E.B.Avalueva1, T.V.Adasheva2, A.R.Babaeva3, E.G.Burdina4, N.V.Kireeva5, L.G.Lenskaya6, M.A.Osadchuk5, I.G.Pakhomova1, L. I. Popova7, E.I. Tkachenko1, Yu.P. Uspensky8, Yu.G. Shvarts9, A.A. Myslivets10, E.N. Andrianova10 1North-Western State Medical University. I.I. Mechnikov, Ministry of Health of Russia, St. Petersburg; 2GBOU VPO MGMSU im. A.I. Evdokimov, Ministry of Health of Russia; 3GBOU VPO Volgograd State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 4FGBU Polyclinic No. 3 of the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation, Moscow; 5GBOU VPO First Moscow State Medical University named after. I.M. Sechenov, Ministry of Health of Russia; 6OGAUZ Tomsk Regional Clinical Hospital; 7OrKli Hospital LLC, St. Petersburg; 8City Center for Intestinal Diseases and Endoecology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, St. Petersburg; 9GBOU VPO Saratov State Medical University named after. V.I. Razumovsky, Ministry of Health of Russia; 10OOO NPF Materia Medica Holding, Moscow

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort in combination with bowel dysfunction in the absence of an identifiable organic cause [1–4].

Its frequency in Western countries is about 20%; up to 40% of patients are in the most active working age—30–50 years [2–4]. Women get sick 2 times more often than men [4]. The quality of life and work ability of people suffering from IBS are reduced, and they often behave like patients with a severe organic disease with a satisfactory general condition and no signs of disease progression during follow-up [9].

The pathophysiological basis of IBS consists of disorders of the motor and sensory functions of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), subclinical inflammatory changes, a disturbed intestinal microbiome and psychophysiological disorders associated with visceral ones [1, 3–6]. The condition for the formation of visceral hypersensitivity is the influence of “sensitizing” factors, among which are intestinal infections, psychosocial stress, physical trauma, one way or another associated with abdominal pain [1, 7–9].

In recent years, it has been shown that the trigger in the onset of IBS, as a rule, is stress, which causes the appearance of excessive emotions. Under stress conditions, a neuropeptide (substance P) is activated, which promotes the appearance of minimal inflammatory changes in the colon mucosa (COTC). Inflammation is believed to play a major role in the formation of post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS). It has been proven that the inflammatory process after an intestinal infection can persist for a long time, localized in the somatic lymph nodes and neighboring lymph nodes. In the pathogenesis of inflammation in PI-IBS, hyperplasia and hyperfunction of mast cells and activation of monocytes, which induce the development of immune inflammation, play a significant role [10]. In patients with IBS, there is an increase in the expression of inducible NO synthase, interleukin-1, in the STC, which can also initiate the inflammatory process. It has been established that the development of any type of IBS is associated with hyperplasia of enterochromaffin cells producing serotonin, melatonin, as well as with high expression of peptide YY, infiltration of SOTC by various inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells). At the same time, the activity of the inflammatory process in the STC in patients with IBS was confirmed by the detection of a high number of cells immunopositive to the main marker of inflammation - calprotectin [11].

Clinical manifestations of visceral hypersensitivity are symptoms of hyperalgesia and allodynia (a dysfunction caused by painful stimuli). It has been proven that in IBS, the process of descending suppression of pain perception is impaired, i.e. there is central antinociceptive dysfunction, the pain threshold is 3 times lower than in healthy individuals [3]. Visceral hyperalgesia, which is regarded as a marker of IBS, manifests itself in the form of increased sensitivity to painful stimuli and the sensation of pain, which is caused by non-painful stimuli; the symptoms of IBS, namely flatulence, impaired motility, transit and defecation, are considered secondary, caused by the pain syndrome.

