Irritable bowel syndrome (hereinafter referred to as IBS) is a functional intestinal disorder in which abdominal pain is combined with disturbances in bowel movements and intestinal transit.

Normal stool – in healthy adults who adhere to a mixed diet, the frequency of stool is from 3 times a day to 3 times a week, the weight of stool is 100–250 g/day, the stool has a formed consistency.

Irritable bowel syndrome according to ICD-10 is classified as:

- K58.0 irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea;

- K58.9 irritable bowel syndrome without diarrhea.

Clinical criteria for IBS are:

- pain and (or) discomfort in the abdominal area; reduction of pain and discomfort after defecation; no night pain;

- diarrhea without blood, mainly in the morning after breakfast, sometimes mixed with mucus and undigested food residues; imperative urge to defecate; no diarrhea at night;

- constipation (stool less than 3 times a week, dense), the need for intense straining during bowel movements, a feeling of incomplete bowel movement; fragmented stool with mucus discharge;

- alternating diarrhea and constipation;

- bloating;

- absence of “alarm symptoms”: diarrhea at night, blood in the stool, weight loss, fever, anemia, laboratory signs of inflammation.

Causes of IBS with constipation

When self-treating irritable bowel syndrome, you should know the factors that lead to it.

- Psychological - emotional tension, stress. IBS in this regard is a vicious circle. Irritation that does not find a rational explanation and solution leads to the syndrome. The disease reduces the quality of life, provoking negative emotions.

- Social - unfavorable conditions, for example, poor nutrition.

- Biological - intestinal infections.

Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation is recognized by most researchers as a psychosomatic disease. Indeed, past infections can aggravate the condition, but the main cause of the disease lies in other mechanisms. What distinguishes IBS from other types of disorders is that it does not occur due to structural changes in the intestinal walls.

The mechanism of its development is a violation of the nervous regulation of intestinal motor function. Thus, Sheptulin notes in his work that “IBS is in many cases a unique clinical form of neurosis, in which intestinal disorders become the leading clinical symptoms” (Sheptulin A. A., 1999, p. 8).

People with IBS have a higher sensitivity of the intestinal apparatus to stretching, since the threshold for receptor excitability is lower. This leads to pain and discomfort. In this case, constipation can be associated with both a weakening and an increase in propulsive intestinal motility. Propulsive peristalsis ensures the movement of intestinal contents to the anus.

The leading causes of the syndrome are psychosocial factors. We can talk about both chronic stress and high workloads, social unsettlement, one-time peak loads and shocks. Scientists talk about a certain genetic predisposition to the disease.

The condition for the appearance of visceral hypersensitivity can be certain factors: +

- past infections;

- stress, trauma,

- operation, etc.

These factors change intestinal motility. As a result, a stimulus of normal intensity (for example, a small volume of gases moving through the intestine) leads to an increased pain response.

Treatment of a patient with IBS

- psychotherapy (any option except relaxation psychotherapy);

- measures to correct nutrition and lifestyle: quitting smoking, normalizing the diet, training in intestinal hygiene and establishing a bowel movement (for constipation), using a diet limiting fermentable di- and oligosaccharides for persistent flatulence, caution in the use of NSAIDs and other drugs, having intestinal symptoms or colitis as side effects;

- drug therapy for intestinal manifestations, which is determined by the dominant symptom: for pain - drugs used for intestinal dysfunction for 4-8 weeks, if necessary, longer use is possible: otilonium bromide 40 mg 3 times a day; mebeverine hydrochloride 200 mg x 2 times/day; trimebutine 100 mg 3 times a day; hyoscine butylbromide 10 mg 3 times a day;

- for constipation - laxatives, doses, regimen and duration of administration of which are selected individually, taking into account the severity of symptoms and response to treatment: bisacodyl 1-2 tablets (5-10 mg) at night or 1-2 suppositories rectally; lactulose 15–45 ml/day, followed by a transition to a maintenance dose of 10–25 ml/day; macrogol 4000 1–2 packets (10–20 g) per day;

- for diarrhea - loperamide 2 mg in the form of single doses “on demand”;

- for flatulence - drugs based on simethicone 40-80 mg 2-3 times a day in the “on demand” mode;

- if the effect of the above therapy is insufficient, tricyclic antidepressants are used in small doses to reduce intestinal manifestations: amitriptyline 10–50 mg/day for 8–12 weeks; if there is no effect from the above therapy, probiotics in medium therapeutic doses for 4 weeks.

Monitoring the effectiveness of patient treatment is carried out clinically to relieve complaints.

