a persistent increase in the main pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β in patients with chronic tension-type headache, indicating, in their opinion, the presence of the phenomenon of so-called “sterile neurovascular inflammation” in this type of pathology [30].

Ibuprofen is included in the List of Essential Medicines of the World Health Organization (2009), as well as in the List of vital and essential medicines approved by Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 2135-r dated December 30, 2009 [31, 32].

The drug Nurofen, presented in our country in various dosage forms, is highly effective in the treatment of tension-type headache.

Literature

- Jarvis S. Time to take tension-type headache seriously // Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 2015. 182: 1–2.

- Bendtsen L., Ashina S., Moore A., Steiner TJ Muscles and their role in episodic tension-type headache: implications for treatment // Eur. J. Pain. 2015. Jul. 6. doi: 10.1002/ejp.748. .

- Studenikin V.M., Goryunova A.V., Gribakin S.G., Zhurkova N.V. et al. Non-migraine cephalgia. In the book: New targets in pediatric neurodietology (collective monograph). Ch. 11 / Ed. Studenikina V. M. M.: Dynasty, 2012. P. 146–160.

- Voznesenskaya T. G. Second edition of the International Classification of Headache (2003) // Nevrol. magazine. 2004. No. 2: 52–58.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (HIS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) // Cephalalgia. 2013. 33(9): 629–808.

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). A short version based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases. M.: 2006. 741 p.

- Kropp P., Egli G., Sandor PS Tension-type headache introduction and diagnostic criteria // Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2010. 97: 355–358.

- Waldie KE, Thompson JM, Mia Y, Murphy R et al. Risk factors for migraine and tension-type headache in 11 year old children // J. Headache Pain. 2014. 15: 60.

- Osipova V.V. Tension headache: diagnosis and therapy. Bulletin of Family Medicine. 2010. No. 2: 26–30.

- Kikuchi H., Yoshiuchi K., Ando T., Yamamoto Y. Influence of psychological factors on acute exacerbation of tension-type headache: investigation by ecological momentary assessment. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015. 79 (3): 239–242.

- Studenikin V.M., Tursunkhuzhaeva S.Sh., Shelkovsky V.I. Ibuprofen and its use in pediatrics and child neurology // Issues. pract. ped. 2010. Vol. 5 (5): 140–144.

- Studenikin V.M., Tursunkhuzhaeva S.Sh., Shelkovsky V.I., Pak L.A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in pediatric practice // Attending Physician. 2011. No. 11: 82–84.

- Derry S., Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, Bendtsen L. Ibuprofen for acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache in adults // Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. 7: CD011474.

- Cvetkovic W., Strineka M., Knezevic-Pavlic M., Tumpic-Jakovic J., Lovrencic-Huzjzn A. Analysis of headache management in emergency room. Acta Clin. Croat. 2013. 52 (3): 281–288.

- Hirata K., Tatsumoto M., Araki N., Takeshima T., Igarashi H., Shibata K., Sakai F. Multi-center randomized control trial of etizolam plus NSAID combination for tension-type headache. Intern. Med. 2007. 46 (8): 467–472.

- Krishnan A., Silver N. Headache (chronic tension-type). BMJ Clin. Evid. 2009; 2009: 1205.

- Studenikin V.M., Pak L.A., Tursunkhuzhaeva S.Sh., Shelkovsky V.I. Diet for migraine and other types of headaches in children // Attending Physician. 2013. No. 1: 30–34.

- Domingues RB, Duarte H., Rocha NP, Teixeira AL Neurotrophic factors in tension-type headache // Arq. Neuropsychiatr. 2015. 73 (5): 420–424.

- Folchini C., Kowacs PA Neurotrophic factors and tension-type headache: another brick in the wall? //Arq. Neuropsychiatr. 2015. 73 (5): 377–380.

- Woolhouse M. Migraine and tension headache: a complementary and alternative medicine approach // Aust. Fam. Phys. 2005. 34 (8): 647–651.

- Prakash S., Shah ND Chronic tension-type headache with vitamin D deficiency: casual or causal association? //Headache. 2009. 49 (8): 1214–1222.

- Prakash S., Mehta NC, Dabni AS, Lakhani O. et al. The prevalence of headache may be related to the latitude: a possible role of vitamin D insufficiency? // J. Headache Pain. 2010. 11 (4): 301–307.

- Balch PA Headache: In: Prescription for nutritional healing. A practical A-to-Z reference to drug-free remedies using vitamins, minerals, herbs & food supplements. 4 th ed. New York: Avery. 2006; 455–460.

- Tong Y., Yu L., Sun Y. Chinese herbal therapy for chronic tension-type headache. Evid. Based Complement // Alternat. Med. 2015. 2015: 208492.

- Becker WJ, Findlay T, Moga C, Scott NA et al. Guideline for primary care management of headache in adults // Can. Fam. Physician. 2015. 61 (8): 670–679.

- Pierce CA, Voss B. Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children and adults: a meta-analysis and qualitative review // Ann. Pharmacother. 2010. 44 (3): 489–506.

- Southey ER, Soares-Weiser K., Kleijnen J. Systemic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in pediatric pain and fever // Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009. 25 (9): 2207–2222.

- Yakhno N. N., Parfenov V. A., Alekseev V. V. Headache (reference guide for doctors). M.: R-Doctor. 2000. 150 p.

- Morozova T. E., Rykova S. M. Ibuprofen in the practice of a general practitioner: possibilities for relieving pain syndromes // Treating Physician. 2013. No. 1: 75–79.

