The best treatment for heart failure is its prevention, which includes treatment of arterial hypertension, prevention of atherosclerosis, a healthy lifestyle, exercise and diet (primarily salt restriction). Treatment of heart failure, begun at the earliest stages, significantly improves the patient's life prognosis.

The main function of the heart is to supply oxygen and nutrients to all organs and tissues of the body, as well as remove their waste products. Depending on whether we are resting or actively working, the body requires different amounts of blood. To adequately meet the body's needs, the frequency and strength of heart contractions, as well as the size of the lumen of blood vessels, can vary significantly.

A diagnosis of heart failure means that the heart has ceased to sufficiently supply tissues and organs with oxygen and nutrients. The disease is usually chronic and the patient may live with it for many years before being diagnosed. Around the world, tens of millions of people suffer from heart failure, and the number of patients with this diagnosis increases every year. The most common cause of heart failure is a narrowing of the arteries that supply oxygen to the heart muscle. Although vascular disease develops at a relatively young age, the manifestation of congestive heart failure is most often observed in older people.

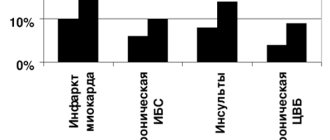

According to statistics, among people over 70 years of age, 10 out of 1,000 patients are diagnosed with heart failure. The disease is more common in women, because In men, there is a high mortality rate directly from vascular diseases (myocardial infarction) before they develop into heart failure.

Other factors that contribute to the development of this disease are hypertension, alcohol and drug addiction, changes in the structure of the heart valves, hormonal disorders (for example, hyperthyroidism - excessive function of the thyroid gland), infectious inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis), etc.

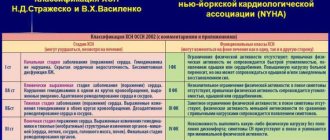

Classifications of heart failure

The world has adopted the following classification, based on the effects that appear at different stages of the disease:

Class 1: no restrictions on physical activity and no impact on the patient’s quality of life. Class 2: mild restrictions on physical activity and complete absence of discomfort during rest. Class 3: noticeable decrease in performance, symptoms disappear with rest. Class 4: Total or partial loss of function, symptoms of heart failure and chest pain occur even during rest.

Classification

There is a classification of CHF according to the stages of development of the disease (N.D. Strazhesko, V.Kh. Vasilenko):

Stage I (initial) - signs of deficiency appear only during physical activity, there are no symptoms at rest.

Stage II is divided into two periods:

- period A – clinically pronounced disorder of the right or left side of the heart, congestion in the pulmonary or systemic circulation, shortness of breath and symptoms occur with little physical effort;

- period B – stagnation in both circles of blood circulation (manifested by shortness of breath, swelling), performance is sharply reduced.

Stage III (final) - changes in the structure of organs and tissues, due to impaired blood supply and trophism, shortness of breath at rest.

The severity of the disease is determined by the functional class (FC), which shows how limited the patient’s physical activity is.

- I FC - no restrictions on physical activity. Normal physical activity does not cause excessive shortness of breath, fatigue, or palpitations;

- FC II - minor limitation in physical activity. Feel comfortable at rest, but normal physical activity causes shortness of breath, fatigue, or palpitations;

- III FC is a clear limitation of physical activity. Feeling comfortable at rest but doing less physical activity than usual causes excessive shortness of breath, fatigue, or palpitations;

- IV FC - inability to perform any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms may be present at rest. With any physical activity, discomfort increases.

The disease should not be allowed to develop; timely diagnosis will help prevent the occurrence of pathology. Our cardiology center of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency invites you to undergo a comprehensive heart examination. Timely identification of the cause of heart failure and its treatment will help maintain your quality of life.

Symptoms of heart failure

Depending on the nature of the disease, acute and chronic heart failure are distinguished.

Manifestations of the disease are:

- slowing down the speed of general blood flow,

- decrease in the amount of blood pumped out by the heart

- increased pressure in the heart chambers,

- accumulation of excess blood volumes, which the heart cannot cope with, in the so-called “depots” - the veins of the legs and abdominal cavity.

Weakness and fatigue are the first symptoms of heart failure.

