Psychiatry Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy named after. P.B. Gannushkina No. 1 2004 Appendix

TO

At the turn of the millennium, sufficient evidence has accumulated indicating that epileptic discharge activity in functionally significant areas of the brain leads to permanent non-seizure disorders in patients with epilepsy in the form of behavioral, mental, and neuropsychological disorders.

With foci in the left hemisphere, changes in language and speech functions predominate, such as receptive and expressive aphasia, agraphia, acalculia, alexia, and speech dyspraxia. In right-hemispheric cases, the changes are complemented by auditory and visuospatial nonverbal agnosia, dyscopia, aprosody and disarticulation. Orbitofrontal, cingulate foci, involvement of nonspecific midline structures are accompanied by severe behavioral disorders, autism, mutism, aspontaneity, asociality, aggression, and eccentricity. Involvement of hippocampal structures and the amygdala is manifested by impairment of either socially motivated (left) or primary emotions (right) and specific verbal and nonverbal memory and learning [2–5, 8, 9, 11, 13, 27, 29]. The result of the generalization of these data was the introduction by the Working Group on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy into the draft of a new classification of epileptic syndromes of an extensive category of epileptic encephalopathies

[3, 7, 17, 19, 27, 43, 44]. This section of the classification includes epilepsies and epileptic syndromes, “in which epileptiform disorders lead to progressive brain dysfunction.” This, in particular, includes two syndromes: Landau-Kleffner epileptic aphasia and epilepsy with constant spike-wave complexes during slow-wave sleep, which in a significant number of cases occur without seizures at all and are clinically manifested only by severe speech impairment (in the first case) and progressive mental degradation (in the second), caused, according to modern concepts, by constant discharges of epileptiform activity in the brain, detected by electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography [6, 8, 9, 23, 28, 42]. In addition, in recent decades, dozens of observations have been published in which the main or only problem is not rare or absent seizures in the patient, but mental, communicative, cognitive, behavioral and social disorders associated with the picture of prolonged nonconvulsive status epilepticus or constant discharges of local or generalized epileptic activity in the EEG [2–8, 14, 16, 23, 25, 27, 32]. The coincidence of the localization of epileptic discharges in structures associated with impaired higher mental functions, the temporal connection between the appearance and disappearance of clinical disorders with epileptic activity, and the success of anticonvulsant therapy confirm the epileptic nature of these long-term nonconvulsive psychoneurological disorders [2–8, 10, 20, 24, 32–34 , 38]. By analogy with Landau–Kleffner acquired epileptic aphasia, cases of acquired epileptic frontal syndrome, an autistic, neuropsychological and behavioral disorder have been described [30, 31]. Based on the detection of epileptic discharges in the structures of the limbic-reticular complex in cases of schizophrenic, depressive and anxiety disorders resistant to psychotropic drugs, the concept of “psychotic epilepsy” was proposed [41]. These disorders constitute, according to the literature and our own estimates, depending on the form, from 5 to 40% of behavioral, mental and neuropsychological disorders [12, 28] and up to 3–10% of all epileptic disorders [7]. In all such cases, the reason for the patient or his parents to see a doctor is discommunicative, intellectual, pedagogical, psychotic, behavioral, and emotional disorders. The difficulties of correct diagnosis of such patients lie in the fact that at the time of treatment there are no special complaints about seizures, although in some cases (up to 50%), a special survey allows them to be identified in a long-term history [3, 7]. Since the complaints are not of a specific neurological nature, these patients are monitored and managed by psychiatrists (in cases of behavioral, mental, educational, social disorders) or defectologists (in cases of speech communication disorders). In the absence of seizures, the presence of epileptiform activity in the EEG in patients (if it is examined at all) is considered as an epiphenomenon that does not give rise to the prescription of antiepileptic drugs; patients are treated syndromologically without taking into account the pathogenetic mechanisms of the disorders and are often treated with psychostimulants, nootropics, psychotropic drugs, which causes failure treatment, and often worsening symptoms, since all these drugs reduce the threshold for convulsive readiness. Meanwhile, correct diagnosis and treatment of these disorders as epileptic allows 80% of such patients resistant to the mentioned therapy to obtain good improvement with the use of valproic acid (Depakine Chrono) and other antiepileptic drugs that suppress epileptic activity in the EEG [2, 3, 6– 8, 10, 17, 24, 26, 28, 32–34, 38].

