Dysphagia refers to pathologies of the esophagus and larynx. With this condition, swallowing liquids and food is difficult or impossible. The causes may include both disturbances in the functioning of various organs and diseases of a neuralgic nature. To make a diagnosis, a thorough examination is necessary, and therapeutic measures are selected individually for each patient.

Pathology cannot be left without attention, since it is impossible to do without the help of doctors. Doctors at the 24-hour Yusupov Hospital specialize in this pathology and successfully cope with dysphagia of any severity.

Causes of dysphagia

The disease can occur against the background of both genetic and acquired pathologies. The most common cause of dysphagia is pathological processes in the esophagus, oropharyngeal cavity, heart and brain. Experts include the following common factors that cause the disease:

- Malignant or benign neoplasms in the oropharynx (tumors);

- Inflammatory diseases of the esophagus and its mucous membrane;

- Cancer of the esophagus or stomach;

- Purulent-inflammatory processes in the oropharynx (sore throat, abscess, etc.);

- Diverticula of the esophagus (protrusion of its walls);

- Complete or incomplete paralysis of the pharyngeal muscles;

- Various injuries of the esophagus (knife and bullet wounds);

- Injuries due to sharp foreign objects entering the esophagus;

- Quincke's edema due to severe allergies;

- Enlarged heart after coronary artery disease, heart attack, heart failure;

- A chronic disease accompanied by the reflux of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus;

- Atherosclerotic lesion of the vascular system of the brain;

- Narrowing of the esophagus of various etiologies;

- Multiple system atrophy (death of certain groups of nerve cells);

- Aortic aneurysm (protrusion of the wall of a certain area of the aorta);

- Acute renal or liver failure;

- Severe diseases of the muscles, vascular system and skin (dermatomyositis);

- Injuries to the brain or cervical spine;

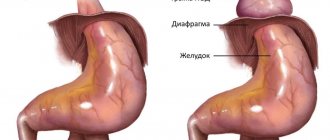

- Hiatal hernia;

- Severe hypertension (with damage to target organs);

- Cerebrovascular accidents;

- Systemic lupus erythematosus, affecting the kidneys, musculoskeletal system and other organs;

- Varicose veins in the esophagus;

- Chemical burns of the esophagus (acid, alkali);

- Systemic scleroderma (autoimmune connective tissue disease).

Dysphagia is often caused by a severe toxic infectious disease (botulism), Parkinson's disease (shaking paralysis), encephalitis and neuromuscular diseases (polymyositis, myasthenia gravis and others). In childhood, dysphagia most often occurs with cerebral palsy (cerebral palsy).

Each disease is assigned a code according to ICD 10 (International Classification of Diseases). Dysphagia is coded R13 and refers to pathologies associated with difficulty swallowing.

A high risk group includes children with paralysis of four limbs, athetosis (convulsions), congenital pathologies of the brain, esophagus and pharynx, as well as elderly people with severe chronic diseases.

Classification

Pathology varies depending on the location of the lesions, type and severity. In medical practice, the classification of dysphagia is as follows:

By location

- Oropharyngeal (oropharyngeal) - divided into oral, pharyngeal and cricopharyngeal dysphagia. The lesions are localized in the oropharynx area. The bolus of food moves from the pharynx to the esophagus with difficulty. When trying to swallow, the patient may choke, and the contents may enter the nasal cavity or trachea. Oropharyngeal dysphagia occurs due to a disorder of the neuromuscular connection.

- Esophageal - affects the distal (lower) zone of the esophagus, and difficulty swallowing occurs in the cervical region. Symptoms are similar to the oropharyngeal form. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis can only be determined by a doctor during an examination of the patient.

- Cricopharyngeal incoordination - with this disease, the contraction of certain fibers is impaired, which leads to problems with relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle. This often causes protrusion of the walls of the esophagus and the development of pathological processes in the lungs.

By appearance

- Paradoxical - characterized by difficulty swallowing, while solid food passes better than liquid food. Most often occurs against the background of diseases of the esophagus. With tumor neoplasms, patients first refuse solid food, then cereals and soups, and then drinks. Sometimes paradoxical dysphagia weakens or even disappears, but the stage of false remission is short-lived. After some time, the disease makes itself felt again.

- Sideropenic is a dystrophic change in the mucous membranes of the esophagus. Most often this is a consequence of iron and nutrient deficiency in the human body. Is genetic or acquired. Lack of iron causes a disruption in the production of oxidative elements, which leads to pathologies of the muscles responsible for swallowing.

- Neurogenic - caused by a disorder of the nervous system and is characterized by difficult formation of a food bolus in the oral cavity or obstruction of food through the esophagus. The most common factors causing neurogenic dysphagia are major ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke and serious traumatic brain injury.

- Psychogenic - when pathology occurs while eating, the patient feels a “lump” in the throat or pain in the chest area. In addition to impaired swallowing functions, severe heartburn is noted. The cause of the pathological condition is frequent stress and nervous strain.

Due to the occurrence

- Functional - also called nervous dysphagia. Frequent causes of occurrence are a disorder of the esophagus, which was the result of a severe disorder of the nervous system. With pathology, the patient has difficulty swallowing food, and breathing is often impaired. In childhood, the disease is accompanied by loss of appetite, sleep disturbances and vomiting.

- Organic - a consequence of various diseases that contribute to damage to the oropharynx or esophagus.

In addition, dysphagia is also divided according to the form of its course - progressive and chronic. In the second case, the symptoms weaken from time to time and occur during an exacerbation of the pathological process. The chronic form is diagnosed due to complications of the progressive one.

Dysphagia / World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO). Practical guide. 2004.

Dysphagia

OMGE Practical Guide

January 2004: final version

Authors of the review

- JR Malagelada

- F. Bazzoli

- A. Elewaut

- M. Fried

- JH Krabshuis

- G. Lindferg

- P. Malfertheiner

- G. Sharma

- N. Vakil

1. Definition

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty in a person at the beginning of swallowing (usually defined as oropharyngeal dysphagia), or as a feeling that there is an obstruction in the passage of food or liquid from the mouth to the stomach (usually defined as esophageal dysphagia).

Dysphagia is thus the sensation of an obstruction to the normal passage of ingested food.

2. Introduction and main points

Swallowing is a process that is regulated by the swallowing center located in the medulla oblongata, and in the middle and distal part of the esophagus by a powerful autonomic peristaltic reflex, which is coordinated by the enteric nervous system located in the wall of the esophagus. The figure below shows the physiological mechanisms involved in the different phases of swallowing.

Phases of swallowing stages

| Oral phase |

| Oropharyngeal phase |

| Esophageal phase |

A conclusion about the localization of dysphagia should be made based on the patient’s complaints; the lesion will be located either in the place indicated by the patient’s sensations, or below the specified location.

It is equally important to find out after taking what food (solid, liquid or both) dysphagia occurs, whether it is constant or intermittent. Determining the duration of symptoms is also important.