Due to the inability of the heart to cope with the entire volume of circulating blood, excess fluid from the bloodstream accumulates in various organs and tissues of the body, usually in the feet, calves, thighs, abdomen and liver.

As a result of increased pressure and fluid accumulation in the lungs, a phenomenon such as dyspnea, or breathing difficulties, may occur. Normally, oxygen easily passes from the capillary-rich tissue of the lungs into the general bloodstream, but when fluid accumulates in the lungs, which is observed in heart failure, oxygen does not fully penetrate the capillaries. Low oxygen concentration in the blood stimulates increased breathing. Patients often wake up at night from attacks of suffocation.

For example, American President Roosevelt, who suffered from heart failure for a long time, slept sitting in a chair due to problems with breathing problems.

The release of fluid from the bloodstream into tissues and organs can stimulate not only breathing problems and sleep disorders. Patients suddenly gain weight due to swelling of soft tissues in the feet, legs, thighs, and sometimes in the abdomen. Swelling is clearly felt when pressing with a finger in these places.

In particularly severe cases, fluid may accumulate inside the abdominal cavity. A dangerous condition occurs - ascites. Ascites is usually a complication of advanced heart failure.

When a certain amount of fluid from the bloodstream enters the lungs, a condition characterized by the term “pulmonary edema” occurs. Pulmonary edema often occurs in chronic heart failure and is accompanied by pink, bloody sputum when coughing.

Insufficient blood supply affects all organs and systems of the human body. On the part of the central nervous system, especially in elderly patients, a decrease in mental function may be observed.

Diagnostics

When collecting anamnesis, the doctor pays special attention to the presence of complaints of shortness of breath and fatigue. Collects information about the existence of other diseases. If heart failure is suspected, the patient is referred for instrumental studies and laboratory tests.

The Cardiology Center of the Federal Medical and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency carries out a full range of diagnostic measures:

- ECG in 12 leads;

- ECHO-KG;

- Holter monitoring;

- ECG with dosed physical activity;

- transesophageal ECHO-CG;

- ABPM (24-hour blood pressure monitoring);

- Ultrasound of the abdominal organs;

- general blood analysis;

- biochemical blood test (lipid spectrum, blood glucose, liver and kidney function indicators);

- thyroid hormones;

- coagulogram (a test to determine blood clotting);

- general urine analysis;

- spirometry (respiratory function test);

Left side or right side?

The different symptoms of heart failure depend on which side of the heart is involved. For example, the left atrium (upper chamber of the heart) receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and pumps it into the left ventricle (lower chamber), which in turn pumps blood to the rest of the organs. When the left side of the heart cannot pump blood efficiently, it backs up into the pulmonary vessels and excess fluid flows through the capillaries into the alveoli, causing difficulty breathing. Other symptoms of left-sided heart failure include general weakness and excessive mucus (sometimes mixed with blood).

Right-sided insufficiency occurs when there is difficulty in the outflow of blood from the right atrium and right ventricle, which happens, for example, when the heart valve is not functioning properly. As a result, pressure increases and fluid accumulates in the veins ending in the right chambers of the heart - the veins of the liver and legs. The liver becomes enlarged, painful, and the legs become very swollen. With right-sided insufficiency, a phenomenon such as nocturia or increased nighttime urination is observed.

In congestive heart failure, the kidneys cannot handle large volumes of fluid, and kidney failure develops. Salt, which is normally excreted by the kidneys along with water, is retained in the body, causing even greater swelling. Renal failure is reversible and disappears with adequate treatment of the main cause - heart failure.

Causes of heart failure

There are many reasons for the development of heart failure. Among them, the most important place is occupied by coronary heart disease or insufficient blood supply to the heart muscle. Ischemia, in turn, is caused by blockage of the heart vessels with fat-like substances.

A heart attack can also cause heart failure because some of the heart tissue dies and becomes scarred.

Arterial hypertension is another common cause of insufficiency. The heart requires much more effort to move blood through the spasmodic vessels, which results in an increase in its size, in particular the left ventricle. Later, weakness of the heart muscle or heart failure develops.

Causes that influence the development of heart failure include cardiac arrhythmias (irregular contractions). A number of beats of more than 140 per minute is considered dangerous for the development of the disease, because the processes of filling and ejection of blood by the heart are disrupted.

