Meningitis is a disease during which the membranes of the brain (meninges and subarachnoid space) become inflamed. It is caused by viruses and bacteria, depending on this the course of the disease occurs. In any case, this is a dangerous disease that requires medical treatment. It can lead to infection of the bloodstream or brain, as well as sepsis, which can be fatal.

Bacterial meningitis is believed to be more severe. If this form is diagnosed, the patient requires emergency medical care. In patients with viral meningitis, the symptoms and course of the disease are milder, but treatment is also in a hospital.

Meningitis in adults and children can have different symptoms, so next we will look at these two groups separately.

According to statistics, 90% of meningitis cases are children. In adults, those bacteria and viruses that can cause meningitis provoke the appearance of sore throat or tonsillitis. In some cases, the infection reaches the brain, affecting it and causing inflammation. Meningitis can also be a complication after sinusitis, tuberculosis and other similar diseases.

Key Facts

- Meningitis is a severe disease with a high mortality rate, leading to serious long-term complications.

- Meningitis remains one of the world's greatest health problems.

- Epidemics of meningitis occur throughout the world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Meningitis can be caused by many microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites.

- Bacterial meningitis is of particular concern. About one in ten patients die from this type of meningitis, and one in five develop severe complications.

- The most effective way to provide long-term protection against the disease is through safe and inexpensive vaccines.

This fact sheet focuses on the four main causes of acute bacterial meningitis:

- neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus)

- streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus)

- haemophilus influenzae (hemophilus influenzae)

- streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus)

Worldwide, more than half of all fatal cases of meningitis are caused by these bacteria, which also cause a number of other serious illnesses such as sepsis and pneumonia.

Other common causes of meningitis include other bacteria, such as mycobacterium tuberculosis, salmonella, listeria, streptococcus and staphylococcus, some viruses, such as enteroviruses and mumps virus, some fungi, especially cryptococcus, and parasites, such as amoebas.

What is this?

Meningitis (from the Latin meninx - “brain membrane”, suffix -itis - “inflammation”) is an inflammation of the membranes of the brain and spinal cord.

It is the membranes, and not the brain tissue itself. Inflammation of the brain is encephalitis (from the Latin encephalon - “brain”, suffix -itis - “inflammation”).

The brain has three membranes:

- hard;

- arachnoid (arachnoid);

- soft (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Meninges of the brain.

Source: SVG by Mysid, original by SEER Development Team [1], Jmarchn / Wikipedia (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license) The dura mater is adjacent to the inner surface of the skull. It consists of two leaves: outer and inner. The outer leaf is tightly adjacent to the inner surfaces of the bones of the vault and base of the skull, the inner leaf forms dense outgrowths of this shell into the cranial cavity, which play the role of a frame for the brain and divide it into several sections. Between the leaves there are important formations - venous sinuses. They collect blood, which flows from the brain, enters the jugular veins and then into the heart through the superior vena cava.

The arachnoid membrane is thin, it occupies an intermediate position between hard and soft and connects them to each other.

Finally, the pia mater is loose and covers the brain, extending into all its grooves and crevices. In the thickness of the soft shell there are a large number of vessels that nourish the brain tissue.

Most often (perhaps due to the abundant blood supply), it is the pia mater that becomes inflamed. However, inflammation of the dura and arachnoid membranes also occurs. If both the arachnoid and soft membranes are inflamed at the same time, the disease is called leptomeningitis, if we are talking only about the hard membrane - pachymeningitis.

The spinal cord also has dura, arachnoid and pia mater. In structure, they are almost no different from the membranes of the brain. Their inflammation is also called meningitis. It is dangerous because it can spread to the tissue of the spinal cord itself. However, these will be different pathological conditions with their own complications.

Who is at risk?

Meningitis affects people of all ages, but young children are most at risk. Newborns are at greatest risk of infection with group B streptococcus, and young children with meningococcus, pneumococcus and haemophilus influenzae. Adolescents and young adults are at greater risk for meningococcal disease, while older adults are at greater risk for pneumococcal disease.

Residents of all regions of the world are at risk for meningitis. The greatest disease burden is found in a region of sub-Saharan Africa known as the “African meningitis belt,” which is at particularly high risk for epidemics of meningococcal as well as pneumococcal meningitis.