Patients with IBS belong to the follow-up group D(II).

Symptoms

In irritable bowel syndrome with a predominance of constipation, the clinical picture from the gastrointestinal tract includes the following signs:

- bowel movements less than three times a week;

- hard consistency;

- straining;

- feeling of incomplete bowel movement;

- abdominal pain, bloating.

The feces may not just be hard, but bean-shaped. Other symptoms of IBS with constipation include a false urge to have a bowel movement, the release of mucus during bowel movements, and a feeling of transfusion.

Constipation develops against the background of pain, which is of particular importance in diagnosis - this is how IBS can be distinguished from functional constipation, it is not accompanied by such severe pain.

Pain can vary: from dull pain to acute spasms, from constant pain to paroxysmal pain. Painful sensations may last several minutes or hours.

People with IBS often report other symptoms: frequent urination; in women, painful periods, increased fatigue, headaches, and aching back pain. Changes also affect the psycho-emotional sphere of a person: suspiciousness, anxiety, and irritability may occur.

The author N. S. Zhikhareva in her scientific work emphasizes that “IBS is a diagnosis of exclusion.” This means that symptoms may be similar to those of other disorders, and testing is required to make a diagnosis.

Diagnosis and treatment

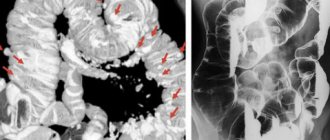

The diagnosis of IBS is established on the basis of complaints, anamnestic data and diagnostic examination. Diagnostics include a general blood and urine test, a biochemical blood test, a coprogram, a survey radiography of the abdominal organs with contrast using barium sulfate, irrigoscopy and colonoscopy. As a rule, these diagnostic manipulations are sufficient to confirm the diagnosis. If indicated, this spectrum can be expanded (ultrasound, CT, MRI and much more). Treatment of the disease is carried out conservatively, through the prescription of medications. Drug therapy consists of:

- Antispasmodic drugs: drotaverine, dicytel.

- Anxiolytics: atarax.

- Probiotics necessary to normalize the intestinal microbiota.

- Antidiarrheals: loperamide.

- Antibiotics: rifaximin, metronidazole.

The prescription list and dosage of prescribed medications is compiled individually for each patient and depends on a number of factors: gender, age, history of concomitant diseases, severity of the condition, and much more. In addition, a mandatory component of successful recovery is diet and normalization of diet. To do this, it is necessary to exclude carbonated drinks, fatty foods, alcoholic drinks, and reduce the daily consumption of fresh vegetables and fruits.

Often, irritable bowel syndrome is activated after suffering stress or severe psycho-emotional stress. Therefore, patients are strongly advised to avoid stressful situations, and if indicated, consult a psychotherapist for professional help.

Danger and complications

IBS with a predominance of constipation reduces a person’s quality of life. A prolonged absence of stool can cause chronic intoxication of the body, depletion of defenses, exacerbation of dermatological diseases and allergies. Pain contributes to a reduced emotional background, can limit social activity, and cause irritability and nervousness.

In the long term, persistent constipation can be a risk factor for the development of cancer of the digestive system, atherosclerosis, thrombosis, heart attacks, and strokes. Stagnation of feces leads to overstretching of the intestinal walls and accompanying structural changes and inflammatory processes.

Treatment

Drug treatment for IBS should be prescribed by a doctor. Non-drug methods include:

- diet,

- psychotherapy.

The use of medications is determined by the form of the syndrome. If constipation predominates, the following groups of medications can be used:

- modern antispasmodics that do not affect the functioning of the cardiovascular system;

- bulk laxatives;

- gastroprokinetics, which stimulate intestinal motility.

Among bulk laxatives, psyllium is of particular importance. Herbal preparations have been developed on its basis. Psyllium is obtained from plantain seeds. Psyllium retains water in the intestines, increases the volume of intestinal contents and softens stool, resulting in a mild laxative effect. As a rule, such products are approved for long-term use.

Symptomatic treatment of IBS with constipation may include the use of osmotic laxatives as indicated, but it is better to avoid taking them regularly. As a rule, such funds are used in preparation for endoscopic diagnosis. They cause the so-called drastic effect, frequent and profuse, watery stools, and can also increase pain.

A separate method of treatment is the prescription of anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants. But such means should be used with caution. Doctors usually prescribe them in short courses lasting up to 14 days, mainly during periods of severe stress. For example, this may be appropriate for a patient going through divorce proceedings or a student who is about to start a session.

