Osgood-Schlatter disease can present as a painful lump in the area below the kneecap during childhood and adolescence as puberty begins. Osgood-Schlatter disease occurs most often in children who participate in sports, especially sports such as running, jumping, or sports that require rapid changes in movement trajectories, such as football, basketball, figure skating and gymnastics.

And although Osgood-Schlatter disease is more common in boys, the gender gap narrows as girls become more involved in sports. Osgood-Schlatter disease affects more adolescents who play sports (by a ratio of one to five). The age range of incidence has a gender factor, as girls experience puberty earlier than boys. Osgood-Schlatter disease usually occurs in boys between 13 and 14 years of age and in girls between 11 and 12 years of age. The disease usually goes away on its own as bone growth stops.

General information

Osgood-Schlatter disease is a specific disease of the musculoskeletal system, namely the knee joints, characterized by dystrophic damage to the tibia in the area of its tuberosity.

Such aseptic destruction of bone tissue occurs against the background of permanent or acute trauma and usually affects only young people at the stage of intensive skeletal development. Clinically, the disease is manifested by swelling of the knee joint, the formation of a kind of growth (bump) under it and pain in its lower part, which occurs during normal physical activity (running, squats, etc.) or even without it.

This pathology was first described in 1878 by the French surgeon O. M. Lannelong under the name “Apophysitis of the tibia,” and in 1903, thanks to the work of the American orthopedist R. B. Osgood and similar works of the Swiss surgeon K. Schlatter (Schlatter), it appeared its more detailed nosography. Wikipedia defines this painful condition with the term “Osteochondropathy of the tibial tuberosity,” and the international classification assigned it the ICD-10 code – M92.5 “Juvenile osteochondrosis of the tibia and fibula.” Despite this, in medical practice this disease is still most often referred to as “Osgood-Schlatter disease” or simply “Schlatter disease”.

Surgical treatment

Surgical intervention is used if, after completion of the ossification process and conservative therapy, a pineal protrusion remains, which causes pain and impairs the function of the joint. Also, an indication for surgery is a cosmetic defect.

The operation consists of fixing bone fragments to the tibial tuberosity if the fragment is large. Or these fragments are deleted.

Removal is performed openly, through a small incision in the area of the tibial tuberosity

In our clinic we use arthroscopic surgical treatment.

Clinical example. Patient M., 34 years old

appearance of the knee before surgery

X-ray before surgery

appearance of the knee joint

before surgery

X-ray after surgery

Advantages of the arthroscopic method of surgery:

- minimal invasiveness of the operation.

- good cosmetic result (the operation is performed through two skin punctures).

- achieving good results in almost 100% of cases.

- minimal number of complications.

- reduction of postoperative rehabilitation period.

The advantages of treating Osgood-Schlatter disease with us:

- diagnosis of the disease is carried out using modern equipment by a highly qualified specialist;

- making an accurate diagnosis, treating this pathology of the knee joint using a conservative or surgical method (using modern arthroscopic equipment);

- complete preoperative and postoperative management;

- preventing the occurrence of complications in the form of inflammation and relapses of the “bump”;

- patient consultation at all stages of treatment and recovery.

Don't waste your time and money! Don't risk your health!

Contact a qualified orthopedist at the first symptoms of the disease. In our clinic we will help you quickly get rid of your illness.

Pathogenesis

The mechanism of occurrence and further development of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome is directly related to the patient’s age and physical activity. According to statistics, in the vast majority of cases, doctors diagnose Schlatter's disease in children and adolescents in the age group from 10 to 18 years, while young people involved in sports suffer from it 5 times more often than their peers leading a passive lifestyle . The same reason for more intense physical activity explains the fact that this osteochondropathy mainly affects boys.