1. Main clinical manifestations of non-convulsive epileptic encephalopathies with behavioral and mental disorders

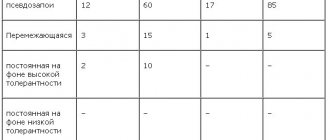

As already indicated, the disorders observed in epileptic encephalopathies represent almost the entire spectrum of symptoms of mental and behavioral disorders of ICD-10, as well as a wide range of syndromes of neuropsychological disorders, usually described within the framework of organic brain damage in neurological diseases. Accurate data determining the population representation of the discussed forms of psychoneurological disorders are currently not available. This is partly due to the novelty of the problem, but mainly due to the fact that publications devoted to it, and, accordingly, the clinical forms identified by the authors, as well as their rubrication, depend on the specialist’s profession. Thus, publications by neurologists and epileptologists mainly discuss neuropsychological disorders, classifying them as primary neurological pathologies, such as acquired epileptic aphasia, acquired epileptic visual agnosia, acquired epileptic frontal lobe syndrome [3, 6, 8, 14, 16, 18]. In publications by pediatricians and psychiatrists, the same disorders are interpreted as autism, pervasive developmental disorders, school skills disorders, etc. [7, 10, 12, 24, 25, 28, 37]. On the other hand, hyperkinetic disorders such as tics (Tourette's syndrome), being a primary psychiatric diagnostic entity, are in most cases treated by neurologists. Thus, it should be recognized that this entire group of disorders is a general psychoneurological one, but the largest number of such patients is found in pediatric institutions providing assistance to children with behavioral and mental disorders. The difficulties in assessing the relative frequency of various manifestations of nonconvulsive encephalopathies are also determined by the fact that, as a rule, they occur in complex combinations and the diagnosis is made according to the main disorder corresponding to the profile of the specialist to whom the patient is seen. According to our observations, in child psychiatry departments, the most common forms of disorders are socialized and unsocialized behavior disorders and disorders of school skills, causing oppositional disorder (about 30%), hyperkinetic disorders (about 30%), attention deficit, general developmental delay (about 20). %); Less common (about 3–5%) are the diagnoses of “autism,” “Asperger’s syndrome,” and “selective mutism” [7, 10]. At the same time, in the same populations, there are numerous cases of neuropsychological speech disorders, interpreted as a general delay in speech development with various forms of speech disorders in the form of dysphasia, expressive aphasia, speech dyspraxia, often interpreted as stuttering, agrammatism, dyslexia, verbal memory disorders, dysarthria , dyslalia. These disorders are sometimes combined with orolingual incoordination, drooling and, as a rule, are combined with each other [5]. In neurological publications, diagnoses of neuropsychological disorders account for up to 60% and include Landau-Kleffner epileptic acquired aphasia syndrome (about 20%), epileptic encephalopathy with persistent spike-wave complexes in slow-wave sleep, acquired frontal lobe syndrome, acquired visual agnosia, speech dyspraxia [ 2, 3, 9, 8]. Particular manifestations of the listed syndromes include dyslexia, disorders of processing sequential information, deficits in visuospatial skills, and acoustic agnosia [39]. Although epileptic encephalopathies are described mainly as disorders of childhood, they can also occur in adulthood, according to some data - after 17-20 years, in some cases - older. Developing for the first time in adulthood, disorders associated with epileptic encephalopathy manifest themselves as schizophrenic, affective and anxiety disorders, sometimes complicated by addiction disorders [2, 3, 35, 40, 41, 45]. Complaints about neurological disorders proper (in addition to neuropsychological disorders) in the sensorimotor sphere caused by epileptic dysfunction are usually absent in non-convulsive epileptic encephalopathies with behavioral and mental symptoms. The most typical general asthenic complaints are fatigue, decreased performance and perseverance, increased nervousness, episodic tension headaches, and parasomnias are also noted. Anamnestic data and hereditary factors include pregnancy pathology, impaired gestation, perinatal pathology, parental alcoholism, parental mental illness, epilepsy in relatives, a history of febrile convulsions, and mild traumatic brain injury. An objective examination usually reveals subclinical signs of reflex hemisyndrome without pathological signs, weak signs of oral automatism, Chvostek’s symptom, increased deep reflexes, and muscle hypotonia.

2. Electroencephalographic and other paraclinical manifestations of non-convulsive epileptic encephalopathies with behavioral and mental disorders

Certain patterns have been identified in the manifestation of different types of epileptiform activity in the EEG.