The greatest risk occurs in settings where people are in close contact, such as large gatherings, refugee camps, overcrowded housing, or student, military, and other professional environments. Immunodeficiency associated with HIV infection or complement deficiency, immunosuppression, active or passive smoking can also increase the risk of developing various types of meningitis.

Causes

There are many reasons why inflammation can occur.

All of them are divided into two large groups: infectious and non-infectious.

Infectious causes

Pathogens that can cause meningitis include:

- bacteria (meningococcus, pneumococcus);

- viruses (enteroviruses, herpesviruses);

- mushrooms (candida);

- protozoa (malarial plasmodium, toxoplasma).

The most common are bacterial and viral meningitis. Protozoal infections are usually recorded only in certain regions, and fungal infections are typical for people with sharply reduced immunity, for example, patients with HIV infection in the last stages.

In this case, the infection can penetrate to the meninges in several ways. Thus, with an existing purulent infection of the nasal sinuses, inflammation of the middle ear or purulent pathology of the teeth, it can spread by contact to nearby tissues and organs. In the presence of an open craniocerebral injury or a crack in the skull bones, the pathogen can also penetrate with the lymph flow along the nerve endings. However, most often the infection enters the cranial cavity through the bloodstream.

A healthy person becomes infected from a carrier of the infection through airborne droplets (through coughing, sneezing and kissing), through contaminated food and untreated water. In some cases, the pathogen is transmitted from mother to fetus, or as a result of the bite of an insect vector (for example, in the case of malaria).

When it enters the body, the pathogen enters the blood and immediately causes inflammation of the meninges (primary meningitis), or affects other organs and tissues, and then through the bloodstream reaches the meninges and brain (secondary meningitis).

How often do people get meningitis and how dangerous is it?

Every year, about 2.8 million cases of meningitis are registered worldwide.1 More than 300 thousand become fatal, of which a third are children under 5 years of age.

Every fifth survivor of the disease has complications: behavioral problems, incoordination, hearing loss, paralysis, seizure activity, etc. The highest morbidity and mortality rates are observed in the “meningitis belt” located in sub-Saharan Africa, from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east. This small area accounts for more than 10% of all reported cases of the disease (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Incidence of meningitis in the world (number of cases per 100 thousand population), 2021. Source: WHO

Bacterial meningitis

As a rule, it is the most difficult. The main pathogens: meningococcus, pneumococcus, staphylococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, listeria, tubercle bacillus.

Most epidemics (including outbreaks in the meningitis zone) are caused by meningococcus, or the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis.

Meningococcus causes different forms of infections:

- asymptomatic carriage of bacteria, when a person does not even suspect that he is infected. According to research, from 5 to 10% of the total population of the planet become carriers4.

- nasopharyngitis, occurring with symptoms of a typical cold;

- meningitis;

- meningococcemia (meningococcal sepsis).

Meningococcal meningitis and sepsis can often be characterized by a lightning-fast course, then no more than a day passes from the onset of the disease to death. Therefore, at the first signs of meningococcemia or with the development of meningitis, when the causative agent of the disease has not yet been identified, it is necessary to seek medical help as soon as possible and prescribe antibiotics. In this case, the count goes to hours and even minutes.

Carriage of meningococcus, as well as increased sensitivity to the pathogen, often occurs among members of the same family. Therefore, if there are several children in a family, and one of them has already suffered meningococcal meningitis, it is recommended to examine and, if necessary, treat and vaccinate the remaining children, as well as their parents.

Another bacterium that also often causes meningitis is Streptococcus pneumoniae, also known as pneumococcus. Its difference is that in addition to meningitis, it causes sinusitis, otitis, pneumonia and other diseases. In this case, the infection can spread over time and develop into secondary meningitis. That is why it is important to begin treatment of pneumococcal diseases as early as possible and not wait for the pathological process to worsen.

Viral meningitis

Viral meningitis occurs almost twice as often as bacterial meningitis. However, they are easier. With a mild form of viral meningitis, the symptoms go away on their own, without specific treatment, within 7-10 days. The mortality rate from viral meningitis with proper treatment is 5-13%³.

Among viruses, meningitis is most often caused by enteroviruses (Coxsackie viruses and echoviruses) - up to 80% of all cases5 - and herpes viruses.