Although they can often occur together, it is important to rule out odynophagia (painful swallowing). Finally, differential diagnosis based on the identification and analysis of symptoms should exclude the presence of Globus hystericus (sensation of a lump in the throat), chest compression, difficulty breathing and phagophobia (fear of swallowing).

Key points to consider in the medical history:

- Localization

- Nature of food and/or liquid

- Persistence or intermittency of symptoms

- Duration of symptoms

Supporting points: is dysphagia oropharyngeal or esophageal? This conclusion can be made with confidence on the basis of a very thorough examination, which makes it possible to accurately assess the type of dysphagia (oropharyngeal dysphagia compared to esophageal dysphagia occurs in 80 - 85% of cases).

2.1 Oropharyngeal dysphagia - main manifestations

Oropharyngeal dysphagia may also be called "high" dysphagia if it involves the oral cavity or pharynx.

Patients have difficulty at the beginning of swallowing and they usually point to the cervical region as the location of this difficulty.

The following accompanying symptoms:

- Difficulty starting to swallow

- Nasal regurgitation

- Cough

- Nasal speech

- Weakened cough reflex

- Choking attack

- Dysarthria or diplopia (may accompany neurological disorders that cause oropharyngeal dysphagia)

- Halitosis may occur in patients with large Zenker's diverticulum containing residual food debris, as well as in patients with progressive achalasia or long-term obstruction of the lumen, leading to the accumulation of decomposing food.

An accurate diagnosis can be established after the neurological disorders accompanying oropharyngeal dysphagia are identified, these may be:

- Hemiparesis resulting from stroke

- Ptosis of the eyelids

- Signs of myasthenia gravis in pregnant women (weakness towards the end of the day)

- Parkinson's disease

- Other neurological diseases, including cervical dystonia, cervical hyperostosis, Arnold-Chiari malformation (caudal displacement of the brain and entrapment in the foramen magnum)

- Identifying a specific decrease in the number of brain nerves involved in the regulation of swallowing may also help to accurately determine the cause of oropharyngeal disorders at diagnosis.

2.2 Esophageal dysphagia - main manifestations

Esophageal dysphagia may be called "lower" dysphagia because it is predominantly located in the distal esophagus, although it should be noted that some patients with esophageal dysphagia such as achalasia may complain of difficulty swallowing in the cervical esophagus, which mimics oropharyngeal dysphagia. .

- Dysphagia, which occurs equally after ingestion of solid and liquid foods, often raises suspicion for the presence of esophageal movement disorders. This suspicion is heightened in cases where intermittent dysphagia when eating both solid and liquid foods is accompanied by chest pain.

- Dysphagia, which occurs only with solids and never with liquids, suggests the possibility of mechanical obstruction with luminal stenosis <15 mm. If the disease progresses, the possibility of developing peptic stricture or carcinoma must be taken into account. It should be borne in mind that patients with peptic stricture have long-term heartburn, but never lose weight. In contrast, patients with esophageal cancer are older people with significant weight loss.

Physical examination of patients with esophageal dysphagia is usually of limited value, although cervical/supraclavicular lymphadenopathy may be identified in patients with esophageal cancer. In addition, some patients with scleroderma and secondary peptic strictures may have CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud's disease, impaired esophageal motility, sclerodactyly, the presence of telangiectasia).

Bad breath may suggest the presence of achalasia or long-standing obstruction with the accumulation of slowly decomposing food debris in the lumen of the esophagus.

3. Disease severity and epidemiology

Dysphagia is common. For example, cases of dysphagia during emergency medical care can reach a high figure of 33%, and analysis of data on home care shows that 30 - 40% of patients have swallowing disorders, which lead to a large number of aspiration complications.

On the other hand, epidemiological data cannot provide a global view because the number of underlying diseases that can cause dysphagia varies significantly between Western Europe, North America, South Asia, and the Middle East and Africa. In addition, the incidence of disease varies greatly depending on the age of the patients. It should also be remembered that the spectrum of disorders in dysphagia in children differs from that in older people. Thus, only approximation is possible on a global scale. Dysphagia typically occurs at any age, but the prevalence increases with age.

In young patients, dysphagia often accompanies head and neck diseases, as well as cancer of the throat and oral cavity. The incidence of tumors varies among countries. For example, while adenocarcinoma is the predominant type of esophageal cancer in the United States, squamous cell carcinoma predominates in India and China. Likewise, corrosive esophageal stricture (in individuals who have taken corrosive agents for suicidal purposes) and tuberculosis may also be important causes of dysphagia in non-Western countries.

4. Causes of dysphagia

In order to establish the etiology of dysphagia, it is useful to follow the classification that is intended to evaluate symptoms, i.e. a classification that allows us to identify differences between diseases that most often affect the pharynx and proximal esophagus (oropharyngeal or “upper” dysphagia) and diseases that most often affect the body of the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction (esophageal or “lower” dysphagia). However, it should be kept in mind that many disorders overlap and can be the cause of both oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia. A thorough medical history, including evaluation of treatment, is important because medications may be involved in the pathogenesis of dysphagia.

4.1 Oropharyngeal dysphagia

In young patients, oropharyngeal dysphagia most often occurs due to inflammatory muscle diseases, the presence of membranes and ring-shaped formations. In older people, this type of dysphagia is most often caused by central nervous system disorders, including stroke, Parkinson's disease and dementia. Typically, a distinction must be made between mechanical problems and neuromuscular contractility disorders, as outlined below.

4.1.1. Mechanical and obstructive causes

- Infections (including retroperitoneal abscesses)

- Thyromegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Zenker's diverticulum (if a small diverticulum is present, the cause may be dysfunction of the upper esophageal sphincter)

- Decreased muscle extensibility (myositis, fibrosis)

- Malignant lesions of the head and neck

- Cervical osteophytes (rare)

- Oropharyngeal malignancy and neoplasms (rare)

4.1.2. Neuromuscular disorders

- Central nervous system diseases such as stroke

- Contractile disorders such as cricopharyngeal spasm (upper esophageal sphincter dysfunction) or myasthenia gravis of pregnancy, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, etc.

Post-stroke dysphagia is detected in almost 50% of cases. The severity of dysphagia correlates closely with the severity of stroke. 50% of patients with Parkinson's disease exhibit a number of symptoms consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia, and in almost 95% of the disorders are detected during video esophagography. Clinically significant dysphagia can be detected in the early stages of Parkinson's disease, but much more often in the later stages.

4.1.3. Other reasons

- Incorrect position of teeth

- Mouth ulcers

- Xerostomia

- Long-term use of penicillamine

4.2. Esophageal dysphagia

The most common causes of dysphagia are three types:

- Damage to the mucosa, which leads to narrowing of the lumen due to inflammation, fibrosis or tumor growth

- Diseases of the mediastinum that lead to obstruction of the esophagus by direct invasion or by enlarged lymph nodes

- Neuromuscular diseases affecting the smooth muscles of the esophagus and its innervation, disrupting peristalsis or the function of the lower esophageal sphincter, or both.

