Antispasmodics are a group of medications that can relieve spasms of internal organs and the associated pain syndrome.

Internal organs with a tubular structure (vessels, uterus, bronchi, ureters and bladder, intestines, bile ducts, etc.) contain a smooth muscle matrix - a layer of muscles located in the wall of the organ. Under physiological conditions, this smooth muscle regulates the lumen of the organ and is in constant tonic contraction.

Smooth muscle is involuntary. This means that we cannot control it using consciousness, such as striated muscles. We can voluntarily raise or lower our hand, but we cannot, through an effort of will, expand the bronchi or stop the contractions of the intestines. The smooth muscles are controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Autonomous because its functioning does not depend on our will.

The nerve endings of the autonomic nervous system do not adhere tightly to the smooth muscles; there is always a gap between them and the muscle, called a synapse. When the autonomic nerve is excited, under the influence of its impulse, a special substance called the mediator acetylcholine is released. This substance diffuses (penetrates) from the nerve ending to the muscle and activates the acetylcholine receptor on the smooth muscle cell membrane. At the same time, it is reduced. This is a normal physiological process.

In cases where the tone of the autonomic nervous system increases, for example, when the ureter is irritated by the spines of a kidney stone, more acetylcholine is produced, and the contraction of smooth muscles becomes excessively strong or chaotic. This leads to a painful sensation - spasm.

Spasm is a tonic, cramp-like contraction of internal organs that have smooth muscles and is manifested by specific pain. Spasm usually occurs due to inflammatory damage to the internal mucous membrane of a tubular organ.

During a spastic contraction of an organ, sensitive nerve endings and blood vessels are mechanically pinched, which leads to impaired circulation in the organ and pain. The pain syndrome caused by spasm is called colic.

Pharmacological action and its mechanism

Antispasmodic drugs can eliminate spasms through two mechanisms. The first mechanism is that the drug binds to the same receptor on smooth muscle as the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, but does not activate the receptor, but blocks it by simply occupying the acetylcholine site. The excess amount of acetylcholine cannot interact with its receptors, and the smooth muscle relaxes. This action is a neurotropic antispasmodic effect. Neurotropic because it affects the autonomic nervous system, making its activity ineffective.

The second mechanism by which antispasmodics can act is through the penetration of the drug into the smooth muscle cell, which changes its contractile physiology and makes its contraction ineffective. In this case, an antispasmodic effect will develop. This type of action is called the myotropic antispasmodic effect of gr. myos muscle and thropos direction of action.

Antispasmodics are classified according to the mechanism of action indicated above, since the mechanism of action is associated with well-predicted therapeutic and side effects.

Antispasmodic therapy for IBS

So, based on the diagnostic criteria for IBS, abdominal pain and discomfort are its cardinal symptoms, the origin of which is traditionally attributed, among other things, to spasm of the smooth muscle wall of the intestine. And although data on the study of this issue remain controversial, numerous publications and clinical studies confirm that an excessive response of the motility of the small and colon to external stimuli is associated with the manifestation of pain and discomfort in IBS [4–6, 9].

The group of antispasmodics includes several classes of drugs that are different in their mechanism of action - antimuscarinics, smooth muscle relaxants, anticholinergics, as well as such unique drugs as pinaveria bromide - a selective calcium channel blocker, and trimebutine - a peripheral agonist of opiate receptors [21] .

The use of anticholinergic drugs, taking into account their mechanism of action, is possible in cases of IBS with a predominance of pain in combination with defecation disorders - mostly with diarrhea. However, side effects common to this group of drugs, such as dry mouth, dizziness, blurred vision, urinary retention, and central effects (especially in the elderly), significantly limit their use in clinical practice, and given the high risk of developing constipation, they even prevent them prescription for IBS with a predominance of constipation is inappropriate [14, 18].

Due to the lack of international high-quality studies examining specific antispasmodics, it is possible to evaluate the effectiveness of drugs of this class in IBS using systematic reviews and meta-analyses. A special commission of the American College of Gastroenterology studied this issue by analyzing 22 clinical studies. It was found that, in general, each study contained a fairly large number of methodological errors regarding the diagnostic criteria used, inclusion criteria, drug dosage regimen and duration of therapy, and assessment of end points. Additionally, only 3 studies included more than 100 patients. Given these limitations, data from 1778 patients with IBS were analyzed. Pooled results showed that the risk ratio for failure of antispasmodics compared with placebo was 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI] - 0.57-0.81), and the NNT rate (number of patients who need to be treated to achieve benefit) one of them) was equal to 5. When assessing the risk of developing adverse events when taking antispasmodics, it was revealed that they were observed in 1379 patients. Given the significant heterogeneity of this group of patients, the hazard ratio for adverse events was 1.62 (95% CI 1.05–2.50) and the NNT was 18 (95% CI 7–217).