Fungal meningitis

Most often found in people with immunodeficiencies. For example, cryptococcal meningitis in AIDS or candidal meningitis caused by the Candida fungus, which normally lives on a person’s skin and inside the body and does not cause any problems.

Fungal meningitis develops when an infection spreads from the lungs to the brain and spinal cord and requires mandatory use of antifungal drugs. It is not transmitted from person to person.

Protozoal meningitis

It is also rare and mainly occurs in people with weakened immune systems. The most common pathogens are Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum.

Separately, parasitic meningitis is distinguished.

Why don't all infections end in meningitis?

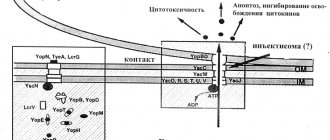

Despite the abundance of infectious agents, meningitis occurs infrequently. Meningococcal infection often occurs asymptomatically or in the form of nasopharyngitis; enteroviruses and herpesviruses also affect other organ systems. This happens for two reasons. Firstly, a healthy immune system has time to cope with the infectious agent before any serious symptoms appear. Secondly, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) protects the brain from exposure to microbes. It is a physiological barrier between the blood and the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), consisting of various types of cells. It protects brain tissue from toxins, microorganisms, cells and active immune system molecules that circulate in the blood. Through it, nutrients needed by the brain are selectively supplied. If the BBB is weakened or damaged, its genetic characteristics, or with hereditary or acquired high sensitivity to the microorganism, the latter is able to penetrate the barrier. However, pathogens that account for the majority of cases of meningitis (meningococci, pneumococci, listeria, Haemophilus influenzae) have additional mechanisms for penetrating the protective barrier.

Non-infectious causes

Such meningitis is the most rare. This includes forms caused by non-infectious diseases or a specific reaction to a drug.

What non-communicable diseases can cause meningitis? For example, autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system begins to destroy the body’s own tissues: systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and others.

Meningitis can also occur:

- with ruptures of benign tumors (cysts) located in the brain area;

- when the membranes of the brain are damaged by a malignant tumor;

- brain and spinal cord injuries;

- after operations performed on the brain;

- reactive in response to medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, certain groups of antibiotics, etc.).

Mechanisms of transmission

The mechanisms of transmission of infection depend on the type of pathogen. Most of the bacteria that cause meningitis, such as meningococcus, pneumococcus and haemophilus influenzae, are present in the human nasopharyngeal mucosa. They are spread through respiratory and throat secretions. Group B streptococcus is often present in the intestinal or vaginal mucosa and can be transmitted from mother to child during childbirth.

Carriage of these organisms is usually harmless and leads to the formation of immunity to infection, but in some cases an invasive bacterial infection can develop, causing meningitis and sepsis.

Where does the disease come from?

By its origin, serous meningitis can be:

- Primary – brain damage directly from a viral or bacterial attack.

- Secondary - develops against the background of another disease that causes a weakened immune system.

The causative agents of the disease can be:

- viruses;

- bacteria;

- fungi.

According to medical statistics, among childhood morbidity, viral pathogens account for 80% of cases of serous meningitis. Children of preschool age - from three to six years old - are susceptible to inflammation of the meninges. Schoolchildren and adults to a lesser extent.

Acute serous meningitis is most often caused by enteroviruses. Among them, there are two main ones: the ECHO virus and the Coxsackie virus.

In more rare cases, the reasons are:

- Epstein-Bar virus (is the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis);

- cytomegalovirus;

- herpes;

- measles;

- influenza viruses (especially highly mutagenic ones).

In medicine, there are three ways of transmitting the disease:

- Contact – with a handshake and other touches by the wearer. In the latter, the virus is most often localized on the hands, skin lesions, mucous membranes of the mouth and eyes.

- Airborne - concentration of the virus in the respiratory tract. It is transmitted by inhaling air that contains saliva particles containing the pathogen in the form of an aerosol.

- Alimentary (fecal-oral) method - a susceptible organism ingests water contaminated with enteroviruses. In recent years, outbreaks of meningitis have become common in the summer, when the swimming season is in full swing. The infection, entering the child’s mouth with water, accumulates in the intestines. Later it is excreted in feces and again ends up in the water.