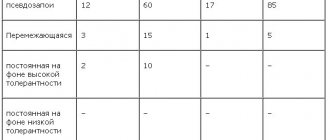

Table 1. Most common causes of esophageal dysphagia

| Foreign bodies in the lumen of the esophagus (usually cause acute dysphagia) |

Damage to the mucosa

|

Mediastinal diseases

|

Diseases affecting smooth muscle and its innervation

|

5. Clinical diagnosis

5.1 Introduction

An accurate examination that takes into account all key diagnostic elements is very important and often allows the diagnosis to be made with complete certainty. It is very important to accurately determine the location where the patient experiences difficulty swallowing (oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia).

5.2 Diagnosis and treatment measures for oropharyngeal dysphagia.

The timed water swallow test is an inexpensive and potentially useful screening test that complements history and clinical examination.

The test involves the patient drinking 150 ml of water from a glass as quickly as possible, while the examiner records the time and number of sips. From these data, the rate of swallowing and the average swallow volume can be calculated. This test is reported to have a predictive accuracy for identifying dysphagia of >95%. This test can be supplemented with a “food test” using a small piece of pudding placed on the back of the tongue (6).

While the water swallow test can be used to establish the diagnosis of dysphagia, it is not useful for detecting aspiration in the 20–40% of cases that follow fluoroscopy because the cough reflex is absent. More specific and reliable tests for assessing dysphagia should be those that depend on the characteristics of the patient and the severity of his/her complaints. In this regard, it should be noted that fluoroscopic examination of the swallowing process (also known as “modified contrast radiological examination”) is the gold standard in the diagnosis of oroesophageal dysphagia, and nasoendoscopy is the gold standard for assessing the morphological causes of dysphagia (7,8,9). Fluoroscopic examination can be used for television broadcast over the Internet, facilitating interpretation of the examination in remote locations (10). Fluoroscopy may also help prevent the risk of aspiration pneumonia (11).

The algorithm below provides guidance for more complex tests and procedures necessary to perform diagnostic studies necessary to select specific therapy.

Algorithm 1. Evaluation and treatment of oroesophageal dysphagia

5.3 Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal dysphagia

5.3.1. Medical history should be considered first

The main task in the case of esophageal dysphagia is to exclude a malignant process. The history of the disease may provide clues in this regard; malignancy may be suspected if:

- Disease duration is short (< 4 months)

- The disease progresses

- Dysphagia is more pronounced when eating solid rather than liquid foods

- There is weight loss

Achalasia is more likely if:

- Dysphagia occurs after eating both solid and liquid foods

- The problem has existed for many years

- No weight loss

There is some controversy regarding the choice of diagnostic tests, which concerns the choice of the primary method of examination - either endoscopy or barium swallow.

5.3.2. Barium - contrast esophagogram (barium swallow)

A barium esophagogram—performed in the right lateral decubitus position—can reveal irregularities in the lumen of the esophagus and identify areas of obstruction, tissue lesions, and rings. Barium studies of the oropharynx and esophagus during swallowing are the most appropriate initial tests; it may be useful in detecting achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm, although this pathology can be more accurately diagnosed using manometry. Such a study can be carried out using a barium tablet, which can detect even minor strictures. Esophageal barium swallow testing may also be useful in patients with dysphagia when endoscopy is negative.

5.3.3. Endoscopic examination

Endoscopy is performed using a fiberoptic endoscope passed through the mouth into the stomach with detailed visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The process of inserting an endoscope into the gastric cavity is very important to exclude pseudoachalasia associated with a tumor of the esophagogastric junction.

Below is the decision-making algorithm.

5.3.3. Other diagnostic tests

- Esophageal manometry

This diagnostic method is less accessible than contrast/barium X-ray and endoscopy, but may be useful in selected cases. The method is based on measuring pressure in the lumen of the esophagus using solid or hydraulic measuring equipment. Manometry is indicated for use in cases where it is assumed that the cause of esophageal dysphagia cannot be identified either by X-ray examination or by endoscopy, and adequate antireflux therapy has been carried out (with cure of esophagitis, which is detected by endoscopy).

The three main causes of dysphagia that can be identified using manometry are: achalasia, scleroderma (ineffective esophageal peristalsis) and esophageal spasm.

- Radionuclide scintigraphy of the esophagus.

The patient swallows a liquid containing a radioactive tracer (for example, water mixed with Technetium 99 and colloidal sulfur) and then the radioactivity of the esophagus is measured. In patients with impaired contractility of the esophagus, a slow release of the radioactive tracer from the esophagus is typical. This technique was originally used for research purposes, but is now beginning to be used for clinical purposes in some specialized institutes.

6. Choice of treatment

6.1. Oropharyngeal dysphagia

There are several treatments for oropharyngeal dysphagia because the neurological and neuromuscular disorders that cause dysphagia can rarely be treated with medications or surgery. Notable exceptions are treatments for Parkinson's disease and myasthenia gravis. Techniques for treating complications are very important. In this regard, identifying the risk of aspiration is a key element in choosing a treatment modality.

Nutrition and diet

Changing your diet to soft foods and choosing a specific posture when eating them is helpful. Oral feeding is superior to other methods of obtaining food if possible. Changing the consistency of food to a thick liquid and eating soft foods will make a significant difference (12). Attention must be paid to food control and nutritional needs (risk of dehydration). Adding citric acid to food improves swallowing reflexes, possibly through improved taste and acid stimulation (13). Adjunctive administration of an angiotensin converting factor inhibitor to relieve the cough reflex may also be beneficial (14).

When there is a high risk of aspiration or when oral intake does not provide adequate nutrition, alternative methods of nutritional support should be considered. A soft feeding tube with sufficient internal diameter can be passed down under x-ray guidance. Feeding gastrostomy after stroke reduces mortality and improves nutritional status compared with the orogastric feeding method. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy allows a gastrostomy tube to be inserted into the stomach through a percutaneous entrance into the abdominal cavity under the supervision of an endoscopist and, if possible, is preferable to surgical gastrostomy. The likelihood that the feeding tube will ever be removed is very low in elderly patients, those suffering from bilateral stroke, or in whom aspiration has occurred on initial fluoroscopic examination (15).

Surgical treatments are aimed at relieving spastic cases of dysphagia, and cricopharyngeal myotomy can be successful in up to 60% of cases, but its effectiveness remains controversial (16). On the other hand, removal of a mechanical obstruction, such as a large, compressing Zenker's diverticulum, often helps.

Swallowing retraining

Various swallowing therapy techniques are being developed to alleviate impaired swallowing. It includes: strengthening exercises, biofeedback stimulation, thermal and gustatory stimulation.

6.2. Esophageal dysphagia

Table 2 below provides a list of treatment options for esophageal dysphagia that may be considered.