Changes in the heart valves lead to disturbances in the filling of the heart with blood and can also cause the development of heart failure. The problem is usually caused by an internal infection (endocarditis) or a rheumatic disease.

Inflammation of the heart muscle caused by infection, alcohol or toxic damage also leads to the development of heart failure.

It should be added that in some cases it is impossible to establish the exact cause that caused the deficiency. This condition is called idiopathic heart failure. Diagnosis of heart failure

Using a stethoscope, the doctor listens for unusual sounds in the lungs that occur due to the presence of fluid in the alveoli. The presence of fluid in a particular area of the body can also be detected using x-rays.

The doctor listens for heart murmurs that occur as blood fills and ejects, as well as when the heart valves work.

Blue discoloration of the extremities (cyanosis), often accompanied by chills, indicates insufficient oxygen concentration in the blood and is an important diagnostic sign of heart failure.

Swelling of the limbs is diagnosed by finger pressure. The time required to smooth out the compression area is noted.

To assess heart parameters, techniques such as echocardiogram and radionuclide cardiogram are used.

During cardiac catheterization, a thin tube is inserted through a vein or artery directly into the heart muscle. This procedure allows you to measure the pressure in the chambers of the heart and identify the location of blockage of blood vessels.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) provides a graphical assessment of changes in heart size and rhythm. In addition, using an ECG you can see how effective drug therapy is. What are the body's defenses to combat deficiency?

In cases where an organ or system of the body is unable to cope with its functions, protective mechanisms are activated and other organs or systems take part in solving the problem. The same is observed in the case of heart failure.

Firstly, changes occur in the heart muscle. The chambers of the heart increase in size and work harder to pump more blood to the organs and tissues.

Secondly, the heart rate increases.

Third, a compensatory mechanism called the renin-angiotensin system is activated. When the amount of blood ejected by the heart is reduced and less oxygen reaches the internal organs, the kidneys immediately begin producing a hormone called renin, which allows salt and water excreted in the urine to be retained and returned to the bloodstream. This leads to an increase in the volume of circulating blood and an increase in pressure. The body must make sure that enough oxygen is supplied to the brain and other vital organs. This compensatory mechanism, however, is only effective in the early stages of the disease. The heart turns out to be unable to work at high pressure for many years under conditions of high pressure.

Chronic heart failure in older people

The growth in the population of older age groups and a significant increase in the prevalence of chronic heart failure (CHF) with aging have led to the fact that the majority of patients with this pathology are currently elderly and senile people. In the figurative expression of Michael W. Rich, CHF in the 21st century has become a “cardiogeriatric syndrome” [1].

It is believed that physiological changes in the body during aging may predispose to the development of CHF [1, 2]. Thus, due to a progressive decrease in the number of cardiomyocytes and changes in the connective tissue of the heart muscle (including amyloid accumulation) with age, regardless of the initial level of blood pressure (BP), myocardial stiffness increases and its moderate physiological hypertrophy occurs with the formation of ventricular diastolic dysfunction. And structural changes in the valves (fibrosis and calcification) and disturbances in excitability and conductivity, which occur with a decrease in the number of functioning cells in the sinus node and the conduction system of the heart, can cause a decrease in the systolic function of the myocardium [3, 4]. Of particular importance in the development of CHF during aging are disorders of the excretory function of the kidneys, which lead to a decrease in the excretion of sodium and water and the development of volume overload of the vascular bed [5, 6]. Renal dysfunction is present in 20% of elderly people; at the age of over 80 years, creatinine clearance can decrease to 50 ml/min or more even without concomitant pathology [7].

The most common causes of CHF in older age groups are coronary heart disease (CHD), arterial hypertension (AH), their combination, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) [8–11].

