Description of the drug BRINTELLIX

Vortioxetine is extensively metabolized in the liver, primarily through oxidation catalyzed by CYP2D6 and to a lesser extent by CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C9.

Due to the risk of serotonin syndrome, vortioxetine is contraindicated in combination with irreversible non-selective MAO inhibitors. Vortioxetine can be prescribed no earlier than 14 days after discontinuation of irreversible non-selective MAO inhibitors. Vortioxetine must be discontinued at least 14 days before starting the use of irreversible non-selective MAO inhibitors.

Concomitant use of vortioxetine with reversible selective MAO A inhibitors, such as moclobemide, is contraindicated. If concomitant use is demonstrated to be necessary, the adjunctive drug should be used in minimal doses and with careful clinical monitoring for the occurrence of serotonin syndrome.

Concomitant use of vortioxetine with a weak, reversible, non-selective MAO inhibitor such as linezolid is contraindicated. If concomitant use is demonstrated to be necessary, the adjunctive drug should be used in minimal doses with close clinical monitoring for the occurrence of serotonin syndrome.

Although the risk of serotonin syndrome with concomitant use of vortioxetine and selective MAO B inhibitors is lower than with concomitant use of vortioxetine and selective MAO A inhibitors, the combined use of vortioxetine with irreversible MAO B inhibitors such as selegiline or rasagiline should be used with caution. In case of simultaneous use, the patient should be closely monitored for the occurrence of serotonin syndrome.

Concomitant use of vortioxetine and other drugs with serotonergic effects (for example, tramadol, sumatriptan and other triptans) may lead to the development of serotonin syndrome. Concomitant use of antidepressants with serotonergic effects with drugs containing St. John's wort may lead to an increased incidence of adverse reactions, including serotonin syndrome.

Antidepressants with serotonergic effects may lower the seizure threshold. Concomitant use with drugs that lower the seizure threshold (for example, tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, SNRIs), antipsychotics (phenothiazines, thioxanthenes, butyrophenones), mefloquine, bupropion, tramadol) should be used with caution.

When vortioxetine was administered at a dose of 10 mg/day concomitantly with bupropion (a strong inhibitor of the CYP2D6 isoenzyme) at a dose of 150 mg 2 times/day for 14 days in healthy subjects, vortioxetine exposure increased by 2.3 times.

Adverse reactions were observed more frequently when bupropion was added to current vortioxetine therapy than when vortioxetine was added to current bupropion therapy. Depending on the individual patient's response, when adding a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (e.g., bupropion, quinidine, fluoxetine, paroxetine) to current vortioxetine therapy, consider reducing the dose of vortioxetine.

Adding vortioxetine 6 days after starting the use of ketoconazole at a dose of 400 mg/day (inhibitor of the CYP3A4/5 isoenzymes and P-glycoprotein) or 6 days after starting the use of fluconazole at a dose of 200 mg/day (inhibitor of the CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4/5 isoenzymes ) in healthy subjects, vortioxetine exposure (AUC) increased 1.3-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively. No dose adjustment is required.

There have been no specific studies of the use of vortioxetine concomitantly with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (such as itraconazole, voriconazole, clarithromycin, telithromycin, nefazodone, conivaptan and many HIV protease inhibitors) and CYP2C9 inhibitors (such as fluconazole and amiodarone) in patients with reduced CYP2D6 activity. However, in these patients, such use would be expected to result in greater exposure to vortioxetine than the moderate exposure described above. Taking a single dose of omeprazole 40 mg (CYP2C19 inhibitor) with repeated doses of vortioxetine did not change the pharmacokinetics of the latter in healthy subjects.

When a single dose of vortioxetine 20 mg was administered 10 days after initiation of rifampicin 600 mg/day (a broad-spectrum CYP isoenzyme inducer) in healthy subjects, vortioxetine exposure (AUC) was reduced by 72%. Depending on the individual response of the patient, when adding a strong inducer of broad-spectrum cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (for example, rifampicin, carbamazepine, phenytoin) to current vortioxetine therapy, the possibility of adjusting the dose of vortioxetine should be considered.

