Acute obstructive bronchitis is an acute inflammatory disease of the respiratory tract that affects the bronchi of medium and small caliber. It occurs with bronchial obstruction syndrome associated with bronchospasm, swelling of the bronchial mucosa and hypersecretion of mucus.

Acute obstructive bronchitis (ICD code 10 for acute bronchitis - J20) is more often diagnosed in young children.

Acute obstructive bronchitis is manifested by severe cough, shortness of breath and deterioration in general health

Causes and risk factors

The development of acute obstructive bronchitis in adults and children is caused by infection with the following microorganisms:

- rhinoviruses;

- adenoviruses;

- parainfluenza virus type 3;

- influenza viruses;

- respiratory syncytial viruses;

- viral-bacterial associations.

When conducting bacteriological research, chlamydia, mycoplasma, and herpes virus are often isolated in bronchial rinsing waters.

The prognosis is favorable. With adequate treatment, the disease ends in recovery within 7–21 days.

If you look at the medical histories of people suffering from obstructive bronchitis, you will notice that many of them have a history of indications of weakened immunity, frequent respiratory diseases, and increased allergies.

The combination of unfavorable environmental factors and hereditary predisposition provokes the development of an inflammatory process that affects small and medium-sized bronchi, as well as the surrounding tissues. This leads to disruption of the movement of cilia of ciliated epithelial cells. Subsequently, the ciliated cells are gradually replaced by goblet cells. Morphological changes in the bronchial mucosa are accompanied by changes in the composition of bronchial mucus, which leads to the development of mucostasis and obstruction (blockade) of small-caliber bronchi. This, in turn, provokes disturbances in the ventilation-perfusion ratio.

The content of lysozyme, interferon, lactoferon and other factors of nonspecific local immunity, which normally provide antibacterial and antiviral protection, decreases in bronchial mucus. As a result, pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses) begin to actively multiply in the viscous and thick secretion, which maintains the activity of inflammation.

In the pathological mechanism of development of bronchial obstruction, activation of cholinergic receptors of the autonomic nervous system is of no small importance, which leads to the occurrence of a bronchospastic reaction.

All the processes described above lead to spasm of the smooth muscles of the bronchi and swelling of their mucous membrane, hypersecretion of mucus.

If the body is highly allergenic, bronchitis can take a recurrent or chronic course and over time transform into asthmatic, and then into bronchial asthma.

Tracheobronchitis - symptoms and treatment

Diagnostic measures for acute tracheobronchitis are usually carried out on an outpatient basis by a pediatrician, therapist or pulmonologist; in case of allergic etiology, consultation with an allergist is indicated. The diagnosis is usually clinical, since with acute tracheobronchitis in most cases there is no need for laboratory or instrumental examination. Additional examinations are required in two cases: if the disease drags on, or if it is an exacerbation of chronic tracheobronchitis with a suspected complicated course.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of acute tracheobronchitis: low-grade fever (37.1-38.0 °C), moderately severe general intoxication syndrome, cough, diffuse dry and variable moist rales in the lungs.

X-ray of the lungs is important to exclude complications, in particular pneumonia. Also characteristic is the patient’s appearance, high fever, tachypnea (increased breathing rate) and, as a result, insufficient oxygen supply to the blood, so-called hypoxemia.

To exclude bacterial complications, a study of sputum (general analysis, culture for microflora) and peripheral blood (clinical blood test, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin) is carried out. To confirm the allergic nature, an allergological examination is carried out (determination of specific immunoglobulins E, skin allergy tests).

Patients complaining of shortness of breath should undergo pulse oximetry (a method for determining the degree of oxygen saturation of the blood) to exclude hypoxemia. Nasopharyngeal swabs can be tested for influenza and whooping cough if such pathology is suspected.

To diagnose chronic bronchitis, a medical history is carefully collected to exclude complications, spirometry (a study of external respiration function with measurement of lung volume) and, if necessary, a computed tomogram of the chest organs are performed. In the presence of concomitant pathology of the cardiovascular system, echocardiography may be recommended [8][9].

Differential diagnosis of prolonged cough should be carried out in people with cardiovascular pathology who are taking certain medications that can cause cough (for example, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors).

Particular caution should be exercised in relation to smokers over 50 years of age and people working in hazardous industries. Sometimes a consultation with a gastroenterologist is required to rule out gastroesophageal reflux , which is the cause of prolonged cough in about 40% of people. Gastroesophageal reflux is a condition that occurs when the motor-evacuation function of the gastrointestinal tract is disrupted and is characterized by regularly repeated reflux of stomach and duodenal contents into the esophagus and oral cavity, manifested by cough, hoarseness, and shortness of breath. Also, if it is difficult to diagnose the cause of a prolonged cough, consultation with an otolaryngologist is necessary to exclude postnasal drip (draining of excess mucus down the back wall of the throat) and chronic sinusitis .