Long-term use of anxiolytics, or anti-anxiety drugs, leads to a decrease in their effectiveness and the development of addiction. Antidepressants are also prescribed strictly according to indications, but the paradox is that they can cause constipation - many drugs in this group have such a side effect. Therefore, it is better to weigh everything and discuss this approach in detail with your doctor. In some cases, it is advisable to get by with a course of psychotherapy.

The development of a diet should be based on the individual characteristics of a person’s health status and the leading symptoms of the syndrome. If additional fiber may be contraindicated in IBS with diarrhea, then constipation is a reason to reconsider the diet. Products with coarse fiber will help cope with the symptom.

The incidence of lactase deficiency in people with IBS is the same as in healthy individuals. But eliminating dairy products from your diet can be helpful. Sheptulin explained this in detail: “It should be borne in mind that in a number of patients with IBS, diarrhea may be a manifestation of individual intolerance to any food products. In such cases, elimination diets can have a good effect” (Sheptulin A. A., 1999, p. 8).

Diet therapy for IBS with constipation

Diet for IBS with a predominance of constipation does not imply the complete exclusion of any foods. Their number may be reduced due to the fact that they cause dyspeptic disorders. An increase in the volume of plant fibers is shown. This concept includes two types of fibers with different effects:

- soluble - increase the volume of feces and soften them, stimulate peristalsis;

- insoluble - also affect intestinal motor function, but with an emphasis on thorough removal of toxins, creating a favorable environment for the renewal of microflora.

The basis of the diet should be the following products:-

- lean meat, poultry;

- low-fat fish;

- cereals, crumbly porridges in water;

- vegetable oils;

- dairy products;

- fruits, vegetables, berries;

- dried fruits;

- bran bread

It is necessary to steam or boil dishes, and eat first courses daily. You can eat steamed omelettes, mousses, and choose buckwheat, pearl barley and other cereals as a side dish. It is better to avoid foods with an astringent, fixing effect, as well as foods that increase gas formation.

Restrictions apply to cabbage, legumes, fresh white bread, chocolate, cottage cheese, yesterday's kefir, tea and coffee, quince, pomegranate, rice, crackers, hard-boiled eggs.

It is important to review your diet if you have irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, but introduce additional dietary fiber gradually to prevent a deterioration in your well-being and increased pain. Some patients note that including bran in their diet increases bloating and pain.

Doctor Sheptulin tells what to do in this case: “Taking psyllium can have a good effect: it retains water, thereby increasing the volume of intestinal contents, and does not cause an increase in gas formation” (Sheptulin A. A., 2001, p. 538).

The English drug “Fitomucil Norm” will quickly increase the amount of fiber in your diet. Intestinal constipation is relieved gently and predictably. The biocomplex contains the shell of plantain psyllium seeds and dry fruits of domestic plum. Does not cause pain or spasms.

Find detailed information about the composition on the website.

Irritable bowel syndrome in children: main causes and approaches to treatment

Personal and psychological aspects, genetic predisposition, nutritional factors, changes in visceral hypersensitivity, disorders of motor activity and the neuroendocrine system (brain-gut axis), increased intestinal permeability, and disruption of the composition of the intestinal microbiota are important in the development of the disease. Qualitative and quantitative changes in microflora affect intestinal function, acting as a cause of disturbances in its motor activity, sensitivity and neuroimmune relationships, including impaired expression of mucosal receptors and changes in the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system. In pediatric practice, the possibilities of using medications are significantly limited by the age of the patients. In therapy, preference should be given to selective drugs that affect visceral sensitivity and probiotics with proven effectiveness and safety of strains.

Information about authors:

Zakharova Irina Nikolaevna – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Pediatrics named after. G.N. Speransky Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Further Professional Education "Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education" of the Ministry of Health of Russia;; e-mail: [email protected]

Sugyan Narine Grigorievna – Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Pediatrics named after. G.N. Speransky Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Further Professional Education "Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education" of the Ministry of Health of Russia;

Berezhnaya Irina Vladimirovna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Pediatrics named after. G.N. Speransky Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Further Professional Education "Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education" of the Ministry of Health of Russia.

Key words : children, irritable bowel syndrome, prokinetics, trimebutine, neobutin, probiotics, maxilac.