Choosing an antidepressant based on effectiveness and tolerability

Summary

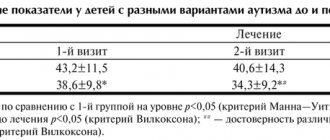

A classification of side effects of antidepressants is presented. Side effects may be toxic or neuronal. Neuronal side effects are divided into “non-therapeutic” (persistent or reversible) and “para-therapeutic” side effects. Seven categories of antidepressant tolerability have been defined. The lowest category VII included clomipramine, imipramine, maprotiline, agomelatine. Category VI includes amitriptyline, V - pipofezin, trazodone, mianserin and mirtazapine, IV - vortioxetine, III - venlafaxine and duloxetine, II - sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and milnacipran, I - pirlindole and moclobemide. Among the most effective antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, venlafaxine in high daily doses), venlafaxine had the best tolerability category. This drug is the most effective and tolerable antidepressant. Other options for the practical use of classifications are discussed.

Summary

A classification of the side effects of antidepressants is presented. Side effects can be toxic or neuronal. Neuronal side effects are divided into “extratherapeutic” (persistent or reversible), as well as “paratherapeutic”. Seven antidepressant tolerance categories have been identified. The lowest category VII included clomipramine, imipramine, maprotiline, agomelatine. Amitriptyline belongs to the VI category, pipofezin, trazodone, mianserin and mirtazapine to the V category, vortioxetine belongs to the IV category, venlafaxine and duloxetine to the III category, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and milnacipran to the II category, and pirlindole and moclobemide to the I category. Among the most effective antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, venlafaxine in high daily doses), venlafaxine was in the best category of tolerance. This drug is the most effective and tolerable antidepressant. Other options for the practical use of classifications are discussed.

The previous article presented a description of the mechanism of action of various antidepressants (tricyclic - TcA, sertonin-modulating - SMA, tetracyclic - CtsA, reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type "A" - OIMAO-A, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors - SSRIs, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – SNRIs, norepinephrine and selective serotonin – NaSSA, melatonergic – MeA, multimodal – MmA) (Table 1).

Table 1. Antidepressants known in Russia, their effect on neurons and the “formula” of the mechanism of action (1-4).

* - white color - the drug does not affect neurons, dark gray - a pronounced increase in activity, light gray - a moderate increase in activity, ** - in high doses, IOR - neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors, SVRR - agents affecting regulatory receptors, OIMAO-A are reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type “A”.

All these drugs, to varying degrees, contribute to the activation of serotonin (↑C or ↑c), norepinephrine (↑H or ↑n), dopamine (↑D or ↑d) or melatonin (↑M or ↑m) neurons, the “tone” of which decreases for depression. But the most pronounced effect on the vital activity of neurons is ↑SNd antidepressants: amitriptyline and imipramine (TcA), as well as venlafaxine (SNRI) in high daily doses. It is no coincidence that many experts consider them to be the most effective drugs for treating depression (5).

Of course, the choice of any antidepressant should be related not only to its therapeutic properties (efficacy), but also to side effects (tolerability). The vast majority of authors agree that tolerability is best with SSRIs and worse with TCAs (6–9), with other drugs falling in between (1). This assessment of the tolerability of antidepressants is correct, but is of a generalized nature. To clarify it, you should refer to data on the mechanisms of side effects.

A minority of them are due to the toxic effect of antidepressants on the organs and tissues of patients. These “toxic” side effects are very dangerous (10). For example, while taking some TCAs (clomipramine, imipramine), as well as MeA (agomelaptine), drug-induced hepatitis is observed, which leads to the death of patients (10, 11). Maprotiline also has serious toxic side effects, causing agranulocytosis and leukopenia (12). Fortunately, toxic side effects are very rare and can be detected promptly by test results.

For example, when it was discovered that agomelatine causes severe and drug-induced hepatitis, detailed precautions were added to its instructions (11). They include a biochemical blood test, which is prescribed to all patients (without exception) before prescribing the drug, as well as while taking it. Similar analysis is required in patients receiving clomipramine and imipramine (13,14). However, when prescribing these antidepressants, biochemical analysis is required only for patients with existing liver diseases. Finally, regular general blood tests to detect agranulocytosis and leukopenia are also necessary during maprotiline treatment (12).