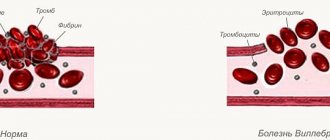

As is known, two large bones are involved in the formation of the human knee joint - the femur (above the knee) and the tibia (below the knee). In the upper part of the last of them there is a special area (tuberosity), to which the quadriceps femoris muscle is attached by means of a tendon. It is this part of the bone that is responsible for its growth in childhood and adolescence and is therefore particularly susceptible to various injuries and damage. During active physical activity, in some cases, the knee joint is subject to a large load and the quadriceps muscle is overstrained, which leads to stretching or tearing of the tendon and a lack of blood supply in this area. As a result of such a traumatic effect and a decrease in nutrition in the area of the tibial tuberosity, gradual necrotic changes develop in it, up to the death of individual parts of its core.

In addition, any injury to the knee joint or constant impact on its musculoskeletal structure (for example, jumping) can cause cracks and microfractures of the tibial tuberosity, which the growing body tries to quickly compensate for by the growth of new connective tissue. As a result of this, a person develops a bone growth (bump), typical of Osgood-Schlatter osteochondropathy, that forms just below the knee. Such a pathological process usually involves one leg, but bilateral involvement of the lower extremities is also possible.

Recommendations

- ^ a b

"Osgood-Schlatter disease".

Whonamedit

. Archived from the original July 12, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2017. - Smith, James; Varacallo, Matthew (November 15, 2021). "Osgood-Schlatter disease." StatPearls. PMID 28723024. Retrieved January 21, 2019. Journal citation required | log = (help)

- ^ a b c d f g gram h i j k l m p o p q r s “

Questions and answers about knee problems.”

www.niams.nih.gov

. 2017-04-05. Archived from the original May 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021. - ^ a b c d

Vaishya, R;

Azizi, A.T.; Agarwal, AK; Vijay, V (13 September 2016). "Tibial tuberosity apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter disease): a review." Cureus

.

8

(9): e780. Doi:10.7759/cureus.780. PMC 5063719. PMID 27752406. - ^ a b

Ferry, Fred F. (2013).

Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2014 e-book: 5 books in 1

. Elsevier Health Sciences. item 804. ISBN 978-0323084314. In the archive from the original dated September 10, 2017. - ^ a b c d

"Osgood-Schlatter disease (knee pain)."

orthoinfo.aaos.org

. May 2015. Archived from the original June 18, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2017. - Circi, E; Atalay, Y; Beyzadeoglu, T. (December 2021). "Treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease: a review of the literature." Musculoskeletal surgery

.

101

(3):195–200. Doi:10.1007/s12306-017-0479-7. PMID 28593576. S2CID 24810215. - Novinsky R.J., Mehlman K.T. (1998). "Decoding the Case History: Osgood-Schlatter Disease." Am J. Orthopedic

.

27

(8):584–5. PMID 9732084. - Atanda A Jr.; Shah, S. A.; O'Brien, K. (February 1, 2011). "Osteochondrosis: common causes of pain in growing bones." American family physician

.

83

(3):285–91. PMID 21302869. - ^ a b

Cakmak, S., Tekin, L., & Akarsu, S. (2014). Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. International Association of Rheumatology, 34(1), 135–136. - ^ a b c

Nakase, J., Aiba, T., Goshima, K., Takahashi, R., Toratani, T., Kosaka, M., Ohashi, Y., and Tsuchiya, H. (2014).

"The relationship between skeletal maturation of the distal patellar tendon insertion and physical characteristics in adolescent male soccer players." Knee surgery, Sports traumatology, Arthroscopy

.

22

(1): 195–199. Doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2353-3. HDL:2297/36490. PMID 23263228. S2CID 15233854.CS1 maint: uses the authors parameter (communication) - Smith, Benjamin (11 January 2021). "Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis." PLOS ONE

.

13

(1):e0190892. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190892. PMC 5764329. PMID 29324820. - Gutman, Jeffrey (April 23, 1996). "Osgood-Schlatter disease." Alfred I. DuPont Institute

. Retrieved February 22, 2021. - "OrthoKids - Osgood-Schlatter Disease."