Table 2.

| State | Conservative treatment | Invasive |

| Diffuse spasm of the esophagus | Nitrates, calcium channel blockers | Serial dilatation or longitudinal myotomy |

| Achalasia | Soft foods, anticholinergics, calcium channel blockers | Dilatation, botulinum toxin injection, Heller myotomy |

| Scleroderma | Antireflux drugs, systemic drug therapy for scleroderma | Absent |

| GERD | Antireflux drugs (proton pump inhibitors) | Fundoplication |

| Infectious esophagitis | Antibiotics (nystatin, acyclovir) | Absent |

| Pharyngoesophageal (Zenker's) diverticulum | Absent | Endoscopic or external (traditional) repair after crico-pharyngeal myotomy |

| Shatsky's ring | Soft food | Dilatation |

6.2.1. Peptic stricture

Peptic stricture usually results from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and can be caused by certain medications.

In differential diagnosis it is necessary to exclude:

- caustic stricture after ingestion of a corrosive substance

- drug-induced stricture

- postoperative stricture

- fungal stricture

After confirmatory endoscopy, dilatation is the method of choice; its technique is given below.

Esophageal strictures should be dilated in a vigorous manner using Savary bougies or balloons. The choice of the type of dilator should be based on the experience of its use in a given institute and the experience of the operator, as well as the convenience of its use, since the literature does not make it possible to identify the advantage of one type of dilator over another.

If dilatation is performed using bougies, the diameter of the first bougie should be approximately equal to the identified diameter of the stricture. The diameter of the inserted bougies is increased until the insertion resistance reaches the value at the first insertion, after which two more subsequent bougies can be additionally inserted during one procedure. If a balloon dilator is used, the initial dilation should be limited to a diameter of no more than 45F. The degree of initial dilatation of the stricture does not seem to influence either recurrence or the need for repeat dilatation, so the concept of aggressive dilatation to prevent recurrence is weakly supported. The degree of dilatation in each patient should be based on the patient's reactions to the treatment and the difficulties that arise during dilatation. Experience has shown that most patients achieve good dysphagia relief at a diameter between 40F and 45F. Strictures generally should not dilate beyond 60F in diameter.

Vigorous antireflux therapy using proton pump inhibitors or fundoplication improves dysphagia and reduces the need for subsequent esophageal dilatation in patients with peptic esophageal strictures. In patients with persistent dysphagia or in cases of disease relapse after dilatation and antireflux therapy for the first time, cure of reflux esophagitis must be endoscopically confirmed before repeated dilatation. If a positive treatment effect is obtained, the need for subsequent dilatation is decided empirically. Those patients who experienced only short-term relief after dilatation can be taught the self-bouging technique. In the presence of refractory strictures, an attempt to inject hormones into the strictures may be considered. In rare cases, in the presence of true refractory strictures, resection of the esophagus and its reconstruction are required. In exceptional cases, in the presence of benign strictures, endoluminal replacement may be recommended (17). The risk of perforation is about 0.5%. In cases of obvious perforation, surgical treatment is usually indicated.

Below is an algorithm for choosing a treatment method.

Drug therapy with nitrates or calcium channel blockers is often ineffective or poorly tolerated. Botulinum toxin injections may be used as initial therapy in patients at low risk for surgery when it is suspected that drug therapy or bougienage will be poorly tolerated. Botulinum toxin injections are a safe procedure that can induce a state of remission for at least 6 months in approximately 2/3 of patients with achalasia. However, most patients will require repeated injections to maintain remission and only 2/3 of patients with remission at 6 months will remain in remission for up to 1 year despite repeated toxin injections. In cases where this type of treatment fails, the physician and patient must decide whether the benefits of pneumatic dilatation or myotomy outweigh the risks in elderly or debilitated patients. A feeding gastrostomy tube is a safe alternative to pneumatic dilatation and myotomy, but many neurologically intact patients find life with a gastrostomy tube unacceptable.

7. References

- Dysphagia - ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract. William Owen BMJ 2001;323:850-853 Pubmed-Medline

- A Technical Review on Treatment of Patients with Dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus Gastroenterology. July 1999; 117(1): 233-54. Pubmed-Medline

- Oesophageal motility disorders Joel E Richter The Lancet; 8 September 2001; 358/9284;823-828. Pubmed-Medline

- Current concepts expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract Baron Todd H New England Journal of Medicine; 2001 May 31; 344 (22);1681-1687 Pubmed-Medline

- Plummer-Vinson syndrome Atmatzidis-K, Papaziogas-B, Pavlidis-T, Mirelis-Ch, Papaziogas-T. Diseases of the Esophagus 2003, 16/2 (154-157) Pubmed-Medline

- Dysphagia in patients with nasopharyngeal cancer after radiation therapy: A videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Chang-YC, Chen-SY, Lui-LT, Wang-TG, Wang-TC, Hsiao-TY, Li-YW, Lien-IN. DYSPHAGIA, 2003, Vol/Iss/Pg. 18/2 (135-143). Pubmed-Medline

- Morphological findings in dynamic swallowing studies of symptomatic patients. Scharitzer-M, Pokieser-P, Schober-E, Schima-W, Eisenhuber-E, Stadler-A, Memarsadeghi-M, Partik-B, Lechner-G, Ekberg-OM Scharitzer European Radiology EUR-RADIOL, 01 MAY 2002, 12/5 1139-1144). Pubmed-Medline

- Visualization of swallowing using real-time true FISP MR fluoroscopy. Barkhausen-J, Goyen-M, von-Winterfeld-F, Lauenstein-T, Debatin-JF European Radiology 01 JAN 2002, 12/1 (129-133). Pubmed-Medline

- Early assessments of dysphagia and aspiration risk in acute stroke patients. Ramsey-DJC, Smithard-DG, Kalra-L. Stroke 01 MAY 2003, 34/5 (1252-1257). Pubmed-Medline

- Real-time remote telefluoroscopic assessment of patients with dysphagia. Perlman-AL, Witthawaskul-W. Dysphagia 2002, 17/2 (162-167). Pubmed-Medline

- Videofluoroscopic studies of swallowing dysfunction and the relative risk of pneumonia. Pikus-L, Levine-MS, Yang-YX, Rubesin-SE, Katzka-DA, Laufer-I, Gefter-W American Journal of Roentgenology 01 JUN 2003, 180/6 (1613-1616). Pubmed-Medline

- Tolerance of early diet textures as indicators of recovery from dysphagia after stroke. Wilkinson-TJ, Thomas-K, MacGregor-S, Tillard-G, Wyles-C, Sainsbury-R. Dysphagia, 2002, 17/3 (227-232). Pubmed-Medline

- Effect of citric acid and citric acid-sucrose mixtures on swallowing in neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia. Pelletier-CA, Lawless-HT. Dysphagia 2003, 18/4 (231-241). Pubmed-Medline

- Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Marik-PE, Kaplan-D. Chest 01 JUL 2003, 124/1 (328-336). Pubmed-Medline

- Predictors of Feeding Gastrostomy Tube Removal in Stroke Patients With Dysphagia. Ickenstein-GW, Kelly-PJ, Furie-KL, Ambrosi-D, Rallis-N, Goldstein-R, Horick-N, Stein-J. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2003, 12/4 (169-174).