Obviously, the need for additional tests can significantly complicate the use of antidepressants. Fortunately, this is only required when using the medications listed. When prescribing other antidepressants, there is no need to resort to additional examinations. However, their tolerability may be impaired due to the drugs' adverse effects on neurons. As a result, “neural” side effects are formed, which, however, do not directly threaten the lives of patients and are easily diagnosed based on their complaints.

Some of the neuronal side effects are due to the effect of the antidepressant on histamine and acetylcholine neurons, which do not reduce their activity in the formation of mental disorders that are indications for the prescription of antidepressants (2,15). Accordingly, such pharmacological properties can be designated as “non-therapeutic” (extra, unrelated to the treatment process) side effects. They only increase the number of neuronal systems that the patient suffers. Most often, “non-medicinal” side effects are persistent. They may occur throughout the course of treatment, particularly when the antidepressant blocks excitatory receptors on histamine and acetylcholine neurons (15).

This mechanism of action, characteristic of neuroleptics rather than antidepressants, leads to a sharp drop in the activity (inhibition) of these nerve cells (↓G and ↓A) (1,2). Moreover, normal histamine and acetylcholine neurons cannot restore their functions, since there are no effective compensatory mechanisms for this. Accordingly, patients develop persistent mental and somatic symptoms, which seriously complicate treatment (Table 2).

Table 2. The main “non-therapeutic” side effects of antidepressants associated with the blockade of excitatory receptors on histamine and acetylcholine neurons (1,2)

Characterized by drowsiness, fatigue, deterioration of memory and attention. There are complaints of dry mouth, disturbances of accommodation and urination, constipation, pain in the eyes due to increased intraocular pressure, heart rhythm disturbances, increased appetite and weight gain.

There is, however, an antidepressant whose “non-medicinal” side effects are not persistent. This drug is vortioxetine. It does not inhibit histamine and acetylcholine neurons (due to blockade of excitatory receptors), but increases their “tone” due to its influence on regulatory receptors (16). On the one hand, this provides vortioxetine with a unique nature of “non-therapeutic” side effects. In particular, when taking this antidepressant, agitation, anger, “unusual” dreams, and insomnia may occur (Table 3).

Table 3. “Non-medicinal” side effects of vortioxetine (16,17).

Characterized by ketoacidosis, somatic complaints of dizziness, itching (including generalized), sweating, hot flashes, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting. On the other hand, these side effects are fundamentally reversible, since neurons have special mechanisms that are aimed at combating excessive activation. To do this, they can, for example, reduce the sensitivity of their regulatory receptors (a mechanism known as autoregulation). Therefore, “non-therapeutic” side effects of vortioxetine often reduce spontaneously in the first two weeks of treatment (16).

Moving now to the rest of the antidepressants, we point out that the vast majority of them do not have any “non-therapeutic” side effects that increase the number of affected neuronal systems (2). Many drugs do not affect histamine and acetylcholine neurons. Moreover, they increase the activity of only those neurons (serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine) whose “tone” decreases in mental disorders that are indications for the prescription of antidepressants. However, even this feature cannot relieve antidepressants from “neural” side effects. The latter will arise due to the fact that within any affected neuronal system, the activity of only part of the nerve cells decreases, while the functions of the other part are not impaired. Antidepressants both activate “damaged” neurons and create therapeutic effects, and increase the “tone” of normally functioning nerve cells and cause side effects.

At the same time, the tolerability of antidepressants paradoxically turns out to be “hostage” to their therapeutic properties. The more effectively the drug activates the affected neurons, the more it affects similar nerve cells that are still functioning at the proper level. Therefore, it is advisable to designate the side effects under consideration as “paratherapeutic”. They are manifested by restlessness, restlessness, insomnia and anxiety (Table 4).