Publishing the results of a meta-analysis in 2009, the panel concluded: “Some antispasmodics (hyoscine, cimetropium and pinaveria bromide) may provide short-term relief of pain or discomfort in IBS (level of evidence 2C), but there is no evidence of long-term effectiveness ( level of evidence 2B), evidence of safety and tolerability is limited (level of evidence 2C)” [3].

Similar conclusions were made in a Cochrane systematic review published in 2011, which, based on a study of meta-analyses, compared the effectiveness of using various representatives of the group of antispasmodics with placebo [19]. The main criteria were the effect of the drugs on abdominal pain and improvement in general condition. As a result, pinaverium bromide confirmed its effectiveness in both cases [3, 19]. In Russia, pinaveria bromide is registered under the trade name “Dicetel ®” and in a dosage of 100 mg 2 times a day is intended to help patients with IBS to relieve manifestations of visceral hypersensitivity.

Thus, antispasmodics have been and remain the basis of IBS therapy. Moreover, their use is advisable from the standpoint of not only relieving spastic intestinal reactions, but also influencing visceral hypersensitivity as one of the main pathogenetic links of the syndrome by reducing the sensitivity of nociceptors.

Literature

1. Agreus I, Svardsudd K, Nyreu O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology 1995;109:671–80. 2. Barbara G, Stanghellini V, DeGiorgio R, et al. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004: 126:693–702. 3. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104(1):S1–35. 4. Chey WY, Jin HO, Lee MH, et al. Colonic motility abnormality in patients with irritable bowel syndrome exhibition abdominal pain and diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96(5):1499–506. 5. Clemens CH, Samsom M, Roelofs JM, et al. Association between pain episodes and high amplitude propagated pressure waves in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(8):1838–43. 6. Drossman DA, Camileri M, Mayer EA, et al. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;123(6):2108–31. 7. Drossman DA. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and the Rome III Process. Gastroenterology 2006;130(5):1377–90. 8. Drossman DA, Morris CB, Hu Y, et al. A prospective assessment of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome: defining an alternator. Gastroenterology 2005;128:580–89. 9. Fukudo S, Kanazawa M, Kano M, et al. Exagerrated motility of the descending colon with repetitive distention of the sigmoid colon in patient with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2002;37(14):145–50. 10. Guilera M, Balboa A, Mearin F. Bowel habit subtypes and temporal patterns in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005:100:1174–84. 11. Heaton KW, O'Donnell LJD, Braddon FEM, at al. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a British urban community: consulters and nonconsalters. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1962–67. 12. Holzer P. Tachykinin Receptor Antagonists: Silencing Neuropeptides with a Role in the Disturbed Gut. A Basis for Understanding Functional Diseases. Edited by R. Spiller and D. Grundy Blackwell Publishing, 2004. 13. Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, et al. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr 1996;129(2):220–26. 14. Irritable colon syndrome treated with an antispasmodic drug. Practitioner 1976;217(1298):276–80. 15. Locke GR III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1766–78. 16. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional Bowel Disorders. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and the Rome III Process. Gastroenterology 2006;130(5): 1377–90. 17. Mearin F, Balboa A, Badia X, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes according to bowel habit: revisiting the alternating subtype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:165–72. 18. O'Donnell LJD, Virjee J, Heaton KW. Detection of pseudodiarrhoea by simple clinical assessment of intestinal transit rate. Br Med J 1990; 300:439–40. 19. Page JG, Dirnberger GM. Treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome with Bentyl (dicyclomine hydrochloride). J Clin Gastroenterol 1981;3(2):153–56. 20. Ruepert T, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 8. 21. Talley NJ, Weaver AI, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LI. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidimiol 1992;136:165–77. 22. Talley NJ. Pharmacologic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(4):750–58. 23. Taub E, Cuevas JL, Cook EW, Crowell M, Whitehead WE. Irritable bowel syndrome defined by factor analysis, gender and race comparisons. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:2647–55.