- Cassas KJ, Cassettari-Wayhs A (2006). "Children's and adolescent sports injuries associated with overexertion." Am Fam Doctor

.

73

(6): 1014–22. PMID 16570735. - Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome

in Who Called It? - Lucena, G. L., Gomes, C. A., Guerro, R. O. (2010). "Prevalence and associated factors of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in a sample of Brazilian adolescents." American Journal of Sports Medicine

.

39

(2):415–420. Doi:10.1177/0363546510383835. PMID 21076014. S2CID 23042732.CS1 maint: multiple names: list of authors (link) - ^ a b

Kabiri, L., Tapley, H., & Tapley, S. (2014).

"Evaluation and conservative treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease: a critical review of the literature." International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation

.

21

(2): 91–96. Doi:10.12968/ijtr.2014.21.2.91.CS1 maint: uses the authors parameter (link) - ^ a b c d e

Gholwe, Pennsylvania;

Scher, D. M.; Khakharia, S; Widmann, RF; Green, D. W. (February 2007). "Osgood-Schlatter syndrome." Current Opinion in Pediatrics

.

19

(1): 44–50. Doi:10.1097/mop.0b013e328013dbea. PMID 17224661. S2CID 37282994. - Peck, D. M. (June 1995). "Apophyseal injuries in a young athlete." American family physician

.

51

(8): 1891–5, 1897–8. PMID 7762480. - Engel A., Windhager R. (1987). "[Importance of the ossicle and therapy for Osgood-Schlatter disease]". Sportverletz Sportschaden

(in German).

1

(2): 100–8. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993701. PMID 3508010. - ^ a b

Gholve PA, Scher DM, Khakharia S, Widmann RF, Green DW (2007).

"Osgood-Schlatter syndrome." Curr.

Opinion. Pediatrician .

19

(1): 44–50. Doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e328013dbea. PMID 17224661. S2CID 37282994. - O. Josh Bloom; Leslie Mackler (February 2004). “What is the best treatment for Osgood-Schlatter disease?” (PDF). Journal of Family Practice

.

53

(2). In the archive (PDF) from the original dated 10/06/2014. - ^ a b

Baltachi H., Ozer V., Tunay B. (2004).

"Rehabilitation of an avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity." Knee surgery, Sports traumatology, Arthroscopy

.

12

(2): 115–118. Doi:10.1007/s00167-003-0383-6. PMID 12910334. S2CID 9338440.CS1 maint: multiple names: list of authors (link) - Kujala WM, Quist M, Heinonen O (1985). “Osgood-Schlatter disease in adolescent athletes. A retrospective study of incidence and duration." Am J Sports Med

.

13

(4): 236–41. Doi:10.1177/036354658501300404. PMID 4025675. S2CID 10484252. - Bloom J (2004). "What is the best treatment for Osgood-Schlatter disease?" Journal of Family Practice

.

53

(2): 153–156. - Yashar A, Loder RT, Hensinger RN (1995). "Determination of skeletal age in children with Osgood-Schlatter disease from radiographs of the knee joint." J Pediatr Orthop

.

15

(3):298–301. Doi:10.1097/01241398-199505000-00006. PMID 7790482. - Vreju F, Ciurea P, Rosu A (December 2010). "Osgood-Schlatter disease - ultrasound diagnosis." Med Ultrason

.

12

(4): 336–9. PMID 21210020. - Lewandowska, Anna; Ratuszek Sadowska, Dorota; Hoffman, Yaroslav; Hoffman, Anetta; Kuchma, Monika; Ostrowska, Iwona; Hagner, Wojciech (07/31/2017). "Incidence of Osgood-Schlatter disease in youth soccer training." Doi:10.5281/ZENODO.970185. Magazine citation required | log = (help)

- ^ a b

Indiran, Venkatraman;

Jagannathan, Deviminal (March 14, 2021). "Osgood–Schlatter disease." New England Journal of Medicine

. Doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1711831. - ^ a b

Nkawi, Mustapha;

El Mehdi, El Alwani (2017). "Osgood-Schlatter disease: disease risk considered trivial." Pan African Medical Journal

.

