Cilostazol (Cilostazolum)

The following unwanted effects may sometimes occur when taking cilostazol.

From the circulatory and lymphatic system:

often - hematomas; infrequently - anemia; rarely - prolonged bleeding time, thrombocytosis; single - tendency to bleeding, thrombocytopenia, granulocytopenia, agranulocytosis, leukopenia, pancytopenia, aplastic anemia.

From the immune system:

infrequently - allergic reactions.

From the digestive system and metabolism:

often - edema (peripheral or facial edema); uncommon - hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus; isolated cases - anorexia.

Mental disorders:

infrequently - anxiety.

From the nervous system:

very often - headache; often - dizziness; infrequently - insomnia, unusual dreams; isolated cases - paresis, hypoesthesia.

From the side of the organ of vision:

isolated cases - conjunctivitis.

On the part of the hearing organ:

isolated cases - tinnitus.

From the cardiovascular system:

often - palpitations, tachycardia, angina pectoris, arrhythmia, ventricular extrasystoles; uncommon - myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, loss of consciousness, eye hemorrhage, nosebleeds, gastrointestinal bleeding, unspecified bleeding, orthostatic hypotension; isolated cases - hot flashes, hypertension, hypotension, cerebral hemorrhages, pulmonary hemorrhages, muscle hemorrhages, hemorrhages in the respiratory tract, subcutaneous hemorrhages.

From the respiratory tract:

often - rhinitis, pharyngitis; infrequently - shortness of breath, pneumonia, cough; isolated cases of interstitial pneumonia.

From the gastrointestinal tract:

very often - diarrhea, bowel dysfunction; often - nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, flatulence, abdominal pain; infrequently - gastritis.

From the hepatobiliary system:

isolated cases - hepatitis, liver dysfunction, jaundice.

For the skin and subcutaneous tissues:

often - rash, itching; isolated cases - eczema, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, urticaria.

From the kidneys and urinary tract:

rarely - renal failure, impaired renal function; isolated cases - hematuria, pollakiuria.

General violations:

often - chest pain, asthenia; infrequently - myalgia, chills; isolated cases - hyperthermia, malaise, pain.

Laboratory research:

isolated cases - increased levels of uric acid, urea, creatinine.

An increased incidence of palpitations and peripheral edema was observed when cilostazol was used concomitantly with other vasodilators that can cause reflex tachycardia, such as dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Use of pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication

ON THE. VAULIN

, Ph.D.,

City Clinical Hospital No. 29, Moscow

Obliterating atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities, leading to a decrease in blood flow, occurs in approximately 12% of the population.

The most common manifestation of this pathology is the stage of intermittent claudication. The pain occurs only during certain physical activity and disappears when you stop. Intermittent claudication is detected with a frequency of 6.4-15.5 per 1,000 people over 55 years of age. The article discusses the basic principles of treatment of this pathology. The effectiveness of using the drug pentoxifylline for this purpose has been assessed. Obliterating atherosclerosis of the vessels of the lower extremities and intermittent claudication

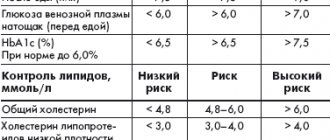

Atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities lead to a narrowing of the lumen of the vessels and thereby to a decrease in blood flow. The prevalence of this pathology is approximately 12% [1]. At the same time, between the ages of 50 and 60 years – 6%, and up to 20% in people over 70 years of age [2]. Up to 2/3 of patients with atherosclerotic vascular lesions of the lower extremities have clinically significant lesions of the coronary arteries, and 30-50% have signs of a stroke on CT/MRI of the brain. On the other hand, risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus contribute to the progression of intermittent claudication.

Intermittent claudication is the most common manifestation of obliterating atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities in the subcompensation stage (stage II according to the Pokrovsky/Fontaine classification), when pain occurs only during a certain physical activity and disappears when stopping. The pain may be aching or cramping, patients may complain of heaviness or weakness in the lower extremities during exercise.

The incidence ranges from 6.4 to 15.5 per 1000 people over 55 years of age [3,4]. Intermittent claudication tends to progress. In addition, at this stage of the disease development, there is a significant 2.5-fold increase in the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality relative to the age-matched population without this pathology [5]. It is no coincidence that all modern recommendations propose to regard intermittent claudication as equivalent to coronary artery disease in terms of the level of risk of coronary events. Additionally, 1 to 3% of patients undergo amputation within 5 years. It is impossible not to note a significant decrease in the quality of life due to the disabling limitation of physical activity and mobility of patients.