Generalized bilateral synchronous discharges

of spike-wave activity caused by the involvement of the nuclei of the nonspecific activating reticular formation and the mediobasal structures of the frontal lobes, patterns of typical and atypical absences or their statuses are manifested by dysfunction of tracking, directed attention, short-term memory, consciousness, goal-directed behavior, attention, function conscious contact, learning ability.

In a milder form, these epileptic disturbances in the EEG are manifested by moderate confusion, disorientation, some slowness of reaction, a feeling of strangeness, sometimes lasting up to several days [29]. Such mild disorders associated with episodic discharges of generalized bilaterally synchronous discharges in the EEG, usually regarded as “subclinical,” are called “transient cognitive impairment.” It has been shown that they may underlie serious disorders of learning, development and behavior in children with epilepsy, and the degree of these permanent disorders correlates with the frequency and intensity of epileptic electrogenesis in the EEG [9, 11, 13, 33, 37]. Bilaterally synchronous epileptiform discharges in the frontal leads are caused by epileptic activity in the cingulate gyrus and orbitofrontal cortex and are accordingly accompanied by severe frontal dysfunction with disorders of socially motivated behavior, aggression, autism, and mutism [7, 25, 31]. If EEG data is underreported, such clinical disorders are regarded in children and adolescents as general learning and behavioral disorders, oligophrenia [37]. In older patients, patterns of absence status involving nonspecific midline structures are manifested by disturbances in holistic thinking with psychiatric symptoms. So, back in 1949 H. Wycis et al. using long-term stereotactic recordings showed that in some patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who have never had epileptic seizures, paranoid symptoms are directly related to epileptic discharges recorded in the mediobasal structures of the brain with normal convexital EEG [45]. The presence of patterns of generalized epileptiform activity, indicating dysfunction of the midline and mediobasal structures of the brain in disorders interpreted as schizophrenia or depression, was also shown in later studies [2, 35, 40, 41]. Focal epileptiform changes in the EEG

are manifested by dysfunctions associated with the corresponding localization. In Landau–Kleffner epileptic aphasia, epileptiform discharges are recorded in the temporal leads. With left-sided localization of discharges, amnestic, sensory and motor aphasia is noted. In right-sided cases, auditory agnosia, disarticulation, and speech dyspraxia may be observed [3, 7, 8, 16, 36, 39]. In extreme severity, these disorders create a picture of mutism, which, if misdiagnosed, is interpreted as deaf-muteness, which leads to attempts to teach patients sign language and, in the absence of treatment for epileptic dysfunction, to lifelong loss of speech [2, 6, 20]. Centrotemporal spikes are accompanied by speech dyspraxia, up to mutism, dyslexia, agrammatism, and disorders of serial information processing. If centrotemporal spikes are combined with a pattern of constant spike-wave complexes in slow-wave sleep, severe general mental retardation is associated with this [3, 5, 7, 8, 16, 18, 23, 31, 34, 36, 39]. Occipitolobar epileptic discharges manifest themselves along with other disorders in visuospatial agnosia [7, 18]. Frontal-lobar discharges of epileptiform activity are manifested by schizoaffective disorders, dysfunction of socialization, the ability to plan behavior, and aggression [2–6, 25, 31]. In addition to this gross epileptiform activity, epileptic encephalopathies can be accompanied by a general slowdown in electrical activity, disturbances in topical differentiation, excessive synchronization in the theta and delta range, bilaterally synchronous bursts of delta, theta and alpha activity, which, due to the extremely high amplitude ( up to 1000 μV or more) acquire an acute form and, accordingly, an epileptiform character [10, 19]. Considering the critical role of identifying epileptiform activity for the correct therapeutic approach in the group of pathologies under discussion, if it is suspected, a thorough EEG examination is necessary using all the necessary functional tests, and in the absence of obvious data in the daytime recording, a sleep EEG study, since in Landau-Kleffner epileptic aphasia epileptiform activity can be detected during the transition from the first to the second stage of sleep and beyond. It should be noted that the clinical phenomena of epileptic encephalopathy can occur with epileptic foci in the mediobasal regions of the temporal and frontal lobes, which are not manifested in the scalp EEG. Magnetoencephalography is used to diagnose such disorders.