There are no specific symptoms of IBS [2, 3]. A distinctive feature of IBS is the variety of complaints - both gastroenterological and non-gastroenterological (cardiac, respiratory, asthenic, cephalgic, etc.), as well as the presence of psychoneurological disorders [12]. IBS is characterized by the presence of abdominal pain in combination with diarrhea or constipation [3, 4, 13]. Abdominal pain can be of varying intensity and is usually localized in the lower abdomen, although it can also be observed in other parts of the abdomen. It often intensifies after a diet violation, with a surge of emotions, against the background of nervous and physical fatigue. The pain usually decreases after defecation or the passage of gas and does not bother you at night. Along with pain, patients often note changes in the frequency of stool (more than 3 times a day and less than 3 times a week), the shape and consistency of stool, and the appearance of mucus in the stool. A long course of the disease and resistance to treatment with gastroenterological drugs is considered typical [2, 4, 7, 14].

Attempts that have continued to date to develop an effective long-acting treatment regimen for IBS have not yielded results for any variant of the course of the disease. Obviously, this is due to the fact that the problem of searching for and objectively assessing the effectiveness of a particular drug is difficult due to the complexity and lack of understanding of the pathophysiology of IBS and the fairly high placebo effect in this group of patients [2, 4, 13].

A new approach in the treatment of IBS is the use of the complex release-active drug Kolofort, created on the basis of antibodies to human tumor necrosis factor a (anti-TNF-a), brain-specific protein S-100 (anti-S100) and histamine (anti-H). The combination of three active components makes it possible to influence the central and peripheral links in the pathogenesis of functional intestinal disorders, including visceral hypersensitivity, helps reduce the severity of abdominal pain syndrome and restore impaired gastrointestinal motility. Previous preclinical and clinical studies have shown the effectiveness and safety of Kolofort and its components in the treatment of gastrointestinal pathologies of inflammatory and functional origin, as well as in the relief of somatoform dysfunctions and neuropsychiatric disorders against the background of somatic and neurological diseases [15–18].

Of undoubted interest for many specialists are the results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial, which was conducted to show the clinical effectiveness and safety of Kolofort in the treatment of patients with IBS under double-blind placebo control.

Material and methods

The study involved 128 patients (33 men and 95 women) aged 19–59 years (mean age 36.8±12.1 years), and most of the participants were in the most active and working age from 25 to 45 years, which is typical for IBS. All patients had clinical symptoms characteristic of IBS; this diagnosis was verified in accordance with the Rome III criteria (2006) and excluded the presence of structural or biochemical abnormalities in the intestine, which was confirmed by a comprehensive instrumental and laboratory examination. The study involved patients with three variants (subtypes) of IBS. In accordance with the Rome III criteria and the Bristol Stool Shape Scale, patients in the diarrhea-predominant IBS subgroup had pasty (type 6) or watery (type 7) stool in more than 25% of the total number of bowel movements, but the presence of solid (1 type 2) or lumpy (type 2) stool with less than 25% of the total number of bowel movements. Participants in the constipation-predominant IBS subgroup had hard (type 1) or lumpy (type 2) stools in more than 25% of their total bowel movements, but were allowed to have mushy (type 6) or watery (type 7) stools. type) feces with less than 25% of the total number of bowel movements. In patients with mixed IBS, hard or lumpy stool alternated with mushy or watery stool in 25% or more of the total number of bowel movements. Patients with a possible 4th “unclassified” type of IBS, in which deviations in stool consistency are insufficiently pronounced for the specified types, did not participate in the study.

The patient was not included in the study if he had decompensated chronic diseases, onset of IBS symptoms after 50 years of age, detection of pathogenic microflora in the intestines at the time of inclusion in the study, any history of laparoscopic and laparotomic surgical interventions, other gastrointestinal diseases, including celiac disease, cancer, active tuberculosis , viral hepatitis B or C, HIV infection.