Most of the efforts to treat intermittent claudication come from outpatient clinicians. Thus, according to one study, 63% of patients with newly diagnosed intermittent claudication were observed and treated by general practitioners, and only 37% required referral to specialists and hospitalization [6]. Good knowledge of the physician regarding therapeutic options and their effects is the basis for controlling symptoms and preventing the progression of the process. The main goals of treatment for a patient with intermittent claudication are to inhibit or block the development of a pathological process, symptomatic treatment of an existing process, and increase exercise tolerance in order to increase physical activity and quality of life ( Table 1

).

Treatment of a patient with intermittent claudication involves three main components:

1. modification of risk factors (smoking cessation, physical activity, active therapy for concomitant vascular diseases: diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary disease); 2. drug therapy for intermittent claudication, used in case of ineffectiveness of the above measures to reduce symptoms and increase physical activity; 3. Invasive interventions (surgery or endovascular intervention) are usually performed when disabling symptoms develop and the need for them arises in a relatively small—less than 10%—proportion of patients.

Pharmacology of pentoxifylline

A number of medications are used to treat intermittent claudication. Historically, the first agents were vasodilators (such as papaverine), but they failed to demonstrate effectiveness in a number of controlled studies [7] and are now practically not used for this indication.

In the Russian Federation, Pentoxifylline is the most widely used drug, one of the drugs actively used for this condition. The drug is a trisubstituted methylxanthine derivative and has a dose-dependent effect on hemorheological parameters. It reduces blood viscosity, normalizes the ability of red blood cells and leukocytes to deform, thereby facilitating their passage through the capillaries and improving microcirculation and oxygen supply to tissues [8,9]. These data are consistent with the finding that individuals with peripheral atherosclerosis have increased erythrocyte rigidity. It is assumed that the described properties may be due to a decrease in the concentration of fibrinogen in plasma [10]. The antiplatelet effects of pentoxifylline due to the inhibition of phosphodiesterase associated with the platelet membrane have also been described. This leads to accumulation of cyclic AMP levels, inhibition of thromboxane synthesis and increased prostaclin formation [11].

Pentoxifylline is rapidly absorbed after oral administration and binds to blood proteins by 45%. After taking 400 mg tablets, the maximum plasma concentration is reached after 2-4 hours and is 0.3 mg/l. Pentoxifylline undergoes a first-pass effect through the liver. The main metabolites are I and V, the concentration of which after oral administration becomes 5 and 8 times higher than the concentration of the original substance, respectively. The pharmacokinetics of pentoxifylline and its V metabolite are nonlinearly dose dependent. The half-life and area under the concentration-time curve increase with increasing dose [12,13]. The half-life of pentoxifylline itself ranges from 0.4 to 0.8 hours, and that of its metabolites - 1-1.6 hours. The product of biotransformation is metabolite V with the main route of excretion through the kidneys.

| Table 1. Classification of the severity of chronic limb ischemia according to Fontaine, according to A.V. Pokrovsky, according to Rutherford | ||||

| Severity of the current | Classification options | |||

| Fontaine | A.V. Pokrovsky | Rutherford | ||

| Degree | Category | |||

| Asymptomatic | I | I | 0 | 0 |

| Mild intermittent claudication | IIa | IIa (200-1000 m) | I | 1 |

| Moderate intermittent claudication | IIb | IIb (<200 m) | I | 2 |

| Severe intermittent claudication | III | I | 3 | |

| Pain at rest | III | II | 4 | |

| Initial minor trophic disturbances | IV | IV | III | 5 |

| Ulcer or gangrene | IV | 6 | ||

Controlled clinical studies

Unlike clinical studies of antianginal drugs, where during stress tests the most reliable and reproducible indicator is characteristic changes on the ECG, when studying drugs for the treatment of intermittent claudication, one has to be content only with the subjective sensations of patients. Among other things, this indicator has a rather low reproducibility - from day to day the same patient can show significantly different results.

In part, these considerations can explain some of the contradictions in the results obtained [14,15,16,17].