- Quality of life following surgical treatment of oculopharyngeal syndrome. Gervais-M, Dorion-D. Journal of Otolaryngology 2003, 32/1(1-5). Pubmed-Medline

- Relapsing cardial stenosis after laparoscopic Nissen treated by esophageal stenting. Pouderoux-P, Verdier-E, Courtial-P, Bapin-C, Deixonne-B, Balmes-JL. Dysphagia 2003, 18/3 (218-222) Pubmed-Medline

8. Useful websites

- Medical Position Statement on the Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia; Gastroenterology 1999; 116; 452-478 Link

- Diagnosis and Management of Achalasia. Practice Guideline. The American Journal of Gastroenterology; 1999; 94/12;3406-3412. Link

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria for imaging recommendations for patients with dysphagia - Radiology 2000 June; 215 (suppl) 225-230. Link

- Management of patients with stroke; III Identification and management of Dysphagia; SIGN Guideline No. 20; pilot edition november 1997; Link

- Diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders (dysphagia) in acute care stroke patients. (ACHPR-99-E023. Rockville: AHCPR, 1999). Link

- M. Louay Omran, Dysphagia. Link

- Clinical Use of esophageal manometry; AGA Medical Position statement; reviewed 2001. Link

- Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration. American Society of Anesthesiologists Anesthesiology 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905. Link

9. Reader comments and feedback

Invitation to Comments

The committee that wrote this guide welcomes comments and suggestions from readers. If you think that some aspects of the problem are not sufficiently covered, if you have good experience in solving these problems, then share it with the authors of the manual. Together we can make it even better!

Degrees

Depending on the symptoms present, dysphagia is divided into 4 degrees of severity:

- The first is the inability to swallow certain types of solid food.

- Second, the patient eats only soft food; swallowing any hard food is impossible.

- Third, at this stage it is possible to swallow only liquid food.

- The fourth is a severe form with the inability to swallow any food.

Any degree of dysphagia is accompanied by characteristic symptoms and pain in the pharynx or chest. The last severe stage is characteristic, as a rule, of risk grade 4 cancer.

Any type of dysphagia is life-threatening for the patient, so a doctor should be consulted when the first symptoms occur. If your health suddenly worsens at night, you should not postpone your visit to the hospital until the morning. In this case, you can contact the 24-hour Yusupov Hospital, where the necessary medical care will be provided.

Symptoms of dysphagia

The disease is always accompanied by characteristic symptoms that are difficult to miss. Depending on the location of the pathological process, the manifestations of the disease may vary:

Oropharyngeal dysphagia

This species is characterized by severe cough syndrome, increased salivation and reflux of food into the nasopharynx cavity. When the disease occurs, the patient cannot swallow completely. It takes effort to move food through the esophagus.

The process of eating food is quite painful and causes pain in the oropharynx, as well as in the chest area. Due to the pathological process, appetite is lost, which often leads to exhaustion. Many patients complain of hoarseness and hoarseness.

The symptoms are almost identical to cricopharyngeal incoordination. The only difference is that the second type of disease is more dangerous due to the risk of pathological processes occurring in the lungs.

Esophageal dysphagia

Unlike the oropharyngeal type, the symptoms of food dysphagia are different, since the process of swallowing food is not impaired. The peculiarity of this pathology is that the passage of liquid and solid food through the esophagus is difficult. Among the symptoms, patients experience severe heartburn, pain behind the sternum and in the upper abdomen.

Also, the esophageal type is characterized by frequent belching, after which an unpleasant sour taste occurs in the mouth. In this case, the contents of the stomach are often thrown into the oral cavity and pharynx. Increased regurgitation (movement of gastric contents) occurs when the body bends forward or during sleep. Especially if the last meal was taken less than 1-2 hours before bedtime.

Pain during eating is reduced if the patient drinks water with his food. At the same time, the process of passing the food bolus is facilitated. Both pathologies have identical manifestations - disruption of the gastrointestinal tract, loss of appetite and weight, as well as depression due to the inability to eat properly.

Methods for assessing dysphagia and preventing aspiration in palliative patients

The “About Palliative” portal held the third webinar of the series “Doctors to doctors: the basics of palliative care” on the topic “Methods for assessing dysphagia and preventing aspiration in palliative patients. Technique for placing a nasogastric tube." Based on his materials, we prepared an article in which we tried to describe all the problems with swallowing disorders in seriously ill patients.

Just yesterday you happily ate rich borscht for lunch and dined on a crispy meat casserole, but today you literally can’t get a bite into your throat. The body seems to have “forgotten” how to swallow, and this sensation causes first confusion, and then fear and, possibly, pain. Has it ever occurred to you that your natural ability to swallow food or liquid might go somewhere? You chew your food diligently, endlessly turning it around in your mouth in the hope that everything will work out on its own. But time passes, your loved ones begin to get annoyed by the prolonged meal, it seems to them that you are deliberately testing their patience, and you realize with horror that the process of eating food from a habitual pleasure is rapidly turning into inevitable torture.

This is dysphagia.

Swallowing disorder. A syndrome known to almost every doctor since residency. Fortunately, most of them have never experienced it themselves, and therefore do not always imagine how the patient feels. But dysphagia is a colossal psychological trauma for a person, because “basic,” natural functions are disrupted, which means that he expects from a doctor not only relief from discomfort, but also human support and understanding. Key principles and technologies of nutritional support in palliative medicine Doctor Ilya Leiderman on who needs nutritional support, what the indications may be and when to use parenteral nutrition Ilya Leiderman

Symptomatic treatment

Dysphagia is quite common in palliative patients. Against the background of the general serious condition of such patients, and often a depressed state of mind, people experience this symptom especially difficult. This means that the doctor requires not only professional help, but also a sensitive, friendly attitude, attention to detail, which can make the life of patients a little more comfortable and easier.

Varvara Nikolaevna Brusnitsyna, head of the long-term respiratory support department and the department of palliative care No. 3, anesthesiologist-resuscitator, rehabilitation specialist, Moscow Multidisciplinary Center for Palliative Care, Department of Health.

Dysphagia grades

First of all, it is necessary to determine what degree of dysphagia the patient has. There are four degrees. If with the first and second the patient can be helped by a properly selected diet, then in the case of the third, and especially the fourth degree, there is already a significant risk to life, which means the nutrition process must be organized in a completely different way.

Dysphagia risk assessment framework

Grade 1 - the patient has difficulty swallowing only certain types of solid food. Usually, he notices this himself and switches to food of a softer consistency. For example, instead of fried potatoes or hard vegetables, he chooses mashed potatoes.

At grade 2, a gradation appears between soft and hard foods. The patient cannot swallow solids at all, even after chewing them thoroughly. When I try to do this, I choke.

At stage 3 , even liquid and soft food does not “go in”. From the usual puree, the patient coughs, it becomes difficult for him to breathe, and sometimes his face may even turn blue.

Stage 4 - the patient cannot even swallow his own saliva.