In accordance with modern recommendations for assessing the effectiveness of drugs for the treatment of IBS, changes in the intensity of abdominal pain (a biological marker of IBS) were analyzed as a primary criterion [6, 19]. The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with a 30% or greater reduction in pain/discomfort after 4 and 12 weeks of treatment. The secondary effectiveness criteria were assessed:

- the percentage of patients in the IBS subgroup with a predominance of diarrhea with a change in stool type on the Bristol scale to 5 or less (on average per week);

- the percentage of patients in the subgroup of IBS with a predominance of constipation, in whom the number of bowel movements increased by an average of 1 time per week compared to the baseline;

- dynamics of clinical symptoms of IBS, visceral sensitivity index, severity of anxiety and depression, changes in quality of life, as well as the need for symptomatic medications (Smecta®, Guttalax®, No-shpa®), which have been approved for use to relieve symptoms of the disease (diarrhea/constipation /abdominal pain).

The most objective tool for assessing the severity of abdominal pain/discomfort and its outcomes during therapy is the data provided by the patient (Patient Reported Outcome), which is expressed in arbitrary units/points using validated scales. One such tool used in this study is the 11-point visual analogue scale (VAS), which ranks pain severity from 0 to 10 (Numeric Rating Scale). To assess the clinical manifestations of IBS and their dynamics during therapy, in addition to the VAS, the following scales and questionnaires were used: VAS assessment of the severity of IBS symptoms (Visual Analog Scale - Irritable Bowel Syndrome - VAS-IBS), Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI), hospital anxiety and depression scale (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - HADS), quality of life questionnaire for IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome - Quality of Life - IBS-QoL).

At the screening stage, a history and complaints were collected, physical, laboratory and instrumental examinations were taken, with the help of which causes of pathological symptoms other than IBS were excluded. Instrumental and laboratory examinations included colonoscopy, biopsy and histomorphological studies if indicated, ultrasound examination of the abdominal and pelvic organs, 12-lead electrocardiography, general clinical blood and urine tests, biochemical analysis of blood serum with determination of C-reactive protein, total protein, creatinine , glucose, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, amylase, stool examination with assessment of physicochemical (consistency, color, smell, reaction, bilirubin, stercobilin) and microscopic indicators (muscle fibers, neutral fat, fatty acids, soaps, fiber, leukocytes, erythrocytes and other indicators), analysis for dysentery group and helminth eggs.

During the 2-week screening observation (visits 1 and 2), patients kept diaries, which made it possible, along with questionnaires and testing, to assess the initial severity of the main symptoms of IBS. After inclusion in the study (visit 3, day 0), patients were randomized into one of two groups. Patients of group 1 (Kolofort group) received the study drug 2 tablets 2 times a day for 12 weeks, patients of group 2 (placebo group) received placebo according to the Kolofort dosage regimen.

During the subsequent treatment period, patients made 5 visits (4–8 visits) to the medical center, during which the condition was assessed, objective and laboratory examinations, testing and questionnaires were carried out, concomitant therapy, possible adverse events, and compliance were recorded. Throughout the study, patients continued to keep a diary, where they recorded their condition, possible pathological symptoms, adverse events, and intake of the study and concomitant medications.

Subgroups with IBS with a predominance of diarrhea (n=48; 42%) or constipation (n=50; 44%) were equal in number; a significantly smaller number of patients had a mixed variant of IBS (n=16; 14%). Concomitant diseases were registered in 55% of study participants, including diseases of the circulatory system (20%, including arterial hypertension, which was detected in 12% of patients), inflammatory and non-inflammatory diseases of the genitourinary system (25%), spine/joints/soft tissues ( 16%), respiratory (15%) and endocrine (8%) systems. Pathology of the nervous system (9%) was recorded mainly in the form of asthenovegetative and neurosis-like disorders, typical for patients with IBS. As a concomitant therapy, 7% of patients received antihypertensive therapy, 14% of female participants of childbearing age used oral combination drugs for contraception. During the study, various drugs were used for the treatment of acute respiratory infections, including antiviral drugs (4%), rarely - drugs from other groups (statins, hypoglycemic drugs, etc.).