Table 4. Main “paramedical” side effects of antidepressants (15)

Somatic complaints are represented by sexual dysfunction, disruption of the digestive system and heart rhythm, and fluctuations in blood pressure. As a rule, “paratherapeutic” side effects are reversible. They may resolve on their own in the second or third week of treatment (18). This is due to the already noted above ability of “normal” neurons to quickly adapt to excessive activation, reducing their sensitivity to neurotransmitters (2)2.

The presented data on toxic and neuronal side effects can be used to classify antidepressants into seven tolerability categories, with the seventh being the worst and the first being the best (Table 5).

Table 5. Categories of tolerability of antidepressants, taking into account toxic and neuronal side effects.

Thus, antidepressants from the lowest category VII (clomipramine, imipramine, maprotiline, agomelatine) have toxic side effects that directly threaten the lives of patients. Moreover, when prescribing them, additional examination of patients is required. Problems with tolerability of other antidepressants are due to neuronal side effects. All of them are not fatal, and their identification usually does not require additional examination.

Neuronal side effects are divided into “non-therapeutic” and “para-therapeutic” side effects. The first, as already mentioned above, are associated with “additional” dysfunction of histamine and acetylcholine neurons, which do not reduce their activity in mental disorders that are indications for the prescription of antidepressants. Accordingly, “non-therapeutic” side effects that expand the range of affected neuronal systems determine whether drugs belong to lower tolerability categories (VI, V and IV). In particular, amitriptyline promotes a persistent decrease in the activity of histamine and acetylcholine neurons and is therefore classified as tolerability category VI. “Non-therapeutic” side effects of antidepressants classified as category V are more limited. After all, pipofezin, trazodone, mianserin and mirtazapine contribute to a persistent decrease in the activity of only histamine neurons. Vortioxetine is classified into the next higher tolerability category IV. This antidepressant has the ability to increase the activity of histamine and acetylcholine neurons. However, the associated side effects are often reversible.

The highest tolerability categories I – III include antidepressants that act only on serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neurons, which suffer in mental disorders that are indications for prescribing drugs. These drugs are characterized by “paratherapeutic” side effects that do not increase the number of affected neuronal systems (Table 5). They arise due to the activation of part of the serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neurons, which still maintain normal “tone” (2). At the same time, the severity of “paratherapeutic” side effects depends, first of all, on the ability of the antidepressant to affect serotonin and norepinephrine nerve cells, since they all have a weak effect on dopamine nerve cells (Table 1).

Accordingly, tolerability category III includes antidepressants that simultaneously effectively activate serotonin and norepinephrine neurons. These drugs are venlafaxine and duloxetine (Tables 1 and 5). The first of them, depending on the dose, is a ↑SN- or ↑SNd-antidepressant. As for duloxetine, it has the properties of a ↑CH drug. Category II includes antidepressants that promote pronounced activation of only serotonin or only norepinephrine neurons (Tables 1 and 5). These include all ↑C-antidepressants (sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine), as well as the ↑sND antidepressant – milnacipran. Finally, the highest category I of tolerability is possessed by drugs that are not capable of strongly activating serotonin and norepinephrine neurons (Tables 1 and 5). These are two ↑SND antidepressants - pirlindole and moclobemide.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the presented classification of antidepressants by tolerability does not pretend to be comprehensive. However, it provides clear criteria for assessing the main side effects, which allow different drugs to be compared with each other. This seems to be especially significant in a situation where there are no clear recommendations for taking into account side effects when prescribing antidepressants. For example, a generalized formula is currently used in various publications and instructions. It is recommended that an antidepressant be used “only after a careful assessment of the expected benefits versus risks in patients” (11). But the results of such a “careful assessment” are usually in favor of prescribing the drug.

In particular, about agomelatine they write that if all the requirements of the instructions for prescribing an antidepressant are met, then the risk of developing drug-induced hepatitis becomes minimal (19). At the same time, the unique mechanism of action attributed to agomelatine allows us to state that the benefits of prescribing an antidepressant are much greater than the certain inconveniences that are associated with its hepatotoxicity (19). Meanwhile, the uniqueness of the mechanism of action of agomelatine comes down to the possibility of influencing the neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the neurotransmitter of which is melatonin. And this effect is not at all required for the treatment of depression, since any antidepressant that activates serotonin and norepinephrine neurons can compensate for the deficiency of melatonin activity (20).