Although the symptoms of CHF and objective examination data in older people are often changed due to age-related changes and comorbid pathology, the diagnostic criteria of the disease for them do not change [4, 12]. However, the identification of concomitant conditions and diseases is of particular importance for the treatment of such patients, since increased exhaustion and rapid breakdown of the body’s compensatory mechanisms during aging can cause functional failure not only of the system that is affected, but also of others, including the ability to influence the clinic and course of heart failure [1, 4]. Abroad, when collecting a patient’s life history, it is recommended to pay special attention to such information as living conditions, data on caregivers, information about the hospitalized person’s reaction to emergency situations, and use specialized questionnaires to identify cognitive impairment [2]. Classic symptoms of congestive systolic CHF, as a rule, appear in the elderly in the late period of the disease. A sharp limitation of physical activity and lifestyle changes during aging lead to a decrease in complaints of shortness of breath and rapid heartbeat [12]. Nonspecific complaints predominate (generalized weakness, fatigue), which are also characteristic of symptoms of physiological aging [4]. In old age, atypical signs of CHF occur: the appearance of cognitive and emotional disorders (episodes of delirium, irritability), sleep changes (both drowsiness and insomnia), decreased appetite [1, 13]. The most sensitive physical sign of heart failure in the elderly is basal crepitus, and the most specific objective sign is increased venous pressure in the jugular vein [12]. Taking into account the low specificity of complaints and the results of clinical examination, data from additional studies are of particular importance for the treatment of elderly patients. The study of natriuretic peptides to confirm and differential diagnosis of CHF (for example, with primary pulmonary symptoms), determine prognosis and monitor the effectiveness of treatment remains mandatory in older people, but it is believed that its informative value (especially in women) decreases with age [14]. Due to the high prevalence of hypothyroidism in the elderly and its effect on the course of CHF, it is considered advisable to determine the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone [9, 11]. Analysis of the results of instrumental methods for diagnosing CHF is often complicated by existing age-related changes and concomitant pathology. The need for additional invasive diagnostic methods to confirm coronary pathology or valvular disorders in people of the older age group with heart failure is determined not by the passport age, but by the individual condition, active life expectancy, benefits and risks associated with the intervention [9, 11].

The goals of treatment of CHF in patients of older age groups remain control of risk factors, reduction of symptoms, improvement of quality of life, reduction of the number of hospitalizations and, if possible, improvement of prognosis [8, 9, 11]. A necessary condition for preventing the progression and decompensation of heart failure is effective therapy for diseases that are etiological factors in the development of CHF. Adequate drug treatment of hypertension and coronary artery disease has been proven to be as effective in reducing symptoms and improving prognosis in older patients as in younger patients [9, 15]. When treating atrial fibrillation, which is a predictor of a high risk of mortality in patients with CHF, heart rate (HR) control is preferable in older patients [16, 17]. Anticoagulant therapy is of particular importance in this case, since the risk of developing thromboembolic complications in elderly patients is more significant [18].

Although data from a 20-year follow-up of 5314 males aged 65–92 years suggest that exercise capacity is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in the elderly, and increasing it increases survival in this population [19], the results Foreign studies with physical training in elderly patients with CHF are contradictory. Most had a favorable result, but there are also reports of no improvement in most indicators (physical exercise tolerance, quality of life, level of neurohormones in the blood, clinical manifestations of CHF). Domestic publications contain data on the effectiveness of physical rehabilitation in patients aged 60 to 84 years with CHF from functional class II to IV according to the criteria of the New York Heart Association (NYHA) in terms of slowing down the processes of myocardial remodeling, increasing tolerance to physical activity and improving the quality of life [20], but do not allow us to draw final conclusions about the tactics for choosing the optimal physical training regimen depending on the patient’s initial condition, concomitant diseases, drug therapy used, place and conditions of the exercises.

General recommendations regarding reducing salt in the diet and controlling the amount of fluid taken in elderly patients with CHF remain. CHF itself can lead to progression of nutritional deficiency, which increases the risk of frailty, immunodeficiency and poor prognosis [21]. Foreign authors draw attention to the unfavorable features of their diet associated with financial restrictions and living conditions of older people, such as more frequent consumption of ready-made and semi-finished products with a high calorie content and a large amount of sodium, which worsens the course of heart failure [7].

There is a limited number of studies on the optimal drug therapy for CHF in older patients (especially 80 years and older), but there is no reason to suggest that their pharmacotherapy should differ from that recommended at a younger age. Of particular importance is taking into account individual characteristics, concomitant pathology and the ability to absorb or tolerate medications.