During the entire study, patients could receive symptomatic therapy for IBS (Smecta®/Guttalax®/No-shpa® - if indicated) and drugs for the treatment of concomitant pathologies with the exception of prohibited drugs, which included drugs affecting the gastrointestinal tract (laxatives, prokinetics, antispasmodics) , opiate receptor agonists); carminatives, antibiotics, non-steroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, psychotropic drugs (antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, lithium and sedatives), probiotics and other drugs whose instructions for medical use indicate an effect on the functional state of the intestine.

Statistical processing of the obtained data was carried out using the statistical package SAS 9.3. From the elements of descriptive statistics, the following were determined: arithmetic mean, standard deviation, number of observations - for quantitative characteristics; shares and percentages of patients with one or another indicator - for qualitative characteristics. Methods of parametric (for continuous and interval variables) and nonparametric (frequency analysis for categorical variables) statistics were used.

Results and discussion

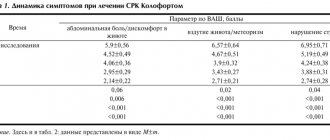

The initial average pain intensity at the screening visit was 6.1±1.7 points in patients in the Kolofort group and slightly lower (5.6±1.5 points) in patients in the placebo group. Despite the use of approved medications to alleviate the symptoms of the disease during 2 weeks of observation, the intensity of abdominal pain by the 3rd visit (day 0) remained virtually unchanged, remaining more pronounced in the Kolofort group (6.0±1.7 points vs. 5.2±1.6 points in the placebo group).

A decrease in pain intensity by 30% or more compared to the initial state was recorded in 56% of patients after 4 weeks and 90% of patients after 12 weeks of treatment with Kolofort, which, according to frequency analysis, was significantly superior (c 2(1) = 8. 7; p=0.003) results in the placebo group (67%). The decrease in pain intensity occurred on average by more than 50%.

In approximately 1/3 (31%) of the study participants, abdominal pain was almost completely relieved by the end of the treatment period (reduction in intensity by 90–100%); in the placebo group there were 2 times fewer such patients (16%). A significant reduction in abdominal pain was recorded in patients who responded to Kolofort therapy for more than 50% of the observation period. In addition, it was noted that during treatment with Kolofort, all participants experienced an improvement in the main symptom of the disease, and in the placebo group, 11% of patients showed a deterioration; the intensity of the pain syndrome increased after 12 weeks (Fig. 1).

Rice. 1. Distribution of patients according to the dynamics of abdominal pain after 12 weeks of treatment.

The severity and dynamics of abdominal pain in patients of the Kolofort group did not depend on the use of No-shpa, which is approved for the relief of spastic abdominal pain. If the initial frequency of its use was 8.0±8.7 times over 2 weeks of observation, then by the end of therapy it was 4 times or more lower (1.8±3.6 times over 2 weeks; ANOVA Repeated Measures: F( 3/333)=3.04; p=0.03).

Thus, treatment with Kolofort eliminated motor and receptive visceral dysfunction of the intestine and hyperalgesia due to the influence on the central and peripheral mechanisms of the formation of abdominal pain, significantly reduced its severity and reduced the need for analgesic (antispastic/spasmolytic) therapy. A pronounced analgesic effect developed gradually and was observed in 100% of patients.

The therapeutic effect of Kolofort was manifested by a positive effect on stool pattern (form and frequency) in patients with different types of IBS.

13% of patients in the Kolofort group with IBS with predominant diarrhea initially had type 7 (watery), 87% had type 6 (mushy) stool with 100% bowel movements. After just 2 weeks of treatment with Kolofort, an improvement in stool consistency/shape to type 5 occurred in 61% of patients. In the placebo group, on the contrary, 60% of participants remained type 6 stools. As a result of a 3-month course of therapy, 96% of patients in the Kolofort group had stool type 5 or lower (versus 72% of the placebo group; c 2(1) = 5.5; p = 0.02); including almost 1/2 of the patients had a normal type of stool (4th - in 35%; 3rd - in 13%); at the same time, the frequency of stools decreased from 3 times or more to 1–2 times per day (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Dynamics of the proportion of patients with stool improvement to type 5 or less according to the Bristol scale

Positive changes in the consistency/shape of stool were associated specifically with the therapeutic effect of Kolofort, and the need of patients to use the approved Smecta decreased by 30% in the first 2 weeks of treatment. The result of 12 weeks of use of Kolofort was a 70% reduction in the need to use the drug to relieve diarrhea (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Proportion of patients taking Smecta®.