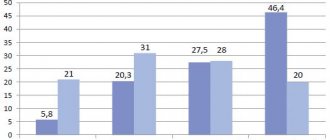

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional bowel disease in adults, representing a significant social problem with a negative impact on quality of life. In most countries of the world, the incidence of IBS averages about 20%, ranging from 9 to 48%. There is little information on the prevalence of IBS in children; for example, in the USA, according to various authors, the frequency ranges from 1.2 to 2.9% [1]. It is difficult to estimate the prevalence of IBS in the population, since statistical data vary significantly even in different regions of the same country. Epidemiological indicators, summarized from questionnaires in different countries of the world, show that the numbers range from 10 to 25%. According to the meta-analysis, the overall prevalence of the disease was about 11.2% (95% CI, 9.8–12.8) with differences in regions of the globe: from the lowest in South Asia (7%) to the highest in South Asia. America (21%). It has been shown that in the first few months after the diagnosis of IBS, patients suffer up to 4 attacks with severe abdominal pain. Subsequently, in 30–40%, the light intervals between exacerbations increase. Approximately half of patients with IBS (45%) develop chronic diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract (dyspepsia, chronic gastritis, GERD, etc.) after several years of IBS.

Functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract are one of the most mysterious problems of modern medicine, since, despite the huge range of diagnostic procedures, it is not possible to fully understand the etiology and pathogenesis. We have been using clinical guidelines known as the Rome criteria for about 30 years. In 2021, a new edition of the clinical guidelines for functional gastrointestinal disorders - Rome IV was published, which includes sections of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) in adults, children and adolescents. The emerging evidence base over the past 10 years has provided the basis for the Rome IV Revision recommendations. For some digestive disorders, the committee used clinical experience and consensus of committee members, still lacking reliable scientific evidence, for these sections. In the scientific literature one can find different interpretations of the translation “functional gastrointestinal disorders” - functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), functional disorders of the digestive organs (FDOP) and others. FROP more fully reflects the problem, since the consensus covers functional disorders of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract and biliary tract disorders.

The Rome III criteria emphasized that organic disease must be excluded to establish functional impairment. In the Rome IV Revision Criteria, the phrase “no evidence of an inflammatory, anatomical, metabolic, or neoplastic process explaining the subject's symptoms” was removed from the diagnostic criteria [2]. Instead, it added “after appropriate medical examination, the symptoms cannot be attributed to another disease.” This change allows for random testing to confirm a positive diagnosis of FROP. It has also been noted that FROP can coexist with other organic and chronic inflammatory diseases [3]. In the same way, one patient may have different FROPs. The latest version of the international consensus recommendations Rome IV, published in 2021, considers functional intestinal disorders as a spectrum of intestinal symptoms in 6 categories, which are defined as disorders of the gut-brain interface (GI-CNS). (central nervous system”) (disorders of gut-brain interaction) [4].

The new edition of the Rome IV criteria (2016) includes new disorders: functional nausea and functional vomiting. The wording “abdominal pain associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders” was changed to “functional abdominal pain disorders”. This group includes a new term, functional abdominal pain (aka “FAP-NOS”), to describe children with abdominal pain whose diagnostic criteria are insufficient for inclusion in a specific disorder, such as IBS, functional dyspepsia, or abdominal migraine.

The term “discomfort” in the new version of the Rome IV criteria has been removed from the definition, since it is difficult to distinguish between discomfort and abdominal pain in children. In addition, as a diagnostic criterion, there are no complaints such as bloating, stretching or other sensations of the patient [5].

FROP is based on combined physiological and morphological abnormalities associated with visceral hypersensitivity, disorders of gastrointestinal motility, protective mucosal barrier, immune function and composition of the intestinal microbiota, as well as disorders of the central nervous system.

In the development of FROP in children at an early age, factors such as morphofunctional immaturity, insufficient activity of pancreatic and gastrointestinal enzymes, impaired microbiocenosis, and insufficiency of mucosal immunity play an important role. At an older age, visceral hypersensitivity is caused by a combination of factors: social relationships, stress, overwork, disruption of the daily routine, and rest.

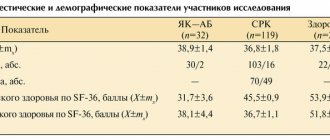

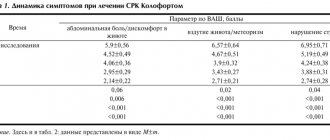

The development of IBS is based on the interaction of two main pathogenetic mechanisms: psychosocial effects and impaired motor function of the colon, which is manifested by an increase in visceral sensitivity and impaired motor function of the intestine (Table 1).