Thanks to data from large multicenter studies, there is no doubt about the importance of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) in the treatment of CHF in the elderly. Although in a meta-analysis of ACEI trials, survival with active therapy was superior in those aged <60 years, active ACEI therapy at any age had a comparable effect on the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality and hospitalization. Good tolerability of high doses of ACEIs by patients with an average age of 64 and 70 years was demonstrated in the ATLAS and NETWORK studies, but a number of other studies revealed an association with increasing risk of deterioration of renal function when using ACEIs with age, which was clinically manifested by hypotension, azotemia, and gastrointestinal symptoms , hyperkalemia and leukopenia [22]. Therefore, the appointment of ACE inhibitors in the elderly requires: a thorough assessment of renal function, starting therapy with lower doses; slower rates of drug titration; withdrawal, if possible, of vasodilators; monitoring blood pressure levels in a lying, sitting and standing position. The latter is due to the fact that in elderly and senile age, with a combination of age-related changes in blood vessels (decrease in the elasticity of large vessels and an increase in total peripheral resistance due to a decrease in the lumen of small arteries) and neurohumoral regulation (activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and a decrease in the effectiveness of beta-adrenergic stimulation) severe blood pressure lability with orthostatic hypotension occurs [4]. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists, although they have not shown advantages over ACEIs, are better tolerated, which is especially important for increasing compliance in older patients.

The main randomized trials of β-adrenergic blockers in CHF included a significant number of elderly patients. A study of a cohort of almost 12,000 patients (mean age 79 years) showed that their use is associated with a significant reduction in mortality from CHF and mortality from all causes [23]. The benefits of prescribing the retard form of metoprolol, carvedilol and bisoprolol in the elderly were the same as in younger patients. An analysis of the results of the use of the same β-blockers in elderly people in a number of small studies also did not reveal a significant effect of age on reducing mortality and reducing the number of hospitalizations. A rare example of a study specifically examining patients 70 years of age and older with CHF is the SENIORS study. It demonstrated a reduction in all deaths or hospitalizations due to cardiovascular disease, regardless of ejection fraction, during treatment with the β-blocker nebivolol [24]. Thus, the administration of β-blockers is recommended for all patients with CHF, regardless of age. Their use is accompanied by an improvement in long-term survival of patients, and their effectiveness does not depend on the presence or absence of coronary artery disease and hypertension, but is associated with a higher initial heart rate. Concerns about the effects of β-blockers on cognition are based more on anecdotal reports than on rigorous scientific evidence [7].

Although the effect of diuretics on the prognosis of CHF has not been studied in serious placebo-controlled studies, these drugs relieve symptoms of pulmonary or systemic congestion and are widely used in practice. With aging, the effectiveness of some diuretics decreases, for example, the renal clearance of furosemide decreases. In addition, the presence of CHF itself limits the absorption of furosemide and bumetanide. Less is known about the effect of aging and CHF on the outcome of thiazide diuretic therapy. It is believed that the use of diuretics with a physiological decrease in renal function in older people can contribute to an increase in electrolyte disturbances and an exacerbation of age-associated comorbidities [7]. CHF itself significantly aggravates potassium deficiency, which is typical for the elderly due to a reduction in its amount in the diet, a decrease in the efficiency of potassium reabsorption in the kidneys and a decrease in dry body weight, so patients in older age groups are especially prone to hypokalemia [25]. An underappreciated problem in the elderly that is exacerbated by diuretic therapy is urinary retention and incontinence. Risk factors for their development are age and treatment of aging-related comorbidities. A significant proportion of patients with mild or moderate symptoms of incontinence or urinary retention choose not to report it unless the clinician specifically asks about urinary incontinence, preferring to avoid taking diuretics [26]. If there are problems with mobility, diuretic therapy can interfere with the daily activities of older patients, and a pronounced decrease in intravascular volume due to the use of diuretics for predominantly diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle can reduce cardiac output and cause hypotension, to which the elderly are especially sensitive. To reduce the severity of side effects of diuretic therapy in older patients with CHF, it is proposed to divide their dose into several doses or reduce it in case of symptoms of hypoperfusion or an increase in renal failure during titration of doses of neurohormone blockers; avoiding taking diuretics late in the day to avoid nocturia; prescribing the minimum doses of diuretics necessary for stable weight and symptoms during long-term treatment, monitoring renal function and electrolyte balance with each change in therapy.