Enteroviruses retain their vital functions on food products for a long time. Personal hygiene, thorough washing of vegetables and fruits reduce the risk factor.

The incubation period of the disease varies from several hours (acute form) to several days. In this case, the first symptoms of serous meningitis in children may appear only a week after the direct infection.

Clinical signs and symptoms

Depending on the pathogen, the incubation period can vary and for bacterial meningitis range from two to 10 days. Since bacterial meningitis is often accompanied by sepsis, the described clinical signs and symptoms apply to both pathologies.

Clinical signs and symptoms:

- severe headaches

- stiff neck or neck pain

- severe increase in body temperature

- photophobia

- confusion, drowsiness, coma

- convulsions

- rash

- joint pain

- cold extremities

- vomit

Infants may have the following symptoms:

- loss of appetite

- drowsiness, lethargy, coma

- irritability, crying when moving

- difficulty breathing, wheezing

- elevated body temperature

- stiff neck muscles

- swollen fontanel

- characteristic high-pitched scream

- convulsions

- vomit

- rash

- pale or blotchy skin

How to protect yourself from illness

All parents should pay attention to the prevention of serous meningitis in children. In the summer, you should listen to local news - if an outbreak of meningitis follows after visiting open water, you should not allow your child to swim there.

Measures to combat the disease are generally reduced to maintaining hygiene rules:

- Drink boiled or specially purified water. This rule should be taken especially seriously by those who live in low-lying areas where wastewater may enter the water intake.

- Follow the rules of personal hygiene - be sure to wash your hands after visiting the toilet and before eating.

- Wash vegetables and fruits before eating (especially in the summer). Products can additionally be doused with boiling water - enteroviruses are afraid of high temperatures.

- Meningitis can develop against the background of other viral diseases - measles, mumps, influenza and even common ARVI. Therefore, be attentive to the follow-up treatment and recovery of your child after any such illness.

- If a baby has a weak immune system, he should not come into contact with rodents (even domestic ones), as they are considered carriers of serous meningitis pathogens.

Meningitis is a complex disease. Due to the carelessness of parents, the disease often has the most disastrous consequences. But if you raise the alarm in time and go to a medical facility, serous meningitis will go away quite quickly - in 10-12 days. And don’t forget about prevention – it’s better not to get sick at all.

When the first symptoms of the disease appear, contact an infectious disease specialist online or at a good infectious diseases hospital.

For more information about meningitis in children, watch the video:

This article has been verified by a current qualified physician, Victoria Druzhikina, and can be considered a reliable source of information for site users.

Bibliography

1. https://niidi.ru/dotAsset/e3e1899f-a522-4aa4-acd2-f28dedca3bc0.pdf

Rate how useful this article was

4 3 people voted, average rating 4

Did you like the article? Save it to your wall so you don’t lose it!

Prevention

The most effective way to reduce the burden of disease and mitigate the negative impact of meningitis on public health is to provide long-term protection against the disease through vaccination.

In the risk group for meningococcal meningitis and meningitis caused by group B streptococcus, antibiotics are also used for preventive purposes. Both vaccination and antibiotics are used to control epidemics of meningococcal meningitis.

Vaccination

Registered vaccines against meningococci, pneumococci and haemophilus influenzae have been on the market for many years. There are several different strains (also called serotypes or serogroups) of these bacteria, and vaccines aim to provide immunity to the most dangerous ones. Over time, great strides have been made in terms of coverage of different strains and availability of vaccines, but a universal vaccine against all these pathogens has not yet been developed.

Meningococci

There are 12 serogroups of meningococci, of which in most cases the causative agents of meningitis are bacteria of serogroups A, B, C, W, X and Y.

There are three types of vaccines:

- Polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines are used to prevent and respond to disease outbreaks: Such vaccines provide long-term immunity and also prevent the carriage of infection, thereby reducing the spread of infection and creating herd immunity.

- They are effective in protecting children under two years of age from the disease.

- These vaccines come in different forms: monovalent vaccines (serogroup A or C)

- quadrivalent vaccines (serogroups A, C, W, Y).