Among the drugs used for intermittent claudication in the Russian Federation, pentoxifylline is perhaps the most studied. In a number of placebo-controlled studies, pentoxifylline prescribed for the treatment of intermittent claudication increased total walking distance. However, in fairness, it should be noted that there were studies without positive results. The main endpoints in the studies described were pain-free walking distance (PDW) and maximum walking distance (MDD) that a patient can walk in a certain period of time. Significant differences in the results of the studies may be explained by the small number of observations, wide variation in endpoint methods, problems with data on smoking and duration of symptoms before study entry [18].

Ernst et al conducted a randomized, double-blind trial in 40 patients to evaluate the effectiveness of pentoxifylline 1,200 mg/day on DBC and IVD compared with placebo [19]. Both groups engaged in therapeutic physical training (walking for 1 hour, 2 times a week). In addition to functional indicators, blood viscosity was assessed using a rotational viscometer. After 1 and 8 weeks, the mean MTD was significantly greater in the pentoxifylline group (409 m) than in the placebo group (293 m). However, after 12 weeks this indicator was not significantly different. There were no significant differences in DBC at any stage. Significant differences in blood viscosity in favor of pentoxifylline were noted after 12 weeks of therapy: 5.18 mPa versus 5.74 mPa in the placebo group (p=0.006). The results obtained allowed the researchers to conclude that pentoxifylline is effective when used in combination with physical training in patients with intermittent claudication.

The efficacy and safety of pentoxifylline in the treatment of patients with intermittent claudication was studied by Porter et al in a placebo-controlled, parallel-group study involving 128 patients [20]. Primary endpoints were DBH and MTD as measured by a standard treadmill test. Pentoxifylline was prescribed in doses ranging from 600 to 1200 mg/day. The treadmill test was performed every 2 weeks. 24 weeks after inclusion in the study, pentoxifylline was significantly more effective than placebo: the mean values of DBC and MTD in the intervention group were 179 and 247 m, respectively, and in the placebo group - 158 and 229 m (p = 0.016 and 0.035, respectively, for differences between groups) . Pentoxifylline was well tolerated. Adverse events were reported in 37 of 67 patients (55%) in the intervention group and 24 of 61 (39%) in the placebo group. The most common complaint was nausea: 24 in the pentoxifylline group versus 3 in the placebo group (p < 0.05).

Lindgarde et al conducted a multicenter placebo-controlled study on 150 patients with intermittent claudication.[21] For 12 months, patients received 1200 mg of pentoxifylline or placebo. To ensure that the disease was stable, the design included a run-in phase where all patients were given placebo for 4 to 6 weeks. As in previous work, effectiveness was assessed by DBC and MTD. The diagnosis of atherosclerotic vascular lesions of the lower extremities was based on the clinical picture, angiography data, as well as non-invasive ultrasonography before and after physical activity. The study included patients diagnosed with the disease more than 1 year ago, with a brachial-ankle index less than 0.8 at rest. As a result, a small but significant increase in IVD after 16-24 weeks of therapy was noted in the group receiving pentoxifylline (the proportion of increase in distance relative to the initial level was 31% versus 9% in the control group, p = 0.023). In terms of tolerability and side effects, no significant differences were noted.

In a placebo-controlled, six-month study, Roekaerts and Deleers, with a rather complex design, assessed the efficacy and safety of pentoxifylline at a dose of 1200 mg/d (in three doses) in 36 patients with intermittent claudication [22]. The study involved 2 phases - the first crossover (n = 20) and the second - in parallel groups (n = 16). The end points were MTD, DBH, as well as subjective assessment of mobility by the patients themselves on a 5-point scale. After 6 months, in the group receiving pentoxifylline, there was a significant increase in DBC and IVD both in relation to the initial level (by 124% and 101%, respectively) (p < 0.05) and in relation to changes in the comparison group (28 % and 9%, insignificant compared to the initial level). When filling out questionnaires, 24 out of 36 patients during pentoxifylline therapy noted an improvement versus 7 patients in the control group. In addition, in the pentoxifylline group there were significantly fewer complaints of pain at rest, muscle cramps, and paresthesia. The authors also noted that the drug was well tolerated.