The presence of dysphagia and its degree can be determined in different ways. First, if the patient's condition allows, simply ask him about it. An ordinary, human conversation about what a person has eaten, whether there have been any changes in his taste preferences recently, will not only help to quickly identify possible problems, but will also improve the psychological state of the patient - we all enjoy it when people are interested in us.

Secondly, be careful. With the constant flow of urgent cases, it can be difficult for a doctor to notice any minor changes, so here the main burden falls on junior medical staff and nurses. They are the ones who notice the smallest nuances in the condition and behavior of patients. For example, they may note that a couple of days ago it took half an hour to feed one patient, but now it takes almost two, because he began to hold food in his mouth for too long. Or notice that another patient began to cough too often and sometimes turn blue.

Of course, anyone can cough when a piece of food gets into the trachea - “in the wrong throat” as people say, but when one spoon coughs, then a second, a third... These are already symptoms of a swallowing disorder.

As well as gurgling sounds in the throat, which are sometimes mistaken for almost pulmonary edema, actually indicate a severe degree of dysphagia.

Thirdly, there is a method for determining dysphagia - screening. It can be carried out not only in the hospital, but also at the patient’s home. Screening instructions were developed by the Federal Center for Cerebrovascular Pathology and Stroke. It is automatically included in the medical records of all patients admitted to the neurological hospital. Screening must be carried out by a doctor or nurse in emergency departments in city hospitals and in intensive care units. It is an integral part of the examination in a palliative care center.

When can screening be done?

Screening is carried out in two stages. The first stage consists of preliminary questions, by answering which the medical professional understands whether it is possible to proceed directly to the test or whether the patient’s condition does not allow this.

Swallowing screening test schedule. Step 1.

These questions are designed for urban hospitals. Screening is carried out if all answers to them are positive (except for the last one). However, this is not the case for palliative patients.

For example, the question: is the patient awake or likely to be awakened? Does he respond to requests? Palliative patients with neuromuscular pathology cannot always respond vocally, but being in clear consciousness, they can respond alternatively.

The second question also does not apply to palliative patients. Many of them are too weak to sit up on their own.

Palliative care for patients with ALS Breathing and swallowing disorders, communication difficulties and other symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Vadim Parshikov

Symptomatic treatment

Next: Can the patient cough if asked to do so? But patients with neuromuscular diseases very often have a reduced cough impulse. They try to cough, but cannot and begin to get nervous. This does not mean in this case that screening cannot be done. The same goes for the ability to control saliva: patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis may drool a lot, but that doesn't mean they can't swallow.

However, if the patient cannot swallow his saliva at all, which corresponds to stage 4 dysphagia, screening cannot be performed.

The question of breathing is also not always legitimate for palliative patients. Sometimes they may be on a ventilator without losing their ability to swallow.

Important Essentially, the only criterion for screening for dysphagia in palliative patients is clear consciousness and the ability to swallow their saliva.

How to carry out screening?

All you need for screening (also called the “three-sip test”) is a spoon, water and a regular glass.

First, the patient is asked to take three sips from a spoon in succession, and then drink half a glass of water. According to research by neurophysiologists, if a person copes with just such a load (no choking, choking, bubbling breathing), this means that he has no problems with swallowing.

If difficulty occurs at any stage, this means that the patient has grade 1 or 2 dysphagia. If the patient cannot take a single sip (although he swallows saliva) - this is already stage 3, which means that the chart must be marked as NSR (nothing by mouth) and strictly ensure that the patient does not receive nutrition in the usual way.

Important Cough, choking, shortness of breath, hoarse voice are predictors of dysphagia in the patient.

Swallowing screening test schedule. Step 2.

How to help?

In case of dysphagia of 1st and 2nd degrees, while maintaining clear consciousness, and also when the patient’s digestive tube function is absolutely stable, that is, everything is normal with absorption, with digestion, there are no obstructions, obstructions and other contraindications, you can use mixtures for siping of varying degrees of thickening. Siping is a way to take a mixture in small sips, and since it is more convenient to do this through a straw, siping mixtures are usually available in bottles with a straw. Or you can use OVD (the main diet option) also with a thickener.

A thickener is a colorless and odorless powder that, when added to any liquid food or water, turns it into a thick jelly. There are thickeners with different flavors - vanilla, fruit. Unfortunately, not all patients like them, so the amount of thickener must be adjusted individually in each case.

For grade 3 and 4 dysphagia, with preserved gastrointestinal function and the absence of contraindications (this consciousness does not have to be clear), tube feeding is recommended - through a nasogastric tube, nasointestinal tube, gastrostomy or jejunostomy.

Important: Attempting to feed a patient with grade 3 or 4 dysphagia orally may result in aspiration!

Aspiration is the penetration of liquid or solid substances into the respiratory tract (food debris, saliva, pieces of tissue, blood, artificial teeth and other objects that should not be there).

Aspiration is life-threatening and extremely painful. The mucous membrane of the trachea and bronchi is very richly innervated. Food from the stomach mixed with hydrochloric acid literally burns it, causing severe pain to the patient.

How to assess the risk of aspiration?

Theoretically, anyone is at risk of aspiration. In a hurry to eat something tasty, especially when we are hungry, we risk choking, and this can lead to aspiration. We are also sure to choke if we eat lying down without raising our heads. But in these cases, if we are talking about a healthy person, the risk of aspiration is assessed as low.

At the palliative care center, the risk of aspiration was divided into three groups: low, medium and high.

The risk of aspiration is low if:

- the patient is clearly conscious and adequate,

- he successfully passed the three-sip test, meaning he does not have dysphagia,

- everything is fine with the digestive tube and the passage of food masses.

Signs of low risk of aspiration. Prevention measures.

An average risk of aspiration is present if the patient has a tube, gastrostomy or tracheostomy tube installed, but there is no disturbance in the passage of food masses, and the person is clearly conscious and adequate.

The fact is that the installed probe keeps the cardia always open. If the patient lies incorrectly when feeding, food may leak past the tube and into the trachea. Especially if the patient has grade 1 dysphagia. With a gastrostomy, the cardia also cannot close after each meal, because the food bolus simply does not pass through it, but goes directly into the stomach.

Signs of moderate risk of aspiration. Prevention measures.

A high risk of aspiration is present when the patient has impaired consciousness, the three-sip test is negative or for some reason the test cannot be performed, and there is also a nasogastric tube or tracheostomy tube.

Signs of a high risk of aspiration. Prevention measures.

Important The risk of aspiration varies among patients. Therefore, screening for dysphagia should be performed at regular intervals depending on the patient's condition.

A mandatory rule for feeding all patients: raise the head end of the bed (if possible, sit the patient down) and do not lower it for 40 minutes after finishing feeding.

Caring for a gastrostomy tube Basic rules and algorithms for caring for a gastrostomy tube, the skin around the stoma and the oral cavity Vera Foundation

Care

Common Misconceptions

The three-sip test is enough to do once. Not at all. The dynamics of patients vary. Seeing improvements in consciousness, you must definitely do screening as many times as required.