28

. Doi:10.11604/pamj.2017.28.56.13185. ISSN 1937-8688. - Lucena, Hildacio Lucas de; Gomes, Cristiano dos Santos; Guerra, Ricardo Oliveira (November 12, 2010). "Prevalence and associated factors of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in a sample of Brazilian adolescents":. American Journal of Sports Medicine

. Doi:10.1177/0363546510383835. - ^ a b

de Lucena, Hildacio Lucas;

dos Santos Gomes, Cristiano; Guerra, Ricardo Oliveira (February 2011). "Prevalence and associated factors of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in a sample of Brazilian adolescents." American Journal of Sports Medicine

.

39

(2):415–420. Doi:10.1177/0363546510383835. ISSN 0363-5465. - Ling, Christian Damgaard; Ratleff, Michael Skovdal; Dean, Benjamin John Floyd; Kluzek, Stefan; Holden, Sinead (October 2021). "Current Management Strategies at Osgoode Schlatter: A Cross-Sectional Mixed Methods Study." Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Sports Science

.

30

(10): 1985–1991. Doi:10.1111/sms.13751. ISSN 0905-7188. - Haber, Daniel B.; Tepolt, Francis; McClincy, Michael P.; Kalish, Leslie; Kocher, Mininder S. (07/27/2018). “Fractures of the tibial tubercle in children and adolescents”:. Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine

. Doi:10.1177/2325967118S00134. PMC 6066825. - Guler, Ferhat; Kose, Ozkan; Koparan, Cem; Turan, Adil; Arik, Hassan Onur (September 2013). "Is There a Link Between Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Osgood-Schlatter Disease?" Archives of Orthopedic and Trauma Surgery

.

133

(9):1303–1307. doi:10.1007/s00402-013-1789-3. ISSN 0936-8051.

Classification

In the orthopedic environment, this pathology is usually classified according to the degree of its severity and the severity of the observed external and internal symptoms. Regarding this, there are three degrees of Schlatter’s disease, namely:

- initial – visual manifestations in the form of a lump-like growth under the knee are absent or minimal, pain in the area of the knee joint is episodic, mild and occurs mainly at the time of physical activity on the leg;

- an increase in symptoms - swelling of the soft tissues around the affected knee appears, a lump becomes visually visible directly below it, pain syndrome manifests itself during the period of loads on the leg and for a certain period of time after them;

- chronic - a lump-like formation is clearly visible under the knee, which is most often surrounded by swelling, discomfort and pain in the joint is persistent and is observed even at rest.

Causes

There are two main physical activity-related underlying causes of Osgood-Schlatter disease in adolescents and children:

- direct injuries to the tissues of the knee joint (subluxations and dislocations, sprains, bruises, fractures);

- systematic microtraumas (external and internal) of the knee joint that occur as a result of intense sports or other activities associated with excessive physical stress on the lower extremities.

The greatest risk factors for Schlatter's disease in adolescents and children are:

- football, basketball, handball, hockey, volleyball, tennis;

- track and field athletics, acrobatics, gymnastics;

- judo, kickboxing, sambo;

- skiing, sports tourism, figure skating, cycling;

- ballet, sports and ballroom dancing.

Treatment

Osgood-Schlatter disease usually resolves on its own, and symptoms disappear after bone growth has completed. If the symptoms are severe, then treatment includes medication, physiotherapy, and exercise therapy.

Drug treatment involves prescribing pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, etc.) or ibuprofen. Physiotherapy can reduce inflammation and relieve swelling and pain.