In a placebo-controlled crossover study, Di Perri and Guerrini studied the effects of pentoxifylline in 24 patients (12 in each group) with Fontan stage II lower extremity vascular disease [23]. Each group participated in one of two treatment periods: pentoxifylline (1200 mg/d in three doses) or placebo for 8 weeks, followed by a 2-week washout phase, after which the groups switched treatments. The primary endpoint was DBH, and walking speed was set using a metronome at 120 steps per minute. In both groups taking pentoxifylline, there was a significant increase of 60% (p < 0.01) in the distance walked without pain. No significant differences were found in the placebo groups. No adverse events were recorded.

However, as mentioned above, a number of studies have failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of pentoxifylline in patients with intermittent claudication, or it was effective only in selected patients. Thus, in the work of Green and McNamara [24], 130 people with intermittent claudication received 1200 mg/d of pentoxifylline 9 for 9 months. The primary endpoint of claudication symptom severity and assessment of the impact of claudication on lifestyle did not significantly improve in 88 of 124 (71%) patients. Only 13 (10%) showed improvement in symptoms in the first 2-3 months of therapy, after which the effect disappeared. However, there was no correlation between the initial severity of the disease and the effectiveness of the drug.

Meta-analyses

Given the inconsistency of data obtained from small randomized trials, several meta-analyses have been conducted.

Thus, in an analysis of 11 randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials [25], it was shown that pentoxifylline leads to a statistically significant increase in DBC (by an average of 29.4 m; 95% CI 13.0–45.9 m] and to an increase in IVD ( 48.4 m; 95% CI 18.3–78.6 m) Based on the results of the study, the researchers concluded that pentoxifylline improved the walking tolerance of patients with moderate symptoms.

The 2011 Cochrane meta-analysis [26] aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of pentoxifylline on physical activity in patients with intermittent claudication. MTD and DBH were assessed. All controlled clinical trials in which [27] either a placebo or another comparator drug were used as a control were selected for analysis. Data were processed from 2816 patients from 23 studies, the results of which were published by the beginning of 2011. The total distance that patients could walk without stopping was greater in the pentoxifylline group compared with placebo; the range of values ranged from 1.2% to 155% in favor of pentoxifylline. The differences in pain-free walking distance were more significant and ranged from 33% to 73% relative to placebo. The authors themselves associated this with the high heterogeneity of the initial data - the differences between patients in different studies, both in initial indicators and in drug use regimens, turned out to be very significant. This did not allow for a reliability analysis. However, based on the accumulated data, the good tolerability of the drug, the authors indicated the effectiveness of the use of pentoxifylline in combination with other interventions for intermittent claudication, including therapeutic lifestyle changes and effects on risk factors. In addition, the authors emphasize that interindividual differences require an individual approach in assessing effectiveness.

Safety and Tolerability

Pentoxifylline is generally well tolerated. Of the adverse events, gastrointestinal (diarrhea, dyspepsia, nausea) and disorders of the central nervous system (headache, dizziness) are somewhat more common. Hypotension and edema are less common. Clinical studies with pentoxifylline were conducted with extended-release tablets and immediate-release capsules (available for clinical studies only). Adverse events were more often observed when taking capsules.[28] There is evidence of increased bleeding and/or an increase in prothrombin time in patients taking pentoxifylline concomitantly with anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. Although a causal relationship with pentoxifylline has not been established, it is recommended to more carefully monitor hemostatic parameters (INR, hemoglobin level, hematocrit) in patients receiving anticoagulants, including warfarin, or in persons at high risk of bleeding (for example, after surgery). [29]. Since pentoxifylline is a methylxanthine derivative, patients concomitantly taking theophylline-containing drugs should be monitored for signs of theophylline intoxication.

Dosage

Pentoxifylline is prescribed for a number of vascular diseases, including obliterating atherosclerosis of the vessels of the lower extremities, cerebrovascular lesions and others [30]. The recommended dosage for intermittent claudication is 1200 mg/day. From this point of view, it is more convenient to use retardated forms of pentoxifylline—Vazonit (600 mg 2 times/day). In the Russian Federation, this is currently the only pentoxifylline in this dosage. Although the effect begins to appear after 2-4 weeks, it is recommended to continue therapy for at least 8 weeks in a row. Clinically significant effects have been shown to persist over 6 months in studies [31,32]. The only published work on the use of Vasonit in patients with intermittent claudication in 20 vascular departments in Russia included 373 patients. Vazonit-retard® was prescribed openly on an outpatient basis, 1 tablet (600 mg) 2 times a day (1200 mg per day) for 2 months [26]. Indications for the use of Vazonit-retard® were:

• the patient has intermittent claudication (limb ischemia grades IIA and IIB), without limitation of walking due to the heart; • ineffectiveness (according to the patient) of previous conservative therapy with pentoxifylline (trental, agapurine and pentoxifylline).