Although in the RALES study, in elderly patients (mean age 67 years) with advanced heart failure (functional class III–IV, ejection fraction <35%) treated with ACE inhibitors and loop diuretics, low-dose aldosterone antagonist spironolactone reduced mortality by 30%. , the number of hospitalizations for decompensated heart failure by 35% and significantly improved the functional class of CHF, and no cases of hyperkalemia or renal dysfunction were noted even with close monitoring of laboratory parameters over time [27], the results of the study cannot be completely transferred to the population of elderly patients with CHF, since a creatinine level of more than 220 µmol/l or significant concomitant pathology served as criteria for exclusion from the study. Current recommendations for the treatment of heart failure include reducing the initial dose of spironolactone to 12.5 mg/day in older adults with creatinine clearance less than 50 ml/min and refusing to prescribe it if creatinine clearance is less than 30 ml/min. To exclude renal dysfunction and hyperkalemia, patients should be advised to immediately discontinue the drug if diarrhea or other conditions leading to dehydration develop.

Digoxin has long been the mainstay of treatment for congestive heart failure. Although the analysis of data from the DIG trial showed no effect on all-cause mortality, current national and European guidelines recommend its use to control symptoms and reduce hospitalization in severe CHF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction or advanced heart failure. in combination with the tachysystolic form of atrial fibrillation. Patients aged 70 years and older accounted for 27% of the DIG, and treatment benefits were maintained across all age groups. However, age was also an independent risk factor for the development of complications of digoxin therapy (toxicity, hospitalization due to toxicity) [28]. In the elderly, disruption of its excretion quite often occurs, and toxic effects can occur when taking small doses and “normal” levels of digitalis in the blood serum; manifest themselves with typical symptoms of glycoside intoxication (disturbances in heart rhythm and conduction, nausea and vomiting) and atypically (falls, anorexia, depression, confusion). Thus, the administration of digoxin in the elderly requires the use of lower doses of the drug and careful monitoring of symptoms and laboratory parameters of renal function during treatment.

In older patients, CHF is extremely rarely an isolated pathology, more often combined with at least three, and in 25% of patients with six or more concomitant diseases [7]. On average, during hospitalization of elderly people diagnosed with CHF, five more nosological forms are identified [29]. According to foreign sources, most often these are diabetes, chronic renal failure, chronic lung diseases, anemia and depression. According to domestic data, the most common concomitant pathology is: diseases of the musculoskeletal system, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diseases of the gastrointestinal tract [30]. The combination of several nosological forms significantly complicates the process of diagnosis and selection of therapy. Thus, symptoms characteristic of heart failure (shortness of breath, swelling of the legs, or nocturnal orthopnea) may occur with obesity, tachyform atrial fibrillation, coronary insufficiency, hemodynamic disorders with volume overload (for example, in renal failure), or with increased afterload (for example, in hypertensive crisis). Chronic lung diseases change the severity of shortness of breath and tolerance to physical activity. Anemia that occurs in older patients due to chronic diseases (kidney disease, malignant tumors), drug interventions (use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin and other drugs that promote blood loss) or insufficient intake of iron, folic acid, vitamin B1, etc. increases the symptoms of CHF, but is also an independent negative predictor of prognosis [7]. Depressive and anxiety disorders in the elderly increase the number of symptoms, complicate the assessment of complaints, reduce the effectiveness of treatment for CHF and increase the frequency of hospitalizations. In patients hospitalized for CHF, depression is significantly and independently associated with decreased survival [31]. Falls with hip fracture are associated with increased mortality in the elderly, and their risk may increase with standard treatment of CHF due to postural hypotension; cognitive impairment; urinary incontinence. Of additional importance may be changes in the balance of proprioception with age and bradyarrhythmia due to dysfunction of the sinus node (sick sinus syndrome), as well as due to the effects of drugs with negative chronotropic properties (digoxin, β-blockers). Renal failure is associated in patients with CHF with an increased risk of side effects of medications used for treatment, a higher incidence of hospitalization and a poor prognosis. Detection of microalbuminuria alone is already a predictor of an unfavorable prognosis in CHF (increased risk of death by 60–80% and risk of hospitalization due to progression of CHF by 30–70%) [32]. Thus, in older people, combined pathology with CHF can not only present additional difficulties in the management of patients, but also determine their life prognosis. A strategy aimed at timely detection and treatment of concomitant diseases in elderly people with CHF can prevent up to 55% of hospitalizations. At the same time, this inevitably leads to polypharmacy, polytherapy, an increase in the frequency of side effects of medications and unwanted drug interactions. Thus, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs lead to renal sodium and fluid retention, reduce the effectiveness of ACEIs, and can cause heart failure even in patients who are not at increased risk. When combined with diuretics, the risk of hospitalization for CHF in people over 55 years of age doubles, and combined use with spironolactone significantly increases the likelihood of hyperkalemia and renal dysfunction. Nitrates increase the risk of developing postural hypotension in the elderly, can worsen the prognosis for heart defects and do not allow achieving optimal doses of ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers. There are a number of problems associated with drug treatment for depression. Tricyclic antidepressants, by increasing the level of norepinephrine, can provoke the development of arrhythmia and orthostatic hypotension; there is evidence that their use should be avoided in patients with a high risk of developing coronary artery disease or a history of it. Safer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are preferred for CHF, can lead to the development of hyponatremia in the elderly due to the accumulation of serotonin with subsequent stimulation of the production of antidiuretic hormone, and the occurrence of hyponatremia, according to studies, was noted within a week to several months after the onset therapy, therefore, individuals receiving these drugs need to monitor plasma sodium levels over time. Excessive infusion therapy is especially dangerous in elderly patients due to the risk of iatrogenic heart failure, so it is recommended only for clear indications and with careful monitoring of clinical symptoms and hematocrit values.