Exercise therapy is necessary to select exercises that stretch the quadriceps muscle and hamstrings, which reduces the load on the area where the patellar tendon attaches to the tibia. Hip strengthening exercises also help stabilize the knee joint.

Symptoms of Osgood-Schlatter disease

The severity of the negative manifestations of this pathology in different patients may differ depending on the nature of the injuries received, the degree of physical activity and the personal characteristics of the body.

At the beginning of the development of the disease, the patient begins to experience vague pain in the knee area, which usually appears after or during physical activity on the affected limb. As a rule, such pain is not yet associated with an internal pathological process and therefore there are quite few visits to the doctor during this period.

Over time, pain symptoms begin to increase, are localized in one place and can appear not only during physical activity, but also at rest. At the same time, swelling caused by edema appears around the affected knee, and a lump-like growth appears just below it. During this period of illness, it becomes increasingly difficult for the patient (especially the athlete) to perform his usual exercises, and sometimes even natural leg movements. The greatest intensity of pain is observed in the body position - kneeling.

Photo of a “bump” in Osgood-Schlatter disease

In addition, the patient may experience other negative symptoms:

- tension in the leg muscles (mainly the thigh muscles);

- limited mobility of the knee joint;

- outbreaks of sharp “shooting” pain in the knee area, arising when it is overstrained;

- severe morning swelling in the upper or lower part of the knee, which forms the day after physical activity.

When you independently palpate the affected knee, points of pain are felt, as well as smoothness of the contours of the tibia. The texture of the knee joint is felt as densely elastic, and a hard lump-like formation is felt under the swollen soft tissues. The general well-being of the patient, despite the accompanying pain and pathological processes in the knee, does not change significantly. The skin over the affected joint does not turn red, temperature indicators remain normal.

In most clinical cases, this disease occurs in a measured chronic form, but sometimes its wave-like course can be observed with periods of sudden exacerbation and relative calm. Without medical intervention and with continued physical activity, negative symptoms can persist for many months and worsen against the background of further mechanical damage to the knee joint. However, the manifestations of the disease gradually disappear on their own over 1-2 years, and by the time the period of bone tissue growth ends (approximately 17-19 years) they usually eliminate themselves. Before treating Osgood-Schlatter, the need for such therapy should be comprehensively and individually assessed, since in some cases it may be inappropriate.

Signs and symptoms

Knee of a Man with Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease causes pain in the anterior lower part of the knee.[9] This is usually where the ligament and bone of the patella and the patellar ligament join. tibial tuberosity.[10] The tibial tuberosity is a slight elevation of bone on the anterior and proximal portion of the tibia. The patella attaches the quadriceps anterior muscle to the tibia through the kneecap.[11]

Severe knee pain usually occurs during activities such as running, jumping, lifting objects, crouching, especially walking up or down stairs and kneeling.[12] The pain intensifies with a sharp blow to the knee. The pain can be reproduced by extending the knee against resistance, straining the quadriceps muscle, or striking the knee. The pain is initially mild and intermittent. In the acute phase, the pain is severe and continuous. The impact on the affected area can be very painful. Bilateral symptoms occur in 20–30% of people.[13]

Tests and diagnostics

In general, the doctor can suspect the development of Schlatter’s disease due to the complexity of the patient’s clinical manifestations and the localization of the pathological process typical for this disease. The gender and age of the patient also play an important role in correct diagnosis, since adults, as a rule, are not exposed to this type of damage. Even through a simple visual examination and the usual collection of anamnesis regarding previous injuries or overloads of the knee joint, an experienced orthopedic traumatologist is able to make the correct diagnosis, but it would be useful to confirm it using some hardware diagnostic methods.

The decisive factor in making an unambiguous diagnosis of Osgood-Schlatter disease in children and adolescents was and remains radiography , which, in order to increase the information content of the pathology, is best carried out over time. To exclude other orthopedic diseases, such an examination of the affected knee joint must be carried out in two projections, namely lateral and direct.