Symptoms

The disease begins acutely and is characterized by the development of bronchial obstruction and infectious toxicosis, the signs of which are:

- general weakness;

- headache;

- low-grade fever (i.e. not exceeding 38 °C);

- dyspeptic disorders.

In the clinical picture of acute bronchitis with signs of obstruction, respiratory disorders play a leading role. Patients are bothered by an obsessive cough that worsens at night. It may be dry or moist, with mucous discharge. In adults with hypertension, streaks of blood may be present in the sputum.

Shortness of breath occurs and intensifies. During inhalation, the wings of the nose inflate, and auxiliary muscles (abdominal muscles, shoulder girdle, neck) take part in the act of breathing.

When auscultating the lungs, pay attention to a whistling extended exhalation and well-audible (often even at a distance) dry rales.

Acute bronchitis

Features of the clinical picture of acute bronchitis depend on the causative factor, the nature, prevalence and severity of pathological changes, the level of damage to the bronchial tree, and the severity of the inflammatory process.

The disease is characterized by an acute onset with signs of damage to the upper and lower respiratory tract and intoxication. Acute bronchitis of infectious etiology is preceded by symptoms of ARVI - nasal congestion, runny nose, sore and sore throat, hoarseness. The development of general intoxication in acute bronchitis is manifested by chills, increased body temperature to subfebrile levels, weakness, fatigue, headache, sweating, pain in the muscles of the back and limbs. With a mild course of acute bronchitis, there may be no temperature reaction. Acute bronchitis caused by measles, rubella and whooping cough is accompanied by symptoms characteristic of the underlying disease.

The leading symptom of acute bronchitis is a dry, painful cough that appears from the very beginning and lasts throughout the disease. The cough is paroxysmal, rough and sonorous, sometimes “barking”, increasing the feeling of rawness and burning behind the sternum. Due to overstrain of the pectoral muscles and spastic contraction of the diaphragm during a forced cough, pain appears in the lower chest and abdominal wall. The cough is accompanied by the release of scanty and viscous sputum at first, then the nature of the sputum gradually changes: it becomes less viscous and passes more easily, and may have a mucopurulent character.

A severe and protracted course of acute bronchitis is observed during the transition of the inflammatory process from the bronchi to the bronchioles, when a sharp narrowing or even closure of the bronchiolar lumen leads to the development of severe obstructive syndrome, impaired gas exchange and blood circulation. When bronchiolitis is added to acute bronchitis, the patient’s condition suddenly worsens: fever, pale skin, cyanosis, severe shortness of breath (40 or more breaths per minute), painful cough with scanty mucous sputum, first excitement and anxiety, then symptoms of hypercapnia (lethargy, drowsiness) are noted. ) and cardiovascular failure (low blood pressure and tachycardia).

Acute allergic bronchitis is characterized by a connection between the disease and exposure to an allergen, a pronounced obstructive syndrome with paroxysmal cough, and the release of light, glassy sputum. The development of acute bronchitis, caused by inhalation of toxic gases, is accompanied by chest tightness, laryngospasm, suffocation and painful cough.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of acute bronchitis with obstruction is based on the clinical picture and physical examination of the patient, the results of instrumental and laboratory research methods:

- Auscultation of the lungs. Patients exhibit harsh breathing and whistling dry rales. After coughing, the number and tone of wheezing changes.

- X-ray of the lungs. The x-ray shows an increase in the roots of the lungs and bronchial pattern, emphysema of the pulmonary fields.

- Therapeutic and diagnostic bronchoscopy. During the procedure, the doctor examines the bronchial mucosa, collects sputum for laboratory testing and, if necessary, can perform bronchoalveolar lavage.

- Bronchography. This diagnostic procedure is indicated for suspected bronchiectasis.

- Study of external respiration function (RPF). Pneumotachometry, peak flowmetry, and spirometry are of greatest importance in diagnosis. Based on the results obtained, the reversibility and degree of bronchial obstruction and the degree of impairment of pulmonary ventilation are determined.

- Laboratory research. The patient undergoes general urine and blood tests, a biochemical blood test (fibrinogen, total protein and protein fractions, glucose, creatinine, aminotransferases, bilirubin are examined). To assess the degree of respiratory failure, determination of the acid-base state of the blood is indicated.

If you look at the medical histories of people suffering from obstructive bronchitis, you will notice that many of them have a history of indications of weakened immunity, frequent respiratory diseases, and increased allergies.

Acute bronchitis with obstruction requires differential diagnosis with a number of other respiratory diseases:

- bronchial asthma;

- bronchiectasis;

- pulmonary embolism (PE);

- lungs' cancer;

- pulmonary tuberculosis.

Acute bronchitis: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, rational therapy