The “careful assessment” recommendations presented here are not the only example of facile judgments regarding the tolerability of antidepressants. Some authors believe that side effects are poorly related to the mechanism of action of the drugs. It is argued that side effects are nonspecific, probabilistic and therefore almost unpredictable (18). Other authors are at least looking for the reasons for the formation of side effects in order to take them into account when prescribing antidepressants. Unfortunately, they find these reasons not in the mechanisms of action of the drugs, but in the characteristics of depression, public opinion or the psychology of the patient.

Thus, it is reported that even with the use of any “most easily tolerated drugs in 80% of patients with mild to moderate depression” (21), heterogeneous adverse events are observed. They most often occur in dysthymia, early depressive states, with anxiety and somatic symptoms (21, 22), in people over 45 years of age, with high body weight deficiency (22), and a history of negative placebo reactions (23). It is reported that poor tolerability of antidepressants is associated with patients’ high demands on quality of life (24) and their concerns about social maladjustment (25). An initially negative attitude towards psychiatry on the part of public opinion, the patient’s low awareness of his own illness and the therapy recommended by the doctor, unsatisfactory experience of previous treatment, etc. also contribute to the problem. (22, 26).

The speculative nature of such constructions is obvious. To refute them, it is enough to say that the side effects of drugs, according to the WHO definition, are caused by their pharmacological properties (37). It is difficult to imagine that inhibition of histamine and acetylcholine neurons arises due to the patient’s high demands on quality of life, excessive activation of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neurons due to negative attitudes towards psychiatry from public opinion, and drug-induced hepatitis due to concerns about social maladjustment.

Thus, the presented classification of antidepressants according to tolerability categories allows us to return the study of side effects to the mainstream of biological psychiatry. In addition, this classification is easy to use in practical medicine. In particular, the lower the category of tolerability of an antidepressant, the greater the need for a special justification for its prescription (efficacy, positive experience of treatment in the past, the patient’s desire, etc.). In turn, the appearance of such a detailed justification in the medical history will allow one to avoid many problems (psychological, social and other) that arise during the treatment process between the doctor and his patient.

Using the presented classification, it is easy to resolve the issue of choosing the most effective and tolerable antidepressant. This requires only comparing the tolerability categories of the most effective drugs: amitriptyline (TcA), imipramine (TcA) and venlafaxine (SNRI) (5). The first of them (amitriptyline) belongs to category VI of tolerability (Table 5). The side effects of the second antidepressant (imipramine) are even more serious. This drug belongs to category VII of tolerability. As for venlafaxine, the side effects of this antidepressant are much weaker, and this drug belongs to category III of tolerability. Thus, venlafaxine, when used in high doses, is the most effective and tolerable drug in the treatment of depression.

Venlafaxine is well known in our country under the trade name Velaxin (Egis). This drug has been studied in leading scientific organizations conducting advanced research in the field of psychiatry. Among them are the Federal State Budgetary Institutions “State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry named after V.P. Serbsky" and "Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry" of the Russian Ministry of Health, St. Petersburg Research Institute named after. V.M. Bekhterev (28,29). Long-acting capsules (Velaxin retard) are also well known (30), with the use of which there is a significant reduction in the frequency of such side effects of the drug as nausea (31). In addition, the study of Velaxin was successfully carried out not only in psychiatry, but also in neurology (32).

A video by M.Yu. Drobizhev on the same topic can be viewed at the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwtO_bC_838&t=11s

Bibliography

- Antidepressant therapy and other treatments for depressive disorders. Report of the CINP Working Group based on a review of the evidence. Ed. V.N. Krasnova. M., 2008. – 215 S.

- Stahl SM Stahl's essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical application. — 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2008. - 1117P.