The main results of the study are presented in Table 2

.

| Table 2. Dynamics of some indicators during treatment with Vazonit-retard® in a multicenter study (Pokrovsky et al. 2003) | |||

| Index | Originally | After 1 month of treatment | After 2 months of treatment |

| Pain-free walking distance, m | 219,7 + 16,8 | 353,7 + 24, 9 | 472,1 + 34, 1 |

| Maximum travel distance, m | 308,0 ± 20,2 | 487,7 ± 30, 3 | 611,14 ± 38,7 |

| Pain intensity scale (mm) | 64,2 ± 1,34 | — | 39,74 ± 1,2 |

There were no complications leading to discontinuation of the drug.

Side effects in the form of nausea and a pronounced “rush” to the head were noted in less than 2% of patients in both groups. Moreover, these side effects were observed, as a rule, at the beginning of treatment. Based on the results of the study, the authors concluded that Vazonit-retard® is an effective treatment drug for patients suffering from intermittent claudication. Its side effects develop in less than 2% of cases and do not lead to discontinuation of the drug. It can be recommended for widespread use in patients with intermittent claudication and obliterating diseases of the arteries of the lower extremities. It is necessary to note another very important advantage of the drug Vazonit-retard®, which is positively reviewed by almost all patients who received it; it is taken twice a day, in contrast to the three times taken of Trental 400 or Agapurin 400. In case of poor tolerability, the dose of the drug can be increased gradually to the target 1200 mg/day.

In national guidelines, pentoxifylline is included in the pharmacotherapy of intermittent claudication (Class IIB) as one of the main drugs for increasing IVD (Evidence level A). In the absence of cilostazol in the Russian Federation, pentoxifylline can be considered as one of the main drugs for the treatment of patients with intermittent claudication [33].

Despite the effect, we must not forget that the use of pentoxifylline provides symptomatic relief and does not affect the cause of the disease. The main thing in the treatment of patients with intermittent claudication remains the modification of risk factors: smoking cessation, control of sugar levels in diabetes, lipid-lowering therapy, blood pressure control, use of antiplatelet agents. These measures can not only limit the progression of intermittent claudication, but also reduce the global risk of cardiovascular complications of atherosclerosis, morbidity and mortality. In addition, we must not forget about the benefits of physical training (walking), preferably on a daily basis.

Pentoxifylline is recommended for use after the initiation of therapeutic lifestyle changes and the prescription of the above drugs. If they are ineffective (insufficiently effective), the addition of pentoxifylline is recommended.

Despite the fact that the increase in the distance that patients can walk may not be very large, as a rule, the quality of life of patients increases significantly.

Another effective and proven remedy for the symptoms of intermittent claudication is cilostazol, but this drug is not registered in the Russian Federation.

Promising developments include gene therapy that activates angiogenesis, but so far this intervention has not been well studied [33].

Conclusion

Intermittent claudication is a common disabling symptom due to atherosclerotic vascular lesions of the lower extremities, requiring an integrated approach: measures for therapeutic lifestyle changes, including physical activity, therapy aimed at modifying risk factors (statins, ACE inhibitors, antiplatelet agents.) and therapy aimed at reduction of symptoms and improvement of quality of life. This group includes pentoxifylline (Vazonit). The drug Vazonit is a prolonged form of pentoxifylline, which, when used twice (1 tablet - 600 mg), allows you to maintain the therapeutic dosage of the active substance throughout the day without overnight breaks in therapy. The dosage of pentoxifylline 1200 mg per day is considered optimal. The use of other, non-extended-release forms of pentoxifylline requires more complex dosage regimens, which may be inconvenient for patients.