The patient does not need to be fed orally if he or she has a tube. It is necessary if he has a swallowing reflex. If the patient quickly gets tired of swallowing, and you understand that he is not able to finish his daily allowance, he should be supplemented through a tube. But you need to “train” swallowing even with a probe at the slightest opportunity.

The presence of a gastrostomy eliminates oral nutrition. This is not always the case. Gastrostomies are placed for various indications. Sometimes it’s preventive—that is, the patient doesn’t have dysphagia yet, but given the diagnosis, doctors understand that it will appear. If the patient has preserved swallowing or dysphagia with a normal BPV, he can be fed orally. This is especially important from a psychological point of view. After all, food is one of the greatest pleasures, and a seriously ill person doesn’t have many of them anyway.

Read about the placement of a nasogastric tube, the rules of feeding through a tube and the prevention of complications in the second part of the article, coming soon!

The material was prepared using a grant from the President of the Russian Federation for the development of civil society provided by the Presidential Grants Foundation.

Diagnosis of dysphagia

To make an accurate diagnosis, it is necessary to undergo a series of clinical examinations. Pathology cannot be detected by visual inspection and palpation. To determine the type of disease and severity, the doctor collects complete information - when the pathology occurred, what symptoms are present, whether there are any chronic diseases, etc. After this, the specialist carefully examines the patient and then prescribes:

- General and biochemical blood test to detect inflammatory processes. FGDS (fibrogastroduodenoscopy) for a detailed study of the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal tract;

- Fecal analysis (coprogram), which allows to identify the remains of undigested food fibers and determine the level of functioning of the gastrointestinal tract;

- Laryngoscopy - instrumental examination of the larynx and vocal cords;

- The examination is carried out for all patients who have complaints of disorders of the ENT organs;

- Ultrasound (ultrasound examination) - examination of the pancreas, biliary tract and other abdominal organs. This is necessary in order to identify or exclude structural changes leading to the formation of dysphagia;

- Irrigoscopy is an X-ray examination of the esophagus with the introduction of a special contrast liquid. The diagnostic method helps determine the degree of narrowing of the esophagus;

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is a study of the brain for the presence of pathologies that may influence the development of dysphagia. It is prescribed if no mechanical obstacles to the passage of food were identified during previous activities.

Diagnostic measures are very important, since the correctness of further treatment and its effectiveness depend on the accuracy of the diagnosis. To eliminate the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis and incorrect prescription of therapeutic measures, you can contact highly qualified specialists at the 24-hour Yusupov Hospital. Many years of experience allows us to accurately determine the type of pathology and eliminate it in the shortest possible time.

Treatment of dysphagia

Therapy is prescribed after diagnostic measures have been carried out. Depending on the type of pathology, treatment can be medication or surgical interventions.

Medications

- If the cause of the pathology is increased acidity of the gastric juice, medications are prescribed that reduce its levels - Almagel, Phosphalugel, Zantac.

- In case of pathology caused by bacterial infections, antibiotics are prescribed, the group of which is determined by the doctor. This could be Ceftriaxone, Levobax, Levoximed.

In addition, anti-inflammatory drugs and medications that eliminate the present symptoms - antiemetics, painkillers and other pharmacological groups - can be prescribed.

Operation

Surgery is used if there is no therapeutic effect from drug therapy. Most often, manipulations are performed for dysphagia caused by cancerous tumors, chemical burns of the esophagus, or severe inflammatory lesions. After surgery, the patient requires bed rest in a hospital setting.

Diet therapy

Diet therapy is also important for dysphagia. It involves eating frequent meals in small portions. During the rehabilitation period it is necessary to exclude:

- Alcohol products;

- Fatty, fried, spicy foods;

- Fast food products;

- Smoked meats, saltiness, spices and herbs.

While eating, food must be chewed thoroughly, avoiding swallowing large pieces.

The disease is quite dangerous and requires a competent approach from a certified specialist. In this case, it is important to choose the right doctor, because the final result and prognosis depend on this. With incorrect manipulations, there is a risk of developing aggravating consequences and the pathology becoming severe.

By turning to the Yusupov Hospital, the patient provides himself with safe and effective treatment without complications, which is guaranteed to lead to quick relief from severe pathology. In addition, in the clinic you can undergo a rehabilitation course under the close supervision of a doctor and prevent the recurrence of dysphagia.

Medicines are taken only in consultation with a doctor. Self-medication in all cases aggravates the situation and leads to dangerous complications.

The term "dysphagia" refers to either the difficulty a person may experience during the primary phases of swallowing (usually described as "oropharyngeal dysphagia") or the feeling that food or liquid is somehow blocked during passage from the mouth to the stomach (usually described as "esophageal dysphagia"). Thus, dysphagia is the feeling of an obstacle to the normal passage of swallowed material. Food entrapment [1] is a specific symptom that may occur periodically in these patients.

Oropharyngeal swallowing is a process controlled by the swallowing center in the medulla oblongata, and in the middle and distal parts of the esophagus by an almost autonomous peristaltic reflex, coordinated by the enteric nervous system. Table 1

shows the physiological mechanisms involved in the various phases of this process.

Table 1

Physiological mechanisms involved in the stages of swallowing, by phase

The key question is whether the dysphagia is oropharyngeal or esophageal. This distinction can be made with confidence based on a careful history, which provides an accurate assessment of the type of dysphagia (oropharyngeal or esophageal) in approximately 80–85% of cases [2]. More precise localization is unreliable. The main points to consider in the medical history (specifics discussed below) are:

- Place of origin

- Types of food and/or liquid

- Progressive or periodic

- Duration of symptoms

Although these conditions often occur together, it is also important to rule out odynophagia (painful swallowing). Finally, the differential diagnosis based on symptoms should exclude globus pharyngeus (lump in the throat), intrathoracic pressure, dyspnea, and phagophobia (fear of swallowing).

1.1 Causes of dysphagia

When the clinician is trying to determine the etiology of dysphagia, it is useful to resort to the same classification used to evaluate symptoms - that is, to distinguish between causes primarily affecting the pharynx and proximal esophagus (oropharyngeal or "high" dysphagia) on the one hand, and causes most often related to the body of the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction (esophageal or “lower” dysphagia) on the other. However, it is true that many disorders can overlap and cause both oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia. A thorough history, including medication use, is important as medications may be involved in the pathogenesis of dysphagia.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia

In young patients, oropharyngeal dysphagia most often occurs due to diseases of the muscles, connective tissue, or rings. In older patients, it is usually caused by central nervous system disorders, including stroke, Parkinson's disease and dementia. Normal aging can cause mild (rarely symptomatic [3]) esophageal motility disorders. Dysphagia in older patients should not be automatically attributed to normal aging.

In general, it is helpful to try to distinguish between mechanical problems and neuromuscular mobility disorders, as shown below.