- Drobizhev M. Yu., Fedotova A. V., Kikta S. V., Antokhin E. Yu. Between depression and fibromyalgia: the fate of an antidepressant. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2016;116(4): 114-120. DOI:10.17116/jnevro201611641114-120.,

- Shagiakhmetov F.Sh., Anokhin P.K., Shamakina I.Yu. Vortioxetine: mechanisms of multimodality and clinical effectiveness. Social and Clinical Psychiatry 2016;26(4): 84-96

- Bauer M., Pfennig A., Severus E., Wybrau P.S., J. Angst, Müller H.-U. Clinical guidelines of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry for biological therapy of unipolar depressive disorders. Part 1: Acute and continued treatment of unipolar depressive disorders as of 2013. Modern Therapy of Mental Disorders 2015;4:33-39.).

- Anderson I.M. SSRIS versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Depress. Anxiety. 1998;7(Suppl 1):11-17.

- Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Deakin JF. Evidence based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2000;14:3-20.

- Peretti S, Judge R, Hindmarch I. Safety and tolerance considerations: tricyclic antidepressants vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000; Suppl. 403: 17-25.

- Wilson K, Mottram P, Sivanranthan A, Nightingale A. Antidepressant versus placebo for depressed elderly. 2001. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev. CD000561.) and worse in TsA

- LiverTox. https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov

- Valdoxan - instructions for medical use of the drug. https://medi.ru/instrukciya/valdoksan_5084/

- Ludiomil - official instructions for use. https://medi.ru/instrukciya/lyudiomil_9448/

- Anafranil tablets - instructions (information for specialists) on the use of the drug. https://medi.ru/instrukciya/anafranil-tabletki_8616/

- Melipramine tablets - official instructions for use. https://medi.ru/instrukciya/melipramin-tabletki_4780/

- Drobizhev M.Yu., Ovchinnikov A.A., Kikta S.V. Why do antidepressants have side effects? Pharmateka. 2015. No. 20 (313). pp. 72-77.

- Brintellix. https://www.rlsnet.ru/tn_index_id_87791.htm

- Subeesh V, Singh H, Maheswari E, Beulah E. Novel adverse events of vortioxetine: A disproportionality analysis in USFDA adverse event reporting system database. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017 Dec;30:152-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.09.005.

- Borodin V.I. Tolerability of treatment in patients with depressive disorders (comprehensive analysis). Author's abstract. for the job application ... doc. honey. Sci. Moscow. 2009.

- Freiesleben SD, Furczyk KJ A systematic review of agomelatine-induced liver injury. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 Apr 21;3(1):4. doi:10.1186/s40303-015-0011-7. eCollection 2015.

- Drobizhev M.Yu. Time of meta-analyses and the effectiveness of antidepressants in depression. Social and clinical psychiatry. 2017;4:81-88.

- Aldushin A.A. Prediction of tolerability and refusal of antidepressant therapy based on the analysis of nocebo effects. Russian Psychiatric Journal. 2009; 3:55-61.

- Avedisova A.S., Borodin V.I., Aldushin A.A. Comparison of the effectiveness and tolerability of antidepressants of different groups for mild and moderate depression. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2006;11:15-19.

- Lapin I.P. Personality and medicine. Introduction to the psychology of pharmacotherapy. -SPb.: Dean, 2001.-416С.

- Roberis H. Neurotic patients who terminate their own treatment. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1985; 146 (4):443-445.

- Mosolov S.N., editor. A reference guide to psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacological and antiepileptic drugs approved for use in Russia: 2nd ed. BINOM, Moscow, 2004. - 304C.

- Avedisova A.S., Borodin V.I. Noncompliance or refusal of psychopharmacotherapy? Russian Psychiatric Journal. 2006; 1:61-65.

- https://vmede.org/sait/?id=Farmakologija_klin_farm_y4ebnik_kykes_2009&menu=Farmakologija_klin_farm_y4ebnik_kykes_2009&page=7

- Krasnov V.N., Kryukov V.V. Velaxin® (venlafaxine) in modern treatment of depression: results of the first Russian multicenter study of effectiveness and safety. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. 2007;9 (4), https://www.consilium-medicum.com/magazines/special/psychiatry/article/15426

- Mosolov S.N., Kostyukova E.G., Gorodnichev A.V., Timofeev I.V., Ladyzhensky M.Ya., Serditov O.V. Clinical efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine (Velaxin) in the treatment of moderate and severe depression. Modern therapy of mental disorders. 2007;3:58-63.