- combination vaccines (meningococcus serogroup C and haemophilus influenzae type b)

Global public health response: eliminating epidemics of group A meningitis in the African meningitis belt

Before the introduction of the conjugate vaccine against group A meningococcus as part of mass vaccination campaigns (since 2010) and its inclusion in the routine vaccination calendar (since 2021) in the countries of the African meningitis belt, this pathogen caused 80-85% of all meningitis epidemics. As of April 2021, 24 of the 26 countries in the meningitis belt have conducted mass prevention campaigns among children aged 1–29 years (nationally or in high-risk areas), and half of these have included the vaccine in their national routine schedules. vaccinations. Among the vaccinated population, the incidence of serogroup A meningitis has decreased by more than 99%, and no cases of serogroup A meningococcal disease have been identified since 2021. To avoid resurgence of epidemics, it is critical to continue efforts to include this vaccine in the routine immunization schedule and support high level of vaccination coverage.

Isolated cases and outbreaks of meningitis caused by meningococcal serogroups other than serogroup B continue to be reported. The introduction of multivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines is a public health priority to eliminate epidemics of bacterial meningitis in the African meningitis belt.

Pneumococcus

There are more than 97 known serotypes of pneumococci, 23 of which cause the majority of cases of pneumococcal meningitis.

- Conjugate vaccines are effective from 6 weeks of age for the prevention of meningitis and other severe pneumococcal infections and are recommended for vaccination of infants and children under 5 years of age, and in some countries, adults over 65 years of age, as well as representatives of certain risk groups. Two conjugate vaccines are used that protect against pneumococcal serotypes 10 and 13. New conjugate vaccines designed to protect against more pneumococcal serotypes are currently in development or have already been approved for vaccination in the adult population. Work continues to create protein-based vaccines.

- There is a polysaccharide vaccine designed to protect against 23 serotypes, however, like other polysaccharide vaccines, it is considered less effective than conjugate vaccines. It is used mainly for vaccination against pneumonia among people over 65 years of age, as well as members of certain risk groups. It is not used to vaccinate children under 2 years of age and is less effective in preventing meningitis.

Haemophilus influenzae

There are 6 known serotypes of haemophilus influenzae, of which the main causative agent of meningitis is serotype b.

- There are conjugate vaccines that provide specific immunity to haemophilus influenzae serotype b (Hib). They are a highly effective means of preventing disease caused by Hib and are recommended for inclusion in routine vaccination schedules for newborns.

Group B streptococcus

There are 10 known serotypes of group B streptococci, of which the most common causative agents of meningitis are streptococci types 1a, 1b, II, III, IV and V.

- Currently, work is underway to create conjugate and protein vaccines to prevent infection with group B streptococci in mothers and newborns.

Prophylactic use of antibiotics (chemoprophylaxis)

Meningococci

Timely administration of antibiotics to persons who have been in close contact with patients with meningococcal infection reduces the risk of transmission of infection. Outside the African meningitis belt, chemoprophylaxis is recommended for family members of patients who are in close contact with them. In countries with a meningitis belt, it is recommended to prescribe chemoprophylaxis to persons who have had close contacts with patients in the absence of an epidemic. The drug of choice is ciprofloxacin; Ceftriaxone is prescribed as an alternative.

Group B streptococcus

In many countries, it is recommended to identify mothers whose children are at risk for group B streptococcus. One way to achieve this goal is universal screening of pregnant women for carriage of group B streptococcus. To prevent group B streptococcal infection in newborns, mothers at risk are prescribed penicillin intravenously.

Personnel protection and patient isolation

To prevent airborne spread of infection, patients with meningococcal infection or meningitis of unknown etiology are isolated during the first 24 hours of antibiotic therapy. Infection of personnel can occur during tracheal intubation, CPR, and artificial ventilation. Standard precautions must be taken.

The need for prophylactic antibiotics should be considered for ICU staff if a patient is diagnosed with meningococcal meningitis. The likelihood of infection remains for 24 hours after antibiotics are prescribed. The chance of infection is higher among younger employees and people over 60 years old.