A decrease in the intensity of abdominal pain in patients of the IBS subgroup with a predominance of diarrhea by approximately 25% occurred after 2 weeks of treatment with Kolofort and by more than 50% after a month. Starting from the 2nd month, the analgesic effect of the drug increased and reached more than 70%. At the same time, a decrease in the intensity of abdominal pain syndrome by 30% or more was observed in 100% of patients with positive dynamics of stool shape according to the Bristol scale, which significantly exceeded the effect of placebo therapy (c 2 (1) = 7.7; p = 0.006). Thus, in parallel with the restoration of stool patterns in 96% of patients, a decrease in the severity of the pain syndrome occurred in 100% of patients in the IBS subgroup with predominant diarrhea (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. Proportions of patients with a simultaneous decrease in the intensity of abdominal pain and improvement in stool pattern in patients with IBS with diarrhea predominance.

The Kolofort effect in participants in the subgroup of IBS with a predominance of constipation also manifested itself in the first 2 weeks of treatment - the average stool frequency from the initial 1–2 times a week (without the use of laxatives) and 2.9±1.5 times a week (with the use of Guttalax ) increased to 4.3±2.0 times in 7 days. In just 12 weeks of therapy, the frequency of bowel movements increased by 2.5±1.7 times per week, averaging 5.4±2.1 times per 7 days. The proportion of patients who experienced an increase in stool frequency by 1 or more times per week was 69% and did not depend on taking Guttalax. During the first 2 weeks, the frequency of its use decreased by almost 2 times, and after 3 months of treatment with Kolofort - by more than 5 times. By the end of therapy, only a third of the patients required rare (once every 2 weeks) use of Guttalax (Fig. 5).

Rice. 5. Dynamics of stool frequency and Guttalax intake in patients with IBS with a predominance of constipation, treated with Kolofort.

Simultaneously with the improvement in stool pattern in this variant of IBS, i.e., starting from the first weeks of use, the analgesic effect of Kolofort appeared. By influencing the cause and pathogenesis of the formation of pain, the treatment had a pronounced analgesic effect and led to an increase in stool frequency while reducing the need for symptomatic therapy in 84% of patients in the subgroup of IBS with a predominance of constipation (Fig. 6).

Rice. 6. Dynamics of abdominal pain in patients with IBS with a predominance of constipation.

A significant improvement in stool pattern in subgroups of IBS with a predominance of diarrhea/constipation, indicating restoration of motor-evacuatory function of the gastrointestinal tract during treatment with Kolofort, was confirmed by the results of analysis of data obtained using the VAS-IBS scale. The total VAS-IBS score, which allows assessing the effect of the drug on both intestinal symptoms and the psychological state of the patient, significantly decreased from the initial 32.2±9.3 to 14.0±10.7 points (F(2/ 224)=43.4; p<0.0001), significantly exceeding the effect of placebo therapy (F(1/112)=4.3; p=0.04); rice. 7.

Rice. 7. Dynamics of the total score of the VAS-IBS scale during treatment.

It should be noted that the positive dynamics in the form of a decrease in the severity of the main clinical symptoms of IBS progressively increased throughout the entire 12 weeks of using Kolofort and did not reach a plateau by the end of the treatment period, which may indicate the advisability of extending the course of therapy to achieve maximum effect in 100% sick.