- Della Vedova C., Cathcart S., Donhalek A., Lee V., Hutchinson MR, Immink MA, Hayball J. Peripheral interleukin-1β levels are elevated in chronic tension-type headache patients // Pain Res. Manag. 2013. 18 (6): 301–306.

- WHO model list of essential medicines. 16th list. March 2009. 39 p. https://www.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html.

- Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 30, 2009 No. 2135-r. Moscow. List of vital and essential medicines. Russian newspaper. Federal issue. 2010. No. 5082.

V. M. Studenikin1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Economics Yu. S. Akoev, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

FSBI "NTsZD" Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Diagnostics

A neurologist can make a diagnosis of “cephalgic syndrome” after a comprehensive examination of the patient. Signs and symptoms of cephalalgia will help the doctor make a preliminary conclusion, so the patient should accurately describe the frequency, intensity and severity of pain.

To make a diagnosis, the patient is prescribed Dopplerography of the cerebral vessels, radiography or MRI of the neck - this allows one to immediately exclude or confirm the most common causes of cephalgic syndrome.

Principles of treatment

The drug Spazmalgon in the form of tablets is taken orally, the tablet is swallowed whole, without crushing or chewing, with a sufficient amount of water. If necessary, the tablet can be divided

How cephalalgia is treated depends on the reasons for its development. If the headache is associated with impaired cerebral circulation, antioxidant drugs, nootropics, and agents for normalizing vascular tone are prescribed.

Severe cephalgic syndrome in migraine is treated with drugs from the triptan group. The problem with migraine is that there is no universal treatment regimen. Some patients are helped to stop an attack by simple drugs like Spazmalgon, while most patients are forced to take sick leave during an attack, since even new generation drugs (triptans) do not help relieve an attack.

For tension headaches (vasomotor cephalgia), it is necessary to undergo a spinal examination. Quite often it is possible to overcome the problem with the help of mild sedatives and vitamins to normalize the activity of the nervous system (group B).

Moderate pain due to cephalgic syndrome due to osteochondrosis or after head injuries can be cured by using manual therapy, acupuncture, and taking antioxidants.

The treatment regimen depends on a number of factors and is selected by the doctor individually.

Chronic headache (cephalgia): symptoms and treatment

Cephalgia, or headache, is a nuisance that everyone has experienced at some point in their lives. This may be due to injury, overexertion, or hypertension. But the fact is that chronic cephalalgia (lasting for several days, for example) also occurs. Let's talk about this.

Symptoms

Of course, the manifestations of chronic cephalgia are countless, since there are also many ailments that constant headaches may indicate. For example, Dr. V.N. Shtok in 1987 proposed a division into the following types of chronic cephalalgia:

- Neuralgic;

- Vascular origin;

- Mixed;

- Muscle tension;

- Liquorodynamic;

- Psychalgia.

The development of medicine has made it possible to identify the following signs that you need to pay attention to first if a person experiences chronic headaches:

- Increasing power of cephalgia if you have to strain, sneeze or cough;

- Unexpected severe pain syndrome (possibly subarachnoid hemorrhage);

- Morning cephalalgia, and if nausea, vomiting and dizziness are also a sign, then we can judge the possible extensive course of the brain disease. As a rule, in this case, venous pressure may decrease;

- If a few days after the injury pain appears (subdural hematoma);

- Constant powerful cephalalgia for several hours, days, weeks may indicate a suspicion of a brain tumor, meningitis, encephalitis, but a possible illness is also chronic muscle pain, which can last more than 15 days a month or 180 days a year;

- If pain sensations that appear at night contribute to awakening from sleep (migraine, cluster headache).

Diagnostics

Diagnostics must be carried out by specialists in order to identify the ailment that torments the patient. The following methods are used for this:

- EchoEG (using this method, dilation of the ventricles in the brain is usually diagnosed);

- EEG (if there is a suspicion of migraine cephalgia);

- study of cerebral hemodynamics (blood circulation, blood vessels are diagnosed, signs of venous cephalgia can be seen);

- MRI, CT (to exclude tumors in the brain).

Therapy

Today there are 2 methods of therapy. The first involves prevention, the second - relieving the symptoms of a sudden attack (usually used in the treatment of migraines).

Preventive treatment consists of reducing the frequency, duration and severity of pain. This includes, depending on the pathology, types of therapy such as:

- Botulinum toxin (Botox injections);

- Antiepileptic drugs (Topiramate Gabapentin, Valproate);

- Venotonic drugs;

- Calcium antagonists;

- Ergotamine preparations;

- Cavinton cerebrovascular accident corrector;

- Sedatives (valerian, motherwort, mint, barbiturates);

- Antidepressants (Fluoxetine Amitriptyline);

- Central muscle relaxants (Mydocalm, Tizanidine);

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Aspirin, Ibuprofen, Diclofenac);

- Etc.

An important clarification: medications are not a guide to action, since certain medications are used in different cases. For venous pain, it is unacceptable to use calcium antagonists, and for vasomotor pain, venotonics. This should be taken into account. Treatment is prescribed by a doctor based on the diagnosis.

With the development of botulinum therapy, the effectiveness of botulinum toxin for chronic migraine has been proven. In the USA, operations have already been performed with Botox injection and removal of the trigeminal nerve, after which the patient’s migraine disappeared.

In addition, massage, physical therapy, and psychological therapy methods will be used.

Psychotherapy is effective if the patient has a disease that accompanies the disease, and also if the patient does not respond to drug treatment. Author: K.M.N., Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences M.A. Bobyr