Use any of the following schemes:

1. Ciprofloxacin tablets, 500 mg twice a day. per day for 2 days;

2. Rifampicin tablets, 600 mg every 12 hours for 2 days.

Diagnostics

The initial diagnosis of meningitis is made by clinical examination followed by a lumbar puncture. In some cases, bacteria may be visible in the cerebrospinal fluid under a microscope. The diagnosis is supported or confirmed by culture of cerebrospinal fluid or blood samples, rapid tests, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. To select the correct measures to combat infection, it is important to identify the serogroup of the pathogen and conduct testing for its sensitivity to antibiotics. Molecular typing and whole-genome sequencing make it possible to identify more differences between strains and provide valuable information for making decisions regarding the necessary anti-epidemic measures.

Sources

- Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 [Electronic resource] // The Lancet. Neurology, 2021.

- Epidemiology of Meningitis Caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza [Electronic resource] // cdc.gov, 2021.

- Rebecca M. Cantu; Joe M Das. Viral Meningitis [Electronic resource] // NCBI, 2021.

- Meningitis [Electronic resource] // who.int

- What Do You Want to Know About Meningitis? [Electronic resource] // healthline.com, 2021.

- YouTube. Research and assessment of meningeal symptoms in a child.

- Clinical protocol for diagnosis and treatment. Meningitis in children and adults [Electronic resource] // rcrz.kz, 2021.

- Kenadeed Hersi; Francisco J. Gonzalez; Noah P. Kondamudi. Meningitis [Electronic resource] // NCBI, 2021.

Treatment

Without adequate treatment, meningitis is fatal in half of patients and should always be considered an emergency. Hospitalization is indicated for all patients with meningitis. As a rule, it is not recommended to isolate patients after 24 hours from the start of treatment.

For bacterial meningitis, treatment with appropriate antibiotics should be started as soon as possible. Ideally, a lumbar puncture should be performed before starting a course of antibiotics, as antibiotics may make it difficult to perform a cerebrospinal fluid culture. However, the type of pathogen can also be determined by testing a patient's blood sample, and prompt treatment remains a priority. A wide range of antibiotics are used to treat meningitis, including penicillin, ampicillin and ceftriaxone. During epidemics of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis, ceftriaxone is the drug of choice.

Prognosis of viral meningitis

For most adult patients with viral meningitis, the prognosis is good. In only 10% of cases, the disease can result in severe complications. Such complications include headache, asthenia, coordination disorders, memory impairment, inattention, and problems with concentration. However, all these symptoms of viral meningitis pass quite quickly - within a few weeks, less often - a couple of months. For children, the prognosis is less favorable, since the disease leads to serious complications such as intellectual impairment, mental retardation, and hearing loss.

Support and follow-up

The consequences of meningitis can have a huge negative impact on a person's life, their family and the local community, both financially and emotionally. Sometimes complications such as deafness, learning difficulties or behavioral disorders are not recognized by parents, carers or health professionals and therefore go untreated.

The consequences of meningitis often require long-term treatment. The permanent psychosocial impact of disability resulting from meningitis may create a need for medical care, educational assistance, and social and human rights support. Despite the high burden of meningitis on patients, their families and communities, access to services and support for these conditions is often insufficient, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Persons with disabilities due to meningitis and their families should be encouraged to seek services and advice from local and national disability societies and other disability-focused organizations where they can receive vital advice on their rights, economic opportunities and social life, so that people who have become disabled due to meningitis can live a full life.

Meningitis: which doctor treats it?

Since meningitis is most often an infectious disease, treatment is prescribed by infectious disease doctors . They also carry out diagnostics. Moreover, all this is done after the patient is hospitalized, i.e. in the infectious diseases department. Additionally, observation by a neurologist is necessary, since the infection affects the nervous system.

Even suspicion of meningitis requires immediate hospitalization until the causes are clarified . This disease has a very high mortality rate and an even higher rate of neurological complications. For prevention, you need to get vaccinated, maintain hygiene, and eat right. Be healthy!

Epidemiological surveillance

Epidemiological surveillance, from case detection to investigation and laboratory confirmation, is essential for successful control of meningococcal meningitis. Main objectives of surveillance:

- detection and confirmation of disease outbreaks;

- monitoring incidence trends, including the distribution and evolution of serogroups and serotypes;

- assessing the burden of disease;

- monitoring of pathogen resistance to antibiotics;

- monitoring the circulation, distribution and evolution of individual strains;

- assessing the effectiveness of strategies to control meningitis, in particular vaccine prevention programs.