The severity score of intestinal symptoms also decreased significantly (F(2/224)=38.68; p<0.0001) and prevailed over the placebo effect (F(1/112)=4.29; p=0.041). Treatment with Kolofort had a significant effect on all intestinal symptoms: discomfort and bloating, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea and constipation (Fig. 8); the percentage of patients who had an imperative urge to defecate and a feeling of incomplete bowel movement decreased.

Rice. 8. Dynamics of intestinal symptoms according to the VAS-IBS scale: a - bloating and flatulence; b - diarrhea; c - vomiting and nausea; g - constipation.

The noted positive changes were associated with the corrective effect of the drug on visceral sensitivity, as evidenced by a significant change in the VSI (Visceral Sensitivity Index) during Kolofort therapy (F(2/224)=7.5; p<0.0001); rice. 9.

Rice. 9. Dynamics of the visceral sensitivity index during treatment.

Thus, treatment with Kolofort had a corrective effect on the manifestations of nociceptive dysfunction, visceral sensitivity and hyperalgesia, which underlie the formation, progression and clinical manifestation of IBS.

The central effects of Kolofort were manifested by anxiolytic (ANOVA: F(2/220)=10.27; p<0.0001) and antidepressant (F(2/220)=7.50; p=0.0007) effects (Fig. 10 ), which plays a very important role in the treatment of patients with IBS.

Rice. 10. Dynamics of the severity of anxiety and depression on the HADS scale during treatment.

At baseline, 1/3 (34%) of patients in the Kolofort group had clinically significant anxiety, 1/4 of the participants had subclinical/clinically significant depression. During therapy, the percentage of patients with no anxiety disorders and depression increased significantly, and the percentage of patients with subclinically/clinically significant anxiety/depression decreased (Fig. 11).

Rice. 11. Proportions of patients in the Kolofort group with varying degrees of anxiety during treatment.

The described positive changes that occurred during treatment with Kolofort, including a significant reduction or complete absence of abdominal pain syndrome, improvement or restoration of numerous intestinal disorders in combination with the correction of psycho-emotional disorders, had a positive impact on the quality of life of study participants. Assessment using the IBS-QoL scale, developed specifically for patients with IBS and allowing to assess the impact of therapy on various aspects of the patient’s physical and mental health, showed a progressively increasing increase in the total score, which ultimately increased by an average of 16.2 (Fig. 12) .

Rice. 12. Changes in quality of life according to the IBS-QoL scale during treatment.

Analysis of variance for repeated measurements confirmed a significant improvement in the quality of life indicator by the end of therapy (factor “visit”: F(2/224)=30.75; p<0.0001).

Sequential analysis of each item of this questionnaire showed positive assessments of patients at the end of therapy, which were a consequence of the fact that the use of Kolofort significantly reduced the negative impact of problems associated with the disease. Most patients noted a marked decrease in the feeling of discomfort, which is understood as unpleasant sensations in the abdomen caused by increased peristalsis, flatulence, bloating, and spastic phenomena. As a result of the fact that life “no longer revolved around problems related to the intestines,” patients became more mobile, active, “managed to do much more due to the reduction/disappearance of intestinal problems,” their tolerance to physical activity increased, patients became less irritable and more stress-resistant. Finally, the patients' social and personal lives, including their sexual lives, improved during treatment.

The effectiveness of therapy was combined with a high level of safety of Kolofort. The absence of adverse events recorded during the study that had a reliable connection with therapy, the results of re-evaluation of patients’ vital functions and their laboratory tests made it possible to confirm the safety of the drug, which was comparable to the safety of placebo. It should be noted the high level of patient adherence to this treatment regimen with Kolofort (close to 100% compliance rate), low (less than planned) rate of patient dropout during the study, including due to ineffectiveness of therapy, the absence of cases of incompatibility of the drug with drugs of different classes, used for the treatment of underlying and concomitant pathologies.