About the authors / For correspondence

Mayev Igor Veniaminovich – corresponding member. RAMS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases and Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, Moscow State Medical University. Cheremushkin Sergey Viktorovich – Candidate of Medical Sciences, assistant at the Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases and Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, Moscow State Medical University. e-mail; Kucheryavy Yuriy Aleksandrovich – Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases and Gastroenterology of the State Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education MGMSU. Email; Cheremushkina Natalya Vasilievna – Candidate of Medical Sciences, assistant at the Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases and Gastroenterology at Moscow State Medical University. e-mail

Basics of therapy and application features

Not all antispasmodics have the same effect on certain organs. Some of them act predominantly on smooth muscles in some organs, and have no or almost no effect on smooth muscles in other organs. This selectivity of action is called selectivity.

For example, atropine, belladonna extract, papaverine and drotaverine, universal antispasmodics, bendazole acts primarily on blood vessels, theophylline primarily on the bronchi, mebeverine and prifinium bromide primarily on the organs of the gastrointestinal tract. Depending on the direction of action of the antispasmodic, it is prescribed for a particular pathology.

Neurotropic and myotropic antispasmodics, despite the fact that both relieve spasms of internal organs, they have common positive and negative aspects. For example, neurotropic antispasmodics cause dry mucous membranes and may cause constipation. Myotropic antispasmodics do not have such side effects, but they dilate blood vessels and lower blood pressure. Because of this, they are prescribed with caution to people with low blood pressure, or they may be contraindicated for them. Patients receiving medications for high blood pressure may require dose adjustment of antihypertensive drugs when prescribed a myotropic antispasmodic. Neurotropic antispasmodics do not have such disadvantages.

A positive feature of antispasmodics is their inability to mask threatening symptoms in the abdominal area, unlike analgesics. This means that if there is a serious pathology of the abdominal cavity, for example, inflammation of the peritoneum, the use of an antispasmodic will not mask this condition. The pain will persist despite the use of an antispasmodic. In this case, it is necessary to urgently seek medical help.

In any case, antispasmodic drugs can only be used after consulting a doctor, or if the drug is over-the-counter, after consulting a pharmacist.

Epidemiology of IBS

Data on the prevalence of IBS are based mainly on large studies conducted in the US and UK, while data from developing countries remain sparse. When comparing data from epidemiological studies around the world, clear differences are found. The prevalence of IBS also varies widely among different populations within a country [1, 11, 20]. It is not completely known what causes these differences: race, socioeconomic status, level of development of the country, different interpretations of the definition of IBS, or the methodology used?

Published data suggest that the incidence of IBS averages 1% per year.

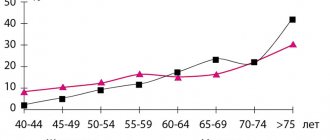

Symptoms of IBS are common in all age groups, with the onset of symptoms usually occurring in young adulthood [13, 23]. The average age of patients with IBS is 24–41 years. In the United States, the prevalence of IBS symptoms decreases after middle age, according to one national study. Symptoms of IBS throughout the world are more common among women, with a male to female ratio of approximately 1:2 among patients. This fact has been noted regardless of the diagnostic criteria used [23].

Convulsions

You might think that seizures occur only with epilepsy. Therefore, when they appear, anticonvulsants are definitely needed. In addition to epilepsy, there may be many other conditions that have nothing to do with it, but which may be accompanied by seizures:

- Cerebrovascular disease, age over 75 years, and hemorrhagic strokes often cause the onset of acute symptomatic seizures.

- Traumatic brain injuries.

- Infectious diseases of the central nervous system (meningitis, encephalitis, HIV infection).

- Oxygen starvation of the brain.

- Intoxication of the body.

- Taking medications.

- Acute metabolic disorders, for example, hypoglycemia in the treatment of diabetes mellitus, electrolyte imbalance.

- Withdrawal syndrome when stopping alcohol consumption.

- Taking large doses of alcohol.

- Taking psychotropic drugs (psychotropic stimulants - cocaine, crack, ecstasy).

- Temperatures above 38.5°C in children under 7 years of age can cause febrile seizures.

- Liver failure.

- Parkinson's disease.

Therefore, self-administration of anticonvulsants without a doctor’s prescription is prohibited. First you need to establish the cause of the problem and only then treat it.