In the initial phase of the development of the disease, X-ray images show a flattening of the tibial tuberosity in its soft part and a rise in the lower edge of the clearing, corresponding to the adipose tissue located in the anterior lobe of the knee joint. The last discrepancy with the norm is caused by an increase in the size of the infrapatellar bursa, which occurs as a result of its aseptic inflammation. There are most often no visible changes in the ossification nucleus itself at this stage of Schlatter’s disease.

X-ray of the knee joint in Osgood-Schlatter disease

As the pathology progresses, the x-ray picture changes for the worse. The photographs show a shift of the ossification nucleus by 2-5 mm upward and forward relative to the standard location of the tuberosity or its fragmentation. In some cases, there may be unevenness of the natural contours and unclear structure of the ossification nucleus, as well as signs of gradual resorption of its parts, but most often it fuses with the main body of the bone with the formation of a bone conglomerate in the form of a spiky protrusion. This “bump”, characteristic of Schlatter’s disease, in the later stages of the disease is especially clearly visible on a lateral radiograph and is clearly palpable during palpation in the area of the tuberosity.

In some atypical cases, it may be necessary to prescribe an MRI , CT and/or ultrasound of the problem knee and adjacent tissues to clarify the expected diagnosis. It is also possible to use a technique such as densitometry , which will provide comprehensive data on the structural state of the bones being studied. Other laboratory diagnostic methods, including PCR studies and blood tests for rheumatoid factor and C-reactive protein, are carried out in order to exclude the possible infectious nature of problems with the knee joint (mainly nonspecific and specific arthritis ).

Differential diagnosis of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome must be carried out with any fractures in the knee joint, bone tuberculosis , patellar tendinitis osteomyelitis , infrapatellar bursitis , Sinding-Larsen-Johanson disease and tumor neoplasms.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms.[15]

Ultrasound echography

This test can see various warning signs that predict whether OSD may occur. Ultrasound ultrasound can determine whether there is tissue swelling and cartilage swelling.[11] The main purpose of ultrasound is to detect OSD early rather than later. It has unique features such as detecting tumor enlargement in the tibia or cartilage surrounding the area and can also see if there is any new bone that is starting to grow around the tibial tuberosity.[ citation needed

]

Types

Three types of avulsion fractures.

OSD can result in an avulsion fracture, with the tibial tuberosity being separated from the tibia (usually remaining connected to the tendon or ligament). This injury is rare because mechanisms exist to prevent damage to strong muscles. A fracture on the tibial tuberosity may be complete or incomplete.[ citation needed

]

Type I: A small fragment is displaced proximally and does not require surgical intervention.[ citation needed

]

Type II: The articular surface of the tibia remains intact and a fracture occurs at the junction of the secondary ossification center and the proximal tibial epiphysis come together (may or may not require surgery).[ citation needed

]

Type III: Complete fracture (through the articular surface), including a high probability of damaging the meniscus. This type of fracture usually requires surgery.[ citation needed

]

Differential diagnosis

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome,[16] is a similar condition involving the patella and the inferior border of the patella bone rather than the superior border of the tibia. Sever's disease is a similar condition affecting the attachment of the Achilles tendon to the heel.[ citation needed

]

Treatment with folk remedies

With the permission of the attending physician and in addition to traditional methods of treating Schlatter's disease, the use of folk remedies is allowed, which mainly boil down to the use of various compresses and rubbing that relieve pain and inflammation. The following recipes have proven themselves well in this direction.

Honey compress

To make such a product, natural fresh honey should be mixed in equal proportions with medical alcohol and heated in a water bath until the honey is completely liquefied. Immediately after this, you need to moisten a clean piece of gauze in this mixture, apply it to the problem joint and wrap it first with cellophane and then with a warm cloth (preferably wool). Such procedures can be carried out twice a day for a month, keeping the compress on the knee for approximately 2 hours.