Conclusion

The study showed that Kolofort has a pronounced analgesic effect in patients with all types of IBS, this manifested itself in the form of a decrease in the intensity of the main (primary) symptom of the disease - abdominal pain. In 90% of patients who responded to Kolofort therapy, a significant reduction in the severity of abdominal pain was recorded over 50% of the observation period. In 1/3 of the study participants, the pain syndrome was completely relieved by the end of the treatment period. The analgesic effect developed during the first 2 weeks of therapy and was observed in 100% of patients. No worsening or exacerbation of the disease was recorded during treatment with Kolofort.

A decrease in the severity of abdominal pain syndrome and restoration of motor-evacuation function of the gastrointestinal tract during treatment with Kolofort occurred due to the impact on the central and peripheral links of the pathogenesis of IBS. The therapeutic effects of the drug were due to the influence of its components (anti-TNF-a, anti-S100 and anti-H) on visceral hypersensitivity and hyperalgesia, subclinical inflammation and psychophysiological disorders.

As a result of treatment, the severity of abdominal pain and other gastroenterological symptoms associated with impaired transit of intestinal contents, increased gas formation and other pathological changes in the intestine decreased. Kolofort had a significant positive effect on stool pattern (form and frequency) in patients with different types of IBS. By the end of 3 months of therapy, of 96% of patients in the IBS subgroup with predominant diarrhea who responded to treatment, 1/2 of the patients had a normal type of stool; at the same time, its frequency decreased from 3 times or more to 1–2 times per day; In 100% of patients with positive dynamics of stool shape according to the Bristol scale, there was a significant decrease in the intensity of abdominal pain syndrome.

The average stool frequency in patients of the IBS subgroup with a predominance of constipation increased from the initial 1–2 times a week to 3–7 times in 7 days; simultaneous improvement of stool pattern and the analgesic effect of Kolofort were registered in 84% of patients.

All patients noted a decrease in the severity of “non-gastroenterological” somatovegetative and psychophysiological disorders, an increase in physical and mental performance, activity and stress resistance, a decrease in irritability and emotional lability. The result of the positive impact on various aspects of physical and mental health was the improvement of the patient’s daily, social and personal, including sexual, life, i.e. quality of life in general.

Thus, the results of a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study indicate the effectiveness and safety of Kolofort in the treatment of patients with different types of IBS. The recommended duration of treatment with Colofort should be at least 3 months, and taking into account the increasing effect over the 12-week course, it can be recommended to extend it to 6 months.

Literature

- Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. NEJM 2012; 367:1626–35.

- Engsbro AL, Simren M, Bytzer P. Short-term stability of subtypes in the irritable bowel syndrome: prospective evaluation using the Rome III classification. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35 (3): 350–9.

- Ford AC, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 2012; 345:e5836.

- Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human use (CHMP). 27 June 2013. CPMP/EWP/785/97 Rev.1.

- Braak B, Klooker TK, Wouters MM et al. Mucosal immune cell numbers and visceral sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: is there any relationship? Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 10 (5): 715–26.

- Trentacosti AM, He R, Burke LB et al. Evolution of clinical trials for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Issues in end points and study design. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 730-4.

- Agafonova N.A. Pathogenetic therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Cons. Med. 2012; 14 (8): 47–51.

- Keszthelyi D, Troost FJ, Masclee AA. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology.Methods to assess visceral hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liever Physiol 2012; 303: G141—G154.

- Ludidi S, Conchillo JM, Keszthelyi D et al: Rectal hypersensitivity as hallmark for irritable bowel syndrome: defining the optimal cut off. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 24: 729-33.

- Simren M, Barbara G, Flint HJ et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut 2012; 62: 159-76.

- Kim HS, Lim JH, Park H, Lee SI. Increased Immunoendocrine Cells in Intestinal Mucosa of Postinfectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients 3 Years after Acute Shigella Infection — An Observation in a Small Case Control Study. Yonsei Med J 2010; 51(1):45–51.

- Kim SE, Chang L. Overlap between functional GI disorders and other functional syndromes: what are the underlying mechanisms? Neurogastroetnerol Motil 2012; 24: 895-913.