- Avedisova A.S., Zakharova K.V., Kanaeva L.S., Vazagaeva T.I., Aldushin A.A.. Comparative study of the effectiveness and tolerability of Velaxin and long-acting Velaxin. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. 2009;11(1):36-40.

- Avedisova A.S. Venlafaxine (Velaxin): results of international studies of a third generation antidepressant. Psychiatrist. and psychopharmacoter. 2006; 11 (2): 2-7.

- Mosolov S.N. Clinical use of modern antidepressants. St. Petersburg, 1995.-565С.).

M.Yu. Drobizhev , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the educational department of the Training Center of the Association of Medical and Pharmaceutical Universities of Russia. Contact Information -

E.Yu. Antokhin , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor, Head of the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of the Orenburg State Medical University of the Russian Ministry of Health.

R.I. Palaeva is an assistant at the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy at the Orenburg State Medical University of the Russian Ministry of Health.

S. V. Kikta , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head. Department of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Polyclinic No. 3" of the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 There are probably side effects due to excessive activation of melatonin nerve cells. However, they are not yet described even in the instructions for agomelatine, a melatonergic drug that has a direct effect on them (11).

2 Theoretically, “para-therapeutic” side effects can be observed even against the background of “non-therapeutic” side effects. After all, any antidepressant activates serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine neurons to varying degrees. However, the drugs are dominated by “non-therapeutic” side effects, if only because they are most often persistent. At the same time, “paratherapeutic” side effects are always reversible. In addition, not all antidepressants that have “non-therapeutic” side effects are capable of seriously activating serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neurons.

BRINTELLIX (tablets)

Vili, but I think it was the deepest.

Everything seemed hopeless, terrible, despair did not leave me, thoughts of suicide were with me constantly. In August he was discharged from the hospital. There was no effect from all the drugs that were prescribed there. And from one drug, the name of which I remembered for the rest of my life, I only got a “high” from the side effects.

A couple of weeks later, on the recommendation of friends, I began visiting another doctor on an outpatient basis. I went to see him for about six months. All this time he selected therapy for me. Over time, very minor improvements appeared, but I really felt progress when I was prescribed “Brintellix”!

I took it in a dosage of only 5 mg (and then weighed about 70 kg) and in combination with “Trittico” (one tablet 150 mg, if I’m not mistaken, I’ve already forgotten). But I had taken Trittico for a couple of months before that with something else - the result was insignificant. And when the drug, the name of which I don’t remember, was replaced with “Brintellix”, progress was immediate. The condition improved very quickly! I can say I have dealt with depression. And this particular drug helped me a lot with this.

Unfortunately, I am still sick. I also had other problems (fears, high fatigue, irritability, I also can’t do mental work - my brain gets tired quickly and my head starts to hurt...). It seems like you can’t call me a psychopath or a schizophrenic... Well, I’m not healthy either. But I finally came out of a deep state of depression, and Brintellix definitely played a significant role in this.

So I definitely recommend it as an antidepressant. Only from him I felt the effectiveness!

But I could only evaluate it as a good drug in the fight against depression. The doctor said that it also helps the brain work, etc., etc. But I only felt its antidepressant work.

There were no side effects. But my dose was minimal. And I have good tolerance to medications. So I cannot guarantee that it is without side effects, so be sure to consult your doctor before taking it. Still, the pill is powerful, and the instructions list a lot of possible side effects.

The only downside is the price. I don’t remember how much it cost, but it was definitely a significant figure. But I took a small dose; one tablet was enough for twenty days. And in order to get out of this terrible state, I was ready to give up my entire salary. I think many will agree with me...

Good health to everyone! May all illnesses pass you by! And I wish everyone to go to the pharmacy... only for “contraceptive items”

I believe that a healthy person is the happiest.