St. John's wort and yarrow

A kind of ointment is prepared from a crushed mixture of these herbs (in equal proportions), for which they are mixed with rendered pork fat, and then heated over low heat for 15 minutes. After cooling, the ointment is considered ready for use and can be rubbed into the skin around the injured knee 2-3 times a day.

Garlic

Two medium heads of garlic are peeled, passed through a garlic press and mixed with 400 ml of regular apple cider vinegar. Before use, this drug should be infused for a week in a dark glass container, where it can then be stored for six months. The method of application is to rub a small volume of this tincture into the damaged knee area 2-3 times a day.

Burdock

Finely chop a few fresh burdock leaves, place them on clean gauze and wrap it around the painful part of the leg for 3 hours. This dry compress is placed at night and applied once every 24 hours for one month (instead of burdock, you can take cabbage or plantain leaves).

Onion

Grate two small peeled onions on a fine grater and mix them with 1 tsp. granulated sugar. The resulting mixture is used for night compresses for about a month.

Healing oils

Camphor, clove, eucalyptus, menthol oil and aloe juice should be carefully mixed in equal proportions. This mixture should be rubbed into the skin over the damaged area several times a day, and then wrapped with a warm cloth.

Prevention

Prevention of the first occurrence or re-development of Schlatter's disease in general consists of controlling the intensity of physical activity performed by a child or adolescent on the lower extremities, especially if he is actively involved in sports, dancing, etc. This largely depends on the parents, since young people are rarely aware of the adequacy of their own training and can constantly overexert themselves. Also, an important role in the preservation of joints and the entire skeletal system during the period of its growth is played by nutritious nutrition, which should include the entire complex of minerals and vitamins . In addition, it is imperative to undergo full professional treatment for any injuries sustained by children, even if at first glance they seem insignificant.

Osgood-Schlatter disease in adults

The age group at increased risk of developing Schlatter's disease includes only children and adolescents, whose tibia in the area of their tuberosity are in the process of intensive growth. As it stops and the body naturally matures, the tuberosity zone becomes stronger and eventually completely ossifies, which in itself excludes the development of this disease in adults. The only thing that can connect adults with this osteochondropathy is its residual changes in the form of small tubercles under the knees.

Epidemiology

Osgood-Schlatter disease usually occurs in boys and girls aged 9–16 years.[27] coinciding with periods of growth spurts. It occurs more often in boys than girls, with male to female ratios reported to range from 3:1 to 7:1. It has been suggested that the difference is due to boys' greater participation in sports and risk-taking activities than girls.[28]

Osgood-Schlatter disease resolves or is asymptomatic in most cases. One study found that 90% of enrolled patients experienced symptom resolution within 12 to 24 months. Because of this short symptomatic period, the number of people diagnosed in most patients is only a fraction of the true number.[29]

Among adolescents aged 12 to 15 years, the prevalence is 9.8%, with higher rates of 11.4% in males and 8.3% in females.[30][31][32] Bilateral Osgood-Schlatter disease occurs in approximately 20-30% of patients.[30][31]

The main cause of morbidity has been found to be regular exercise and shortening of the rectus femoris muscle in adolescents in the pubertal phase.[33] Indeed, among those who suffer from Osgood-Schlatter disease, 76% of patients have shortening of the rectus femoris muscle.[33] This risk ratio shows the anatomical relationship between the tibial tuberosity and the quadriceps group of muscles that connect through the patella and its ligamentous structures.

In a survey of diagnosed patients, 97% reported pain on palpation over the tibial tuberosity.[34] The high risk ratio among people with this condition and finger pain is likely why the number one diagnostic modality is physical examination rather than imaging as most bone pathologies are diagnosed.

Research shows that Osgood-Schlatter disease also increases the risk of tibial fractures.[35] It is possible that the rapid development of tuberosity and other changes in the proximal knee in those with this condition are responsible for the increased risk.