- Guidance for Industry. Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Clinical Evaluation of Products for Treatment. US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). May 2012. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM20526..

- American College of Gastroenterology IBS Task Force: An evidence based position statement on the management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: S1–S35.

- Zueva E.P., Krylova S.G., Guryanova N.N. and others. Experimental study of the effect of the drug Kolofort on the motor-evacuation function of the gastrointestinal tract of mice. Abstracts of reports of the XIX Russian National Congress “Man and Medicine”. M., 2012.

- Epshtein O.I. Ultra-low doses (history of one study). M.: Publishing house of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, 2008.

- Ertuzun I.A., Zueva E.P. and others. Experimental study of "Kolofort" - a new drug for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and other functional diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Bulletin of VolSMU. 2012; 4 (44): 25-7.

- Voronina TA, Sergeeva SA, Martyushev-Poklad AV et al. Antibodies to S-100 Protein in Anxiety-Depressive Disorders in Experimental and Clinical Conditions. "Animal Models in Biological Psychiatry". Ed. Kalueff AV New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2006; 8: 137-52.

- Ohman L, Simron M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7 (3): 163–73.

- Zueva E.P., Krylova S.G., Guryanova N.N. and others. Experimental study of the antispasmodic activity of the drug Kolofort in mice. Abstracts of reports of the XIX Russian National Congress “Man and Medicine”. M., 2012.

Intestines, digestion, nerves

Alina

July 12, 2020

Dear doctors, good afternoon!! I write here more than once!!! I’m worried about my stomach and intestines! You advised me here on medications, etc.! At the moment I took Alpha Normix for 10 days and enterol, switched to the bifinic synbiotic 1 piece at night!!! I also drink Mezim 10 thousand units 1 piece 3 times a day and Omez D 2 times a day and Trimedat 3 times a day!!! I was worried about nausea and aversion to food, at the moment it has practically gone away! I have breakfast more or less like Okhotskaya, I have lunch and dinner too!!! but I continue to be bothered by pain in the stomach and abdomen!!! Dedudou periodically has cramping pain, not constantly! But the intestines , stomach, as if in tension all the time!!! sometimes from the right it pulls, then to the left, then lower, then higher!!! at night it sometimes rumbles and gurgles! 2 days ago the right side really pulled at night, the next night the left side!!! During the day there is periodic discomfort! The lower back also hurts, but I had SHOH, maybe the lower back hurts from it! Mostly the pain is in the lower back, sometimes also in the shoulder blades!!! pain from the lower back can radiate to the stomach and can’t be overcome from the stomach to the lower back, I don’t understand!!! periodically right in the middle between the ribs at the bottom it hurts and it pulls and stings!!! before that, when I had problems with nausea, I ate very little and very poorly in 1.5 months, I lost 4.5 kg!!! now I eat normally, I’m trying!!! but weight is not gained yet! stool every day from 1-3 times! without blood, and mucus, shaped, light brown, like mustard!!! Today I went to the toilet normally at first, and an hour later I went again and the stool was ribbon-shaped! (But I pushed because at first there was Gas and I also have internal hemorrhoids that come out during defecation!!! I attach all the tests that are available! Software Ultrasound is all fine, the only thing is the splenic vein is enlarged up to 7 mm or something, but I’m thin, my veins are clearly visible everywhere! According to FGDS, DUODENITIS AND ERYTHEMATOUS GASTROPATHY! I took the first capprogram after menstruation and did not collect it correctly and the food was all in a row, there was mucus and hidden blood and red blood cells with leukocytes, retested and everything is fine! Help me figure out what to do next, how long it will take for all this to recover, I understand that the process of developing the gastrointestinal tract is a long one! And especially in my case, it all started against the backdrop of nerves and stress! but so somehow there is pain, discomfort, or pulling in the lower back, and now ribbon-shaped feces have appeared! I’m starting to panic!!! (all the times before this the stool was normal!!!

Age:

28

The question is closed

small of the back

this moment

periodic spinning