3. Pharmacotherapy of non-convulsive epileptic encephalopathies

Thus, over the past two decades, independent research in related fields of medicine - neurology, epileptology, psychiatry and pediatrics - has led to the identification of almost the same group of pathologies, characterized by the presence of severe permanent brain dysfunction, manifested by behavioral, mental and neuropsychological disorders without actual epileptic seizures, combined with persistent epileptiform activity in the EEG. It is the abnormal “epileptic” hypersynchronous activity of neurons in functionally significant parts of the brain that leads to disruption of the corresponding mental function. The relative rarity of their descriptions is explained by the fact that these cases fall on the divide between psychiatry and neurology. A patient with dominant mental complaints is immediately referred to a psychiatrist, who, as a rule, begins symptomatic treatment with psychotropic drugs and nootropics, without paying due attention to EEG data, to which in most cases the patient is not even referred, and in the absence of seizures, even in the presence of epileptiform activity the patient is not prescribed antiepileptic drugs, and the disorder is not considered a form of epileptic disease. It is interesting to note that, working in neurological institutions, we collected a little more than a dozen of the analyzed observations over a period of about 20 years. Work in pediatric psychiatric institutions for only 4 years yielded about a hundred additional cases [2–8, 10]. It is obvious that such patients end up in neurological institutions only by chance, and in the absence of a neurologist with in-depth specialization in EEG and epileptology in a psychiatric institution, these cases are not diagnosed and, accordingly, are treated incorrectly: such patients receive antipsychotics, antidepressants, nootropics, psychostimulants. These drugs lower the seizure threshold and often lead to worsening symptoms. Carbamazepine, prescribed in some cases as a behavior corrector, can also worsen the condition of these patients, in particular, leading to the appearance of “electrical status epilepticus in slow-wave sleep” [2, 9, 22]. As follows from the above, treatment of mental, behavioral and cognitive, neuropsychological disorders caused by epileptic encephalopathy should be aimed at suppressing epileptiform activity in the EEG, since it is epileptic discharges in the brain that cause disruption of higher functions, manifested by corresponding psychopathology. Therefore, the choice of drug should be focused specifically on its effectiveness in suppressing epileptiform activity, and, in addition, it is desirable that it itself has a positive psychocognitive effect and does not give negative side effects in this regard. It should be said that some anticonvulsants in a certain percentage of cases enhance epileptiform activity, and sometimes lead to the appearance or worsening of epileptic seizures. This is characteristic of carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and of the newest drugs – lamotrigine, topiramate, vigabatrin [21, 22]. In addition, these drugs in some cases aggravate mental and behavioral symptoms [6, 21, 22]. The only drug that has been proven to effectively suppress epileptiform activity in the EEG is valproic acid [1–3]. Its second important property is that it almost never causes the appearance, frequency or severity of epileptic seizures [2, 3, 22]. That is why in the overwhelming majority of publications devoted to the treatment of epileptic nonconvulsive encephalopathies, valproic acid is used and recommended for use as the drug of first choice [1–8, 10, 12, 17, 24, 32, 33]. In our studies, which to date have included more than 50 patients who were observed for at least a year, improvement to one degree or another was obtained in all, and in 70% of cases practical recovery was achieved [3, 7, 10]. Particularly indicative is the study by S.I. Shevelchinsky et al. (2004), who compared two groups of patients with behavioral disorders, similar in all respects, one of which was treated with antipsychotics, and the other with Depakine Chrono. The results were assessed quantitatively based on the results of pathopsychological and neuropsychological testing and the dynamics of pathological activity in the EEG during treatment. For most indicators, patients treated with Depakine Chrono showed a statistically significant improvement, while treatment with neuroleptics was either ineffective or caused deterioration in the same indicators [10]. It is as a drug with the best combination of effectiveness and safety that valproate is recommended in special works devoted to the treatment of epileptic encephalopathies, including non-convulsive ones [17]. The use of the Depakine Chrono form is also motivated by the fact that in maintaining normal cognitive processes, the most important role belongs to the continuity of the psyche, as well as the normal flow of information processes in slow-wave sleep. Both of these aspects are disrupted by epileptiform discharges, which are activated when the concentration of the drug in the blood decreases. It is the property of depakine chrono to maintain a stable concentration throughout the day that is a factor in its particular effectiveness in the treatment of epileptic encephalopathies [1, 2]. Next, we summarize the main properties of Depakine Chrono, which determine its primary choice for epileptic encephalopathies.