Mechanical and obstructive causes:

- Infections (eg, retropharyngeal abscesses)

- Thyroid enlargement

- Lymphadenopathy

- Zenker's diverticulum

- Decreased muscle response (myositis, fibrosis, cricopharyngeal adhesion)

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Malignant neoplasms of the head and neck and the consequences (eg, dense fibrotic strictures) of surgery and/or radiotherapy on these tumors

- Cervical osteophytes

- Oropharyngeal malignancies and neoplasms (rare)

Neuromuscular disorders:

- Central nervous system diseases such as stroke, Parkinson's disease, cerebral or bulbar palsy (eg, multiple sclerosis, motor nerve disease), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Contractility disorders, such as myasthenia gravis, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy and others.

Within 3 days of stroke, 42–67% of patients develop oropharyngeal dysphagia, making stroke the leading cause. Among these patients, 50% experience aspiration and one third develop pneumonia requiring treatment [4]. The severity of dysphagia tends to be related to the severity of stroke. Screening for dysphagia among stroke patients is very important to prevent negative outcome due to aspiration and inadequate hydration/nutrition [5].

Up to 50% of patients with Parkinson's disease demonstrate symptoms similar to oropharyngeal dysphagia, and almost 95% have pathology detected on video esophagography [6,7]. Clinically significant dysphagia may appear early in Parkinson's disease but usually develops later in life.

Esophageal dysphagia

Table 2

Most common causes of esophageal dysphagia

1.2 VGO cascades - global practical recommendations

Cascades - resource-based approach

A gold standard approach is only feasible if a full range of diagnostic tests and drug treatment options are available.

Such resources for diagnosing and treating dysphagia may not be sufficiently available in every country. The World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) practice guidelines provide a resource-based approach in the form of diagnostic and treatment cascades. The VGO cascade is a hierarchical set of diagnostic, therapeutic, and risk and disease management options, separated by the availability of resources.

Other publicly available best practices

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria®dysphagia. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology, 2013. Available at: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69471/Narrative/

- Australian and New Zealand Society of Geriatric Medicine. Position statement—dysphagia and aspiration in older people. Australas J Ageing 2011;30:98–103. Available at: https://www.anzsgm.org/posstate.asp.

- Scottish Intercollege Practice Advice Network. Management of patients with stroke: identification and management of dysphagia. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2010. Available at: https://sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html

- Speech Pathology Association of Australia. Clinical guideline: dysphagia. Melbourne: Speech Pathology Australia, 2012. Available at: https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/library/Clinical_Guidelines/

1.3 Disease burden and epidemiology

Dysphagia is a common problem. One in 17 people will develop some form of dysphagia during their lifetime. A 2011 UK study shows a prevalence of dysphagia of 11% in the general population [9]. The condition develops in 40–70% of patients with stroke, 60–80% of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, nearly 13% of adults aged 65 and older, and >51% of elderly patients in nursing homes [10,11]. It also affects 60–75% of patients receiving radiotherapy for head and neck cancer.

The disease burden of dysphagia is clearly described in a US congressional resolution in 2008 [12], which notes that:

- Dysphagia affects nearly 15 million Americans; All Americans over 60 years of age experience dysphagia at one time or another.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 million people in the United States are diagnosed with dysphagia each year.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality shows that 60,000 Americans die annually from complications related to dysphagia.

- Complications caused by dysphagia increase the cost of medical care due to repeated hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, prolonged hospital stays, the need for a long rehabilitation course, and the need for expensive respiratory and nutritional support.

- Including hospital costs, the total cost of dysphagia to the health care system is well over $1 billion annually.

- Dysphagia is a condition that is underreported and not well understood by the general public.

Global epidemiological data are difficult to generalize because the incidence of most diseases causing dysphagia tends to vary between regions and continents. Therefore, at the global level, it is only possible to talk about approximate data. Frequency levels also vary depending on the age of the patient, and it must be remembered that the range of disorders associated with childhood dysphagia differs from that in older age groups. In younger patients, dysphagia is often seen with head and neck injuries and with cancer of the neck and mouth. Dysphagia generally occurs in all age groups, but its frequency increases with age.

The incidence of tumors varies among countries. In the US and Europe, for example, the most common type of esophageal cancer is adenocarcinoma, while in India and China it is squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, corrosive esophageal strictures (following ingestion of corrosive substances with suicidal intent) and tuberculosis may be important considerations in non-Western countries.

Regional features

- North America/United States: The incidence of reflux strictures in the United States has been declining since the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors [13].

- Eosinophilic esophagitis is increasingly recognized as a major cause of dysphagia in children and adults [13].

- The incidence of esophageal cancer is increasing, although the absolute number of patients diagnosed in the United States remains small.

- With the increasing population of elderly patients in the United States, cervical osteophyte compression, stroke, and other neurological disorders are becoming more important causes of dysphagia than in the past.

- The widespread use of ablative treatments for Barrett's esophagus (radiofrequency ablation, photodynamic therapy, and endoscopic mucosal resection) is likely leading to the emergence of a new group of patients with endotherapy-induced strictures.

- While gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and peptic strictures are decreasing in incidence as causes of esophageal dysphagia, the incidence of adenocarcinoma and eosinophilic esophagitis is increasing [14–16].

- Common causes of esophageal dysphagia are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, achalasia, and surgically treated strictures. The incidence of GERD appears to be increasing, but is still less common in Asia compared to Western countries. Post-stroke dysphagia is quite common in Asia, and improvements in healthcare are gradually leading to its early recognition and treatment.

- Chagas disease is very common in parts of Latin America. Chagastic achalasia and megaesophagus may develop, leading to malnutrition. Some features of Chagas' achalasia differ from idiopathic achalasia. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure tends to be low, apparently due to damage to both excitatory and inhibitory control mechanisms. However, medical and surgical treatment are the same [19].

- In Africa, management of post-stroke dysphagia may be suboptimal due to insufficient available resources or their misallocation. The lack of trained and knowledgeable health care professionals can also result in less than optimal patient management. There are also no specialized stroke wards and instruments, in particular, the equipment necessary to carry out the “gold standard” - a modified barium swallow [20].

Treatment of dysphagia in Moscow

Treatment for dysphagia in Moscow is not difficult to find, but when choosing a clinic, it is important to take into account the experience of specialists in this area, since the prognosis directly depends on this. For many years, the Yusupov Hospital has been specializing in pathologies associated with the esophagus and difficulty swallowing.

The clinic is equipped with the latest equipment, offers comfortable conditions, as well as the most favorable atmosphere for patients. The cost of treatment depends on the complexity of the disease and methods of therapeutic measures. Despite the high level of professionalism of specialists and expensive equipment, the Yusupov Hospital offers its patients the most competitive prices in Moscow.

In addition to treating dysphagia of any degree, the clinic offers the following services:

- Treatment of pathologies of a neuralgic nature - stroke, dementia, epilepsy, parkinsonism, myasthenia gravis and other complex diseases.

- Help for patients with cancer - chemotherapy, immunotherapy, rehabilitation, as well as effective pain-relieving procedures.

- Services of highly specialized specialists - cardiologist, pulmonologist, urologist, gastroenterologist, rheumatologist and others.

- Diagnostic examination using the latest devices from leading global manufacturers.