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for IBS for children (signs must be present for at least 2 months) [ 1 ].

| The following symptoms must be present: | |

| 1. Abdominal pain at least 4 days per month associated with 1 or more of the following symptoms: | A. associated with defecation; b. associated with changes in frequency of bowel movements; c. associated with a change in the shape (appearance) of the stool. |

| 2. With IBS with constipation, the pain does not go away after a bowel movement (if the pain goes away after a bowel movement, then the child has functional constipation, not IBS). | |

| 3. After appropriate evaluation, symptoms cannot be attributed to another disease. | |

The pain can be of varying intensity and is usually localized in the lower abdomen, although it can also be noted in other parts of the abdomen. It often intensifies with errors in diet, psycho-emotional stress, worries, and also with physical activity. It is important to note that abdominal pain disappears at night when the child is sleeping.

If the pain goes away after a bowel movement, then most likely the child has functional constipation, rather than IBS with constipation. It has been found that 75% of children suffering from constipation have abdominal pain, which falls under the criteria for IBS. But patients with IBS are observed for a long time with a diagnosis of functional constipation without receiving effective medical care. The committee recommends that patients with constipation and abdominal pain be treated initially only for constipation. If abdominal pain goes away after treating constipation, then the patient has functional constipation. If the pain persists, your child may have IBS with constipation. Likewise for possible IBS with diarrhea. At the first stage, it is necessary to exclude intestinal infection with a recurrent, chronic course, celiac disease, carbohydrate malabsorption and, less commonly, inflammatory bowel disease. It is important to pay attention to alarming signals (“alarm symptoms”, “red flags”), in the presence of which it is necessary to exclude organic pathology of the gastrointestinal tract. It is indicated that the more alarming symptoms are present, the higher the likelihood of organic disease (Table 2). Fecal calprotectin is increasingly used as a non-invasive screening test to rule out inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [6].

Table 2. Symptoms of anxiety in patients with FROP.

| family history of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or peptic ulcer disease; |

| Constant pain in the right upper or right lower quadrant; |

| Dysphagia, odynophagia; |

| Recurrent vomiting; |

| Bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract; |

| Nocturnal diarrhea; |

| Arthritis; |

| Perirectal lesions; |

| Unmotivated weight loss, weight loss, malnutrition; |

| Delayed puberty; |

| Unexplained fever; |

In children, as in adults, IBS can be divided into different types reflecting the predominant stool pattern (IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, IBS with constipation and diarrhea, and unspecified IBS) and these types are now included in Rome IV [7].

Table 3. Functional disorders of the digestive organs: disruption of the interaction of the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system according to the Rome IV criteria (Rome IV and ICD-10 codes).

| C. Intestinal disorders | ||

| C.1 Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | IBS with constipation predominance (IBS-3) IBS with diarrhea predominance (IBS-D) IBS mixed type (SRK-Sm) Unclassified IBS (IBS-U) | |

| Formulation | Rome IV codes | ICD-10 |

| Functional constipation | C.2 | K59.0 constipation K58.2 Irritable bowel syndrome with predominant constipation |

| Functional diarrhea | C.3 | K59.1 Functional diarrhea K58.1 Irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea |

| Functional abdominal bloating/distension | C.4 | R14 Flatulence and related conditions K59.9 Functional bowel disorder, unspecified K58.8 Other or unspecified irritable bowel syndrome |

| Nonspecific functional intestinal disorder | C.5 | K59.2 Neurogenic excitability of the intestine, not classified elsewhere K58.3 Irritable bowel syndrome with mixed manifestations |

| Opioid-induced constipation | C.6 | K59.0 Constipation |

The complexity of the etiopathogenesis of the disease in children is explained by a combination of factors: personal psychological aspects, genetic predisposition, nutritional factors, the development of visceral hypersensitivity, impaired motor activity, changes in the neuroendocrine system (brain-gut axis), increased intestinal permeability, disruption of intestinal composition microbiota.

Scientific studies have shown that visceral hypersensitivity may be associated with childhood psychological stress (anxiety, depression, impulsivity, anger) [8].

Children with IBS may experience increased levels of self-reported stress, anxiety, depression, and emotional problems [9]. Severe illnesses requiring medically invasive intervention at an early age (eg, surgery) are associated with a higher risk of developing PDOP in children, including IBS [10].

The pathophysiology of IBS includes the influence of external irritating factors (stress, high emotional stress, lack of sleep, etc.), which excites the central nervous system, the autonomic response, with an impact on the intestinal neuroendocrine system, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (cortisol) system. This disrupts the motor activity of the intestines, increases spasm of smooth muscles, and disrupts the passage of intestinal contents. On the other hand, changes in intestinal motor activity lead to overexcitation of intraintestinal nerve fibers, Cajal cells, increasing spasm of smooth muscles, the microbiota changes, which affects the environment and the synthesis of SCFA. Thus, a vicious circle arises (Table 4).