Thus, the management of patients in the older age group with CHF has a number of features. Their knowledge can help improve treatment results, especially for primary care physicians. However, the most important advice remains that set out in the recommendations of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA): “Of the general measures that should be used in patients with CHF, perhaps the most effective, but yet the least used is careful observation and control” [9].

Literature

- Rich MW Heart failure in the 21st century: a cardiogeriatric syndrome // J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001. Vol. 56, No. 2. P. 88–96.

- Arnold M., Miller F. Congestive Heart Failure in the Elderly [Electronic resource] //? 2002. Available at: https://www.ccs.ca/download/consensus_conference/consensus_conference_archives/2002_05.pdf. [Access date: 02/12/2011].

- Robin AP et al. Heart failure in older patients // Br J Cardiol. 2006. Vol. 13, No. 4. P. 257–266.

- Guide to gerontology and geriatrics. In 4 vols. T. 3. Clinical geriatrics / Ed. V. N. Yarygina, A. S. Melentyeva. M.: GEOTAR-Media. 2007. 894 p.

- Allison SP, Lobo DN Fluid and electrolytes in the elderly // Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004. Vol. 7, No. 1. P. 27–33.

- Chae CU et al. Mild renal insufficiency and risk of congestive heart failure in men and women > or =70 years of age // Am J Cardiol. 2003. Vol. 92, No. 6. P. 682–686.

- Imazio M. et al. Management of heart failure in elderly people // Int J Clin Pract. 2008. Vol. 62, No. 2. P. 270–280.

- National recommendations of VNOK and OSSN for the diagnosis and treatment of CHF (third revision) [Electronic resource]. Access mode: https://medic.ossn.ru/upload/ossn_pdf/Recomend/Guidelines%20SSHF%20rev.3.01%202010.pdf. [Access date: 02/02/2011].

- Hunt SA et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation // J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009. Vol. 53, No. 15. P. 1–90.

- Ahmed A. DEFEAT heart failure: clinical manifestations, diagnostic assessment, and etiology of geriatric heart failure // Heart Fail Clin. 2007. Vol. 3, No. 4. P. 389–402.

- Dickstein K. et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) // Eur J Heart Fail. 2008. Vol. 10, No. 10. P. 933–989.

- Tresch DD Clinical manifestations, diagnostic assessment, and etiology of heart failure in elderly patients // Clin Geriatr Med. 2000. Vol. 16, No. 3. P. 445–456.

- Vogels RL et al. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature // Eur J Heart Fail. 2007. Vol. 9, No. 5. P. 440–449.