Rationale for the use of depakine chrono as a first-choice drug for epileptic encephalopathies

1. The absence of contraindications and the risk of worsening symptoms and the addition of other disorders, due to the following clinical and pharmacological features of Depakine compared to alternative drugs: a) Depakine Chrono does not cause sedation, motor stiffness, agitation, dyskinesias and other psychomotor phenomena inherent in antipsychotics, tranquilizers, psychostimulants, antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs; b) depakine chrono effectively suppresses epileptiform activity, in contrast to neuroleptics, which lower the threshold of convulsive readiness, and carbamazepine, which often increases epileptiform activity in the EEG with aggravation of psychiatric symptoms and possible provocation of seizures [2, 6]; c) depakine chrono eliminates the risk of developing iatrogenic late dystonia, dyskinesia, parkinsonian syndrome, possible with the use of neuroleptics and, accordingly, does not require the use of correctors; e) depakine does not cause dependence and tolerance of symptoms to the drug due to a decrease in the sensitivity of neuronal receptors. 2. In addition to the antiepileptic effect, valproic acid has its own antipsychotic effect, independent of the anticonvulsant effect, and is used regardless of epilepsy as an antipsychotic drug, behavior corrector, anxiolytic for mood disorders, addiction diseases, emotional disorders, making up, for example, 35% of all drugs used in psychiatric clinics in the USA [15]. 3. Valproic acid is a neuroprotector and protects neurons from excitotoxic death, characteristic of a number of neurological, epileptic and psychiatric diseases and thereby prevents the progression of the disease, and in some cases contributes to its interruption and practical recovery [2, 6]. 4. Valproic acid promotes the differentiation of neuroblasts and the proliferation of dendrites, thereby promoting the maturation of the functional systems of the brain [6]. 5. Effective suppression of epileptic activity in the EEG by valproic acid makes it possible, already on the 3rd–5th day of a stabilized therapeutic dose, to verify, using EEG control, the correct choice of the drug, predict success in a given patient, and subsequently monitor the success of treatment using the dynamics of EEG changes [1 –6]. 6. Treatment with valproic acid in most cases does not produce adverse side effects from the central nervous system, and if they occur, they are not long-term and are completely reversible when the drug is discontinued or its dose is reduced [2, 3, 12, 15]. It should be noted that, in contrast to epileptic seizures, which require treatment for at least 2 years, and sometimes for life, treatment with depakine for chronic non-convulsive epileptic cognitive disorders under EEG and clinical control is carried out only for the time necessary to stabilize the achieved clinical effect. Our experience suggests that, provided that epileptiform activity in the EEG is successfully completely suppressed under the influence of depakine chrono, the required duration of treatment in most cases ranges from 6 months to 2-3 years. If unsuccessful, other antiepileptic drugs are used that suppress epileptiform activity in the EEG (topiramate, lamotrigine) [26]. If ineffective in cases of severe speech disorders associated with Landau-Kleffner syndromes and “electrical status in slow-wave sleep,” steroids are used, and if pharmacotherapy is ineffective, surgical treatment is used [20, 38]. This aggressiveness of therapy emphasizes the critical role of epileptic activity in the EEG in the development of behavioral, mental and cognitive disorders.

Possible side effects

Carbamazepine tablets usually do not cause unwanted reactions, however, like all medicines, they can sometimes cause side effects.

Some side effects may be serious

If any of the following adverse reactions develop after taking the drug, you should immediately stop taking them and consult a doctor:

- Serious skin reactions: rash, redness of the skin, blistering of the lips, eyes or mouth, peeling skin accompanied by fever. These adverse reactions are most likely to occur in people of Han (Chinese) and Thai descent.

- Mouth ulcers or unexplained bruising or bruising

- Sore throat and/or high fever

- Yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes

- Swelling of the ankles, feet, or legs

- Any signs of nervous disorders or confusion

- Joint and muscle pain, rash on the bridge of the nose and cheeks, and breathing problems (these may be a sign of a rare side effect called lupus erythematosus)

- Fever, skin rash, joint pain, abnormal blood tests and liver function (these phenomena may be a sign of hypersensitivity with multiple organ damage)

- Bronchospasm with wheezing and cough, difficulty breathing, weakness, rash, itching or swelling of the face (these reactions may be a sign of a severe allergic reaction)

- Pain in the stomach

The following adverse reactions have also been reported

Very common: (≥1/10)

Leukopenia (decreased number of white blood cells, which are necessary to protect the body from infections); dizziness and increased fatigue; feeling unsteady or having difficulty controlling movements; nausea or vomiting; changes in liver enzyme levels (usually without any symptoms); skin reactions, which can be quite serious).

Frequent: (from ≥1/100 to <1/10)

changes in your blood, including an increased tendency to bruise or bleed; fluid retention and swelling; weight gain; decreased sodium levels in the blood, which may cause confusion; headache; double vision or blurred vision; dry mouth.