Because increased activity is a risk factor for developing Osgood-Schlatter disease, there are also studies that may suggest that children and adolescents with ADHD are at higher risk.[36] Increased activity and tibial tuberosity loading would have been higher in the more active population in the 9–16 year age group, but this study was still unsure which ADHD factor was the exact cause of the higher incidence.

Complications and consequences of Osgood-Schlatter

Most often, Osgood-Schlatter disease does not lead to any serious complications in the damaged knee joint and goes away over time with virtually no consequences. Sometimes, at first after treatment, local swelling or minor pain persists in the knee area, which usually occurs after excessive physical exertion.

Also, quite often, in the area of the previously affected lower leg, a formed bone growth remains noticeable, which, as a rule, does not affect the mobility of the knee joint and does not cause a feeling of discomfort both in everyday life and during sports. In rare cases, with severe cases and/or improper treatment of Schlatter's disease, such a bone growth can provoke deformation and displacement of the patella. osteoarthritis as adults and may experience pain when kneeling, as well as aching pain when weather conditions change.

Care

Treatment is usually conservative, with rest, ice, and specific exercises recommended.[19] Simple pain relievers may be used, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) or NSAIDs such as ibuprofen.[20] Symptoms usually disappear when the growth plate closes.[19] Physical therapy is usually recommended after initial symptoms improve to prevent recurrence.[19] Surgery may rarely be used in those who have stopped growing but still have symptoms.[19]

Physiotherapy

Recommended efforts include exercises to improve the strength of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius muscles.[19]

Strengthening or using an orthopedic bandage with forced joint immobilization is rarely required and does not necessarily contribute to a faster resolution of the problem. However, bracing can provide comfort and help reduce pain because it reduces stress on the tibial tubercle.[21]

Surgery

Surgical removal may rarely be necessary in people who have stopped growing.[22] Surgical removal of the bunions usually produces good results, with improvement of symptoms after a few weeks.[23]

Rehabilitation

Straight leg raises help strengthen your quadriceps without having to bend your knees.

The knee should be kept straight, the legs should be raised and lowered slowly, and the repetitions should be performed for three to five seconds. Rehabilitation focuses on muscle strengthening, gait training, and pain control to restore knee function.[24] Non-surgical treatments for less severe symptoms include: strength exercises, stretching to increase range of motion, ice packs, knee tape, knee braces, anti-inflammatories, and electrical stimulation to control inflammation and pain. Quadriceps and hamstring exercises prescribed by rehabilitation specialists restore muscle flexibility and strength.[ citation needed

]

Education and knowledge about stretches and exercises is important. The exercises should be painless and gradually increase in intensity. The patient is given strict instructions on how to perform the exercises at home to avoid injury.[24] Exercises can include leg raises, squats and wall stretches to increase quadriceps and hamstring strength. This helps avoid pain, stress and tension in the muscles, which lead to further injury that impedes healing. Knee orthotics such as patella straps and knee sleeves help reduce traction forces and prevent painful tibial contact by limiting unnecessary movement, providing support, and adding compression to the area of pain. [ citation needed]

]

List of sources

- Abalmasova E.A. Osteochondropathies // Orthopedics and traumatology of childhood. - M., 1983. - P. 385-393.

- Gorodnik A.G., Lantsov V.P. The problem of Osgood Schlatter's disease // Vestn. X-ray Radiol. — 1963.- No. 38.-С14-17.

- Pozharsky V.F., Osteochondropathy of the tibial tuberosity (Osgood Schlatter disease) // Medical assistant Obstetrics.- 1982.- No. 47(9).- P.53.

- Pudovnikov S.P., Tarabykin A.N. “Method of surgical intervention for Osgood-Schlatter disease” // Military Medical Journal 1987. - No. 7. - P. 62.

- Esedov E.M. “Osgood-Schlatter syndrome” in the practice of a therapist // “Clinical Medicine”. - 1990, - No. 1. - P. 109-111.