Table 4. Pathophysiology of IBS development: the brain-gut connection [11].

| Dysfunction of the brain-gut axis | ||

| Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) | Activation of the enteric nervous system | Change in microbiota |

| Activates CRF-1 receptors → increased motor activity under stress Pro-inflammatory activity → increased synthesis of IL-1 and IL-2 Enhanced response to endotoxins Increased cortisol and adrenaline levels Increased sensitivity of the enteric nerves | Excessive release Neurotransmitters → impaired peristalsis Increased mast cell degranulation → disruption of the serotonin signaling cascade Imbalance in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory and inflammatory mediators Increased intestinal barrier permeability | Violation of local immunity Expression of the synthesis of neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA, histamine, acetylcholine, melatonin, etc.) Disruption of the mucosal barrier and microbial biofilm Modulation of intestinal sensitivity of afferent fibers |

IBS often develops after an acute intestinal infection; an increase in the content of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gastrointestinal mucosa is noted, and post-infectious IBS develops [12]. A systematic review published in 2015 showed the incidence of post-infectious functional dyspepsia and IBS in the population, including children 10.0% (FD, n = 976; OGE, n = 9737) and 13.1% (IBS, n = 1128; OGE, n = 8624), respectively. The long-term persistence of disorders was also indicated; it was found that 1 year after the experience. gastroenteritis, post-infectious functional dyspepsia persisted in 13.5% of patients (n = 380; OGE n = 2807) and irritable bowel syndrome in 38.9% of children (n = 86; OGE n = 221) [13].

Another study indicated the role of parasitic infection (Balantidiumcoli, Strongyloidesstercoralis, Ascarislumbricoides, Necatoramericanus, Ancylostomaduodenale, Taeniasolium, Taeniasaginata and Hymenolepisnana) in the development of post-infectious FROP, in particular in the development of IBS (OR: 1.69), functional constipation (OR: 4.13 ) [14].

The role of intestinal microbiota in the pathophysiology of IBS is currently the subject of a large number of experimental and clinical studies. Changes in the gut microbiome have been demonstrated, although it is unclear whether these changes are a cause or a result of IBS and its symptoms [15].

It has been established that qualitative and quantitative changes in microflora affect intestinal function, acting as a cause of disturbances in its motor activity, sensitivity and neuroimmune relationships, including impaired expression of mucosal receptors and changes in the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system. It is known that intestinal microflora utilizes insoluble carbohydrates and releases metabolites, among which short-chain fatty acids (acetic, propionic and butyric acids) are important. It is these short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in different parts of the colon that have the opposite effect on its motor activity, through stimulation of certain receptors that produce biologically active substances. In the proximal parts of the colon, SCFAs stimulate L-cell receptors, which produce the regulatory polypeptide PYY, which slows down the motor activity of not only the colon, but also the small intestine. And in the distal sections, SCFAs stimulate the receptors of Ecl-cells that produce histamine, which, acting on the 5-HT 4 receptors of the afferent fibers of the vagus nerve, initiates a reflex acceleration of motor activity. Among SCFAs, butyrate (butyrate) is important for colonocytes, which is the most important energy source for colonocytes, membrane lipid synthesis, protective barrier and permeability of the colon mucosa, suppression of oxidative stress, inflammation, colorectal carcinogenesis, restoration of water and electrolyte balance. In addition, butyric acid (butyrate) has a regulatory effect on intestinal motility [16]. SAVanhoutvin et al. studied the effect of butyrate (butyrate) on visceral hypersensitivity in healthy volunteers. Study participants were given butyric acid rectally. The results of the study showed that butyric acid administration increased the pain threshold and reduced the pain and discomfort caused by rectal balloon inflation, as assessed by an analogue scale. It was noted that the administration of butyrate had a dose-dependent effect; the higher the dose of butyrate, the more visceral sensitivity decreased [17].

The use of one of the strains of Bifidobacterium bifidum in patients with symptoms of IBS led to a significant reduction in symptoms such as abdominal pain/discomfort, flatulence, and indigestion in 57% of patients compared to 21% in the placebo group [19].

The meta-analysis assessed the results of 24 clinical trials involving 2001 patients with IBS. The results of the analysis showed a significant reduction in pain and general symptoms in patients using multi-strain probiotics. Multistrain probiotics were evaluated in 12 RCTs involving 1197 patients with a significant effect on abdominal pain symptom (RR = 0.81; 95% CI 0.67–0.98, p

According to studies conducted in patients with IBS, using various probiotics and their combinations, it was found that:

- L. rhamnosus LGG., L. Rhamnosus, B. animalis B. lactis – help stabilize the intestinal microflora [20, 21].