Uncommon (≥1/1000 to <1/100)

Abnormal involuntary movements, including tremors or tics; abnormal eye movements; diarrhea; constipation

Rare (≥1/10000 to <1/1000)

Damage to the lymph glands; folic acid deficiency; generalized allergic reactions, including rash, joint pain, fever, problems with the kidneys and other organs; hallucinations, depression; loss of appetite; anxiety; aggression; agitation; confusion; speech disorder; numbness or tingling in the arms and legs; muscle weakness; high blood pressure (which can cause dizziness and facial flushing, headaches, fatigue and nervousness); low blood pressure (symptoms: feeling weak, light-headed, dizzy, confused, blurred vision); heart rhythm disturbances; stomach ache; liver damage, including jaundice; lupus symptoms.

Very rare (≥1/100,000 to <1/10,000)

Changes in blood composition, including anemia; porphyria; meningitis; swelling of the mammary glands and milk production, which occurs in both men and women; abnormalities in thyroid analysis; osteomalacia (pain when walking and curvature of the long bones of the legs); osteoporosis; increased levels of lipids in the blood; taste disturbances; conjunctivitis; glaucoma; cataract; hearing impairment; cardiovascular problems, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT), the symptoms of which may include fatigue, pain, swelling, fever, changes in skin color and visibility of superficial veins; pulmonary and respiratory problems; serious skin reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (these reactions may occur more frequently in patients of Thai or Chinese descent); ulcers in the mouth and tongue; liver failure; increased skin sensitivity to sunlight; changes in skin pigmentation; acne; increased sweating; hair loss; excess hair growth on the face and body; muscle pain or cramps; sexual problems that may further affect male fertility, loss of libido or impotence; renal failure; drops of blood in the urine, frequent/infrequent or difficult urination.

The following symptoms have also been reported, but their frequency cannot be estimated from the available data:

Serious skin reactions accompanied by feeling unwell and changes in blood test results. Diarrhea, abdominal pain and fever (signs of colon inflammation), recurrence of herpes infection (may be important if the immune system is weakened), complete loss of nails, fractures, decreased bone density, drowsiness, memory loss, purple or red purple bumps that may cause itching.

There is no need to worry about these side effects. Most people taking carbamazepine do not experience the reactions described.

If any of the symptoms bother you or you notice a side effect not listed in this leaflet, please consult your doctor.

Your doctor will choose the most optimal treatment for you and may prescribe a different drug.

Symptoms of bone disorders have also been reported, including osteomalacia and osteoporosis (thinning of the bones) and fractures. Check with your doctor or pharmacist if you are on long-term treatment with antiepileptic drugs, have had symptoms of osteoporosis, or have taken steroid medications.

Side Effect Reporting:

Tell your doctor or pharmacist if you notice any side effects, including any side effects not listed in this leaflet. You can also report side effects to , by going to the website www.arpimed.com and filling out the appropriate form “Report a side effect or ineffectiveness of a drug” or directly to the Scientific Center for Expertise of Medicines and Medical Technologies named after Academician E. Gabrielyan, going to website: www.pharm.am to the section “Report a side effect of a drug” and fill out the form “Card for reporting a side effect of a drug” Hotline phone: +37410237665; +37498773368. By reporting side effects, you can help provide more information about the safety of this drug.

How to store Carbamazepine

- Store out of reach of children, protected from moisture and light at a temperature of 15-250C

- Do not take Carbamazepine after the expiration date indicated on the drug package. When indicating the expiration date, we mean the last day of the specified month

- Shelf life - 3 years

Medicines should not be disposed of in wastewater or sewer systems. Ask your pharmacist how to dispose of any medicine you no longer need. These measures are aimed at protecting the environment.

Package contents and additional information

What Carbamazepine contains

Active substance: carbamazepine – 200 mg per tablet;

Other components: microcrystalline cellulose, sodium carmellose, magnesium stearate, Aerosil 200

What Carbamazepine looks like and contents of the pack

Round biconvex tablets of white or almost white color with a score on one side; without smell

Description of packaging

Cardboard packaging containing 50 tablets in strip packaging (PVC/aluminium)

5 blister packs of 10 tablets each, together with an insert, are placed in a cardboard package.

Cardboard packaging containing 40 tablets in a blister pack (PVC/aluminum).

4 blister packs of 10 tablets each, together with the package insert, are placed in a cardboard package.

Vacation conditions

Dispensed by prescription.