LITERATURE

1.HIATT WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:1608e1621. 2. Gillings DB. Pentoxifylline and intermittent claudication: review of clinical trials and cost effectiveness analyses. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995; 25(suppl 2): S44-50. 3. Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG, Whiteman M, Dunbar J, Housley E, et al. Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. International Journal of Epidemiology 1996; 25(6): 1172–81. 4. Meijer WT, Cost B, Bernsen RM, Hoes AW. Incidence and management of intermittent claudication in primary care in The Netherlands. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 2002; 20(1): 33–4. 5. Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S. The natural history of claudication: risk to life and limb. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 1999; 12(2): 123–37. 6. Meijer WT, Cost B, Bernsen RM, Hoes AW. Incidence and management of intermittent claudication in primary care in The Netherlands. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 2002; 20(1): 33–4. 7. Coffman JD. Vasodilator drugs in peripheral vascular disease. N Engl J Med 1979; 300: 713-7. 8. Trental (pentoxifylline) product information. Kansas City, MO: Hoechst Marion Roussel. 9.Jan; Dawson, DL, Cutler BS, Meissner MH et al. Cilostazol has beneficial effects in treatment of intermittent claudication. Circulation. 1998; 98: 678-86. 10. Ward A, Clissold SP. Pentoxifylline: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1987; 34: 50-97. 11. Samlaska CP, Winfield EA. Pentoxifyline. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 30: 603-21. 12. Trental (pentoxifylline) product information. Kansas City, MO: Hoechst Marion Roussel. 13. Jan.; Yoshitomi Y, Kojima S, Sugi T et al. Antiplatelet treatment with cilostazol after stent implantation. Heart. 1999; 80: 393-6. 14. Girolami A, Büller HR. Treatment of intermittent claudication with physical training, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline, or nafronyl: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:337–45. 15. Hood SC, Moher D, Barber GG. Management of intermittent claudication with pentoxifylline: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ 1996; 155:1053–9. 16. Ernst E. Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication: a critical review. Angiology 1994; 45: 339–45. 17. Radack K, Wyderski RJ. Conservative management of intermittent claudication. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:135–46. 18. Ward A, Clissold SP. Pentoxifylline: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1987; 34: 50-97. 19. Ernst E, Kollar L, Resch KL. Does pentoxifylline prolong the walking distance in exercised claudicants? A placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Angiology. 1992; 43: 121-5. 20. Porter JM, Cutler BS, Lee BY et al. Pentoxifylline efficacy in the treatment of intermittent claudication: multicenter controlled double-blind trial with objective assessment of chronic occlusive arterial disease patients. Am Heart J. 1982; 104: 66-72. 21. Lindgarde F, Jelnes R, Bjorkman H et al. Conservative drug treatment in patients with moderately severe chronic occlusive peripheral arterial disease. Scandinavian Study Group. Circulation. 1989; 80: 1549-56. 22. Roekaerts F, Deleers L. Trental 400 in the treatment of intermittent claudication: results of long-term, placebo-controlled administration. Angiology. 1984; 35: 396-406. 23. Di Perri T, Guerrini M. Placebo controlled double blind study with pentoxifylline of walking performance in patients with intermittent claudication. Angiology. 1983; 34:40-5. 24. Green RM, McNamara J. The effects of pentoxifylline on patients with intermittent claudication. J Vase Surg. 1988; 7: 356-62. 25. Hood SC, Moher D, Barber GG. Management of intermittent claudication with pentoxifylline: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Can Med Assoc J 1996; 155: 1053-9. 26. Pokrovsky A.V., Kalinin A.A., Chupin A.V., Zamsky K.S., Kolosov R.V., Markosyan A.A. Vasonite retard in the treatment of patients with intermittent claudication due to obliterating diseases of the arteries of the lower extremities. Angiology and Vascular Surgery. 2003. T. 9. No. 2. P. 19. 27. Salhiyyah K, Senanayake E, Abdel-Hadi M, Booth A, Michaels JA. Pentoxifylline for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005262. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005262.pub2. 28. Trental (pentoxifylline) product information. Kansas City, MO: Hoechst Marion Roussel. 29. Trental (pentoxifylline) product information. Kansas City, MO: Hoechst Marion Roussel; 1998 Jan. thirty.

30. Ward A, Clissold SP.

Pentoxifylline: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1987; 34: 50-97. 31. Trental (pentoxifylline) product information. Kansas City, MO: Hoechst Marion Roussel; 1998. 32. Jan., Yoshitomi Y, Kojima S, Sugi T et al. Antiplatelet treatment with cilostazol after stent implantation. Heart. 1999; 80: 393-6. 33. National recommendations for the management of patients with pathology of the arteries of the lower extremities: angiology and vascular surgery. Application. 2013. T. 19, no. 2. pp. 1–67. Source: Medical Council, No. 4, 2015