- S.thermophillus, L. acidophilus, B. longum – lead to optimization of the intestinal mucosal barrier [21];

- L. rhamnosus LGG., L. Rhamnosus, B. animalis, B. lactis; L. acidophilus, B. Bifidum – help reduce abdominal symptoms [22];

- B. longum, L. Acidophilus, L. lactis, S. thermophilus, L. plantarum – increase the quality of life of patients [23, 24];

- L. Acidophilus, L. lactis, S.thermophillus (Drouault-Holowacz S et al. A double blind randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination in 100 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008), B. bifidum [25, 26 ] – help eliminate bloating [25].

The results of a systematic review (Simrén M. 2014) confirm the role of synbiotic complexes, a combination of multi-strain probiotics and prebiotics in the complex treatment of IBS manifestations (54).

One of the multi-strain probiotics is Maxilac , which includes bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacteriumbreve, Bifidobacteriumbifidum) and lactobacilli (Lactobacillusacidophilus, Lactobacillusrhamnosus, Lactobacilluscasei, Lactobacillusplantarum, Lactobacilluslactis), Streptococcusthermophilus 108 CFU, as well as the prebiotic component fructooligosaccharide. The innovative DRcaps™ capsule, in turn, neutralizes the negative effects of acidic stomach contents, bile salts and digestive enzymes.

The leading role in the structure of abdominal pain syndrome most often plays spastic visceral pain, which is based on involuntary contraction of intestinal smooth muscles, not accompanied by their immediate relaxation. Selective myotropic antispasmodics have age restrictions in children. In terms of clinical effectiveness, trimebutine is comparable to antispasmodics such as pinaveria bromide and mebeverine in the treatment of abdominal pain in IBS in adults [27].

The mechanism of action of trimebutine is to stimulate peripheral opioid (enkephalin) receptors (μ-, k-, δ-) throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Binding to k-receptors leads to a decrease in muscle activity, and binding to μ- and δ-receptors causes its stimulation. However, the drug does not affect other receptors. Trimebutine has a direct effect on smooth muscle cells through receptors of myocytes and ganglia of the enteric nervous system, imitating the action of enkephalins [28]. There is a generic version of trimebutine on the Russian pharmaceutical market: Neobutin® (available in tablet form in dosages of 100 and 200 mg), which is approved for children from 3 years of age. The drug has a normalizing effect on the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract: depending on the initial state of the gastrointestinal tract, it has a stimulating or relaxing effect on the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, trimebutine, influencing Na+ and Ca2+ channels, provides an anesthetic effect and a direct antispasmodic effect, thus indirectly normalizing gastrointestinal motility and visceral hypersensitivity.

A comparative assessment of the effectiveness of therapy with drugs that coordinate intestinal motility (trimebutine) both monotherapy and in combination with probiotics in children aged 5-17 years with symptoms of IBS was carried out. In the first group (n=15), treatment with trimebutine was carried out at an age-specific dosage for a course of 1 month; in the second group (n=15), combination therapy with trimebutine + probiotics was carried out. The authors determined the level of fecal calprotectin (a protein that reflects the severity of the inflammatory process) as an indicator of inflammation in the intestines. The level of calprotectin in patients with IBS was initially increased in 27.3% of children, the average level of the indicator was 2 times higher than normal values.

The results obtained showed the high effectiveness of trimebutine (in 82% of children) in monotherapy, and the best result (up to 98%) when combining trimebutine with a probiotic. In the placebo group, relief of abdominal pain was observed in 22% of children. Normalization of stool in 99% of children in the second group and 15% in the placebo group [29].

Another study assessed the prevalence of IBS in children and the effectiveness of trimebutine in correcting clinical symptoms. 345 children and adolescents aged 4-18 years were included. The prevalence of IBS according to Rome III criteria in children and adolescents was 22.6%, with IBS with constipation being the predominant subtype. 78 children and adolescents with normal laboratory parameters and an established diagnosis of IBS were randomized into two groups: 39 patients received trimebutine 300 mg per day for three weeks, 39 patients did not receive drug treatment. Clinical improvement was observed in 94.9% of patients treated with trimebutine versus 20.5% in the no-drug group (P

Thus, the use of synbiotic complexes containing a multi-strain composition of probiotic strains of lacto- and bifidobacteria, which have a positive effect on the qualitative and quantitative composition of the gastrointestinal microflora, and trimebutine maleate, which can have a direct normalizing effect on the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract, has grounds for inclusion in complex therapy of irritable bowel syndrome in children.