- Vaes B. et al. The accuracy of plasma natriuretic peptide levels for diagnosis of cardiac dysfunction and chronic heart failure in community-dwelling elderly: a systematic review // Age and Ageing. 2009. Vol. 38, No. 6. P. 655–662.

- Beckett NS et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older // N Engl J Med. 2008. Vol. 358, No. 18. P. 1887–1898.

- Go AS et al. National Implications for Rhythm Management and Stroke Prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study // JAMA. 2001. Vol. 285, No. 18, pp. 2370–2375.

- Heeringa J. et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study // Eur Heart J. 2006. Vol. 27, No. 8. P. 949–953.

- Man-Son-Hing M., Laupacis A. Anticoagulant-related bleeding in older persons with atrial fibrillation: physicians' fears often unfounded // Arch Intern Med. 2003. Vol. 163, No. 13. P. 1580–1586.

- P. Kokkinos et al. Exercise capacity and mortality in older men: a 20-year follow-up study // Circulation. 2010. Vol. 122, No. 8. P. 790–797.

- Osipova I.V., Efremushkin G.G., Berezenko E.A. Long-term physical training in the complex treatment of elderly patients with chronic heart failure // Heart failure. 2002. No. 5. P. 218–220.

- Persson MD et al. Nutritional status using mini nutritional assessment and subjective global assessment predict mortality in geriatric patients // J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002. Vol. 50, No. 12. P. 1996–2002.

- Garg R., Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials // JAMA. 1995. Vol. 273, No. 18. P. 1450–1456.

- Sin DD, McAlister FA The effects of beta-blockers on morbidity and mortality in a population-based cohort of 11,942 elderly patients with heart failure // Am J Med. 2002. Vol. 113, No. 8. P. 650–656.

- McMurray J., Judge TG, Caird FI Making sense of SENIORS // Eur Heart J. 2005. Vol. 26, No. 3. P. 203–206.

- Macleod CC Nutrition of the elderly at home. III. Intakes of minerals // Age Ageing. 1975. Vol. 4, No. 1. P. 49–57.

- Gillespie ND The diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the older patient // Br Med Bull. 2005. Vol. 75–76, No. 1. P. 49–62.

- Pitt B. et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators // N Engl J Med. 1999. Vol. 341, No. 10. P. 709–717.

- Gheorghiade M., Adams KF Jr., Colucci WS Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders // Circulation. 2004. Vol. 109, No. 24, pp. 2959–2964.

- Braunstein JB et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare benefits with chronic heart failure // J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. Vol. 42, No. 7. P. 1226–1233.

- Sitnikova M. Yu. et al. Features of the clinic, diagnosis and prognosis of chronic heart failure in hospitalized elderly patients // Heart failure. 2005. No. 2. P. 85–87.

- Jiang W. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure // Am Heart J. 2007. Vol. 154, No. 1. P. 102–108.

- Jackson CE et al. Albuminuria in chronic heart failure: prevalence and prognostic importance // Lancet. 2009. Vol. 374, No. 9689. P. 543–550.

E. A. Temnikova, Candidate of Medical Sciences

State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education Omsk State Medical Academy of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Omsk

Contact Information

Treatment of heart failure

For drug therapy of heart failure, the following groups of drugs are used: diuretics, cardiac glycosides, vasodilators (nitrates), calcium channel blockers, beta blockers and others. In particularly severe cases, surgical treatment is performed.

Diuretics have been used since the 50s of the 20th century. The drugs help the heart function by stimulating the excretion of excess salt and water in the urine. As a result, the volume of circulating blood decreases, blood pressure decreases, and blood flow improves.

The most important for heart failure is a group of drugs derived from the digitalis plant or “cardiac glycosides”. These medicinal substances were first discovered in the 18th century and are widely used to this day. Cardiac glycosides affect internal metabolic processes inside heart cells, increasing the force of heart contractions. Thanks to this, blood supply to internal organs significantly improves.

Recently, new classes of drugs, such as vasodilators (vasodilators), have been used to treat heart failure. These drugs primarily affect peripheral arteries, stimulating their dilation. As a result, by facilitating blood flow through the vessels, heart function improves. Vasodilators include nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

In emergency cases, surgical intervention is performed, which is especially necessary when the failure is caused by disorders of the heart valves.

There are situations when the only way to save a patient’s life is a heart transplant.