To learn more

Bibliography

- Van Tilburg MAL, Walker L, Palsson O, et al. Prevalence of child/adolescent functional gastrointestinal disorders in a national US community sample. Gastroenterology 2014;144(Suppl 1):S143–S144.

- Dhroove G, Chogle A, Saps M. A million-dollar work-up for abdominal pain: is it worth it? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;51:579–583.

- Faure C, Giguere L. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and visceral hypersensitivity in children and adolescents suffering from Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1569–1574.

- Drossman DA, Hasler WL Rome IV — Functional GI disorders: disorders of Gut-Brain interaction // Gastroenterology. 2021. Vol. 150 (6). P.1262–1279.

- Jeffrey S. Hyams, Carlo Di Lorenzo, Miguel Saps, Robert J. Shulman, Annamaria Staiano, Miranda van Tilburg. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/ Adolescent // Gastroenterology 2016;150:1456–1468.

- Henderson P, Casey A, Lawrence SJ, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:941–949.

- Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM. Subtypes and symptomatology of irritable bowel syndrome in children and adolescents: a school-based survey using Rome III criteria. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;18:298–304.

- Iovino P, Tremolaterra F, Boccia G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in childhood: visceral hypersensitivity and psychosocial aspects. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21. 940-e74.

- Waters AM, Schilpzand E, Bell C, et al. Functional gastrointestinal symptoms in children with anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:151–163.

- Bonilla S, Saps M. Early life events predispose the onset of childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2013;78:82–91.

- Zakharova I.N., Berezhnaya I.V., Kholodova I.N., Zaidenvarg G.E. Abdominal pain in a child: pediatrician tactics. Training manual for doctors. – M.: FGBOU DPO RMANPO. –2020. – 128 p.

- Saps M, Pensabene L, Turco R, et al. Rotavirus gastroenteritis: precursor of functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:580–583.

- S. Futagami 1, T Itoh, C Sakamoto. Systematic review with meta-analysis: post-infectious functional dyspepsia // Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jan;41(2):177-88. doi: 10.1111/apt.13006.

- Blitz J, Riddle MS and Porter CK (2018) The Risk of Chronic Gastrointestinal Disorders Following in Acute Infection with Intestinal Parasites. Front. Microbiol. 9:17. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00017.

- Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, et al. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1792–1801.

- Hamer HM. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:104-19.

- Vahoutvin SA, Troost FJ, Kilkens TO. The effects of butyrate enemas on visceral perception in healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(9):952-76.

- S. Guglielmetti, D. Mora, M. Gschwender & K. Popp. Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life –– a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011.

- Alexander C. Ford, MBChB, MD et al. Efficacy of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Synbiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Chronic Idiopathic Constipation: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:1547–1561; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.202.

- Michael J Fox et al. Can probiotic yogurt prevent diarrhoea in children on antibiotics? A doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. BMJ Open 2015.

- Ki Cha B et al. The effect of a multispecies probiotic mixture on the symptoms and fecal microbiota in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46.

- Williams EA, Stimpson J, et al. Clinical trial: a multistrain probiotic preparation significantly reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a double-blind placebo controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009.

- Drouault-Holowacz S et al. A double blind randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination in 100 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008);

- Simrén M, Ohman L, Olsson J, Svensson U, Ohlson K, Posserud I, Strid H. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk containing three probiotic bacteria in patients with irritable bowel syndrome — a randomized, double-blind, controlled study . Aliment Pharmacol, Ther 2010.

- A Randomized Clinical Trial of Synbiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Dose-Dependent Effects on Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Fatigue Sang-Hoon Lee, Doo-Yeoun Cho at al, The Korean Academy of Family Medicine. Received: May 16, 2021,

- L. plantarum (Ducrotté P, Sawant P, Jayanthi V. Clinical trial: Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18.

- Rahman MZ, Ahmed DS, Mahmuduzzaman M. et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of trimebutine versus mebeverine in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome // Mymensingh Med J. 2014; 23 (1): 105–113.

- Trukhan D.I., Bagisheva N.V., Goloshubina V.V., Grishechkina I.A. Trimebutin in the treatment of gastrointestinal functional disorders // International Journal of Applied and Fundamental Research. 2016; 11(6):1072–1076.

- Tipikina M.Yu., Kornienko E.A. Pathogenetically based strategy for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. Questions of children's dietetics. 2014; 12(1): 22-27.

- Gülcan S Karabulut. The Incidence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Children Using the Rome III Criteria and the Effect of Trimebutine Treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19(1): 90-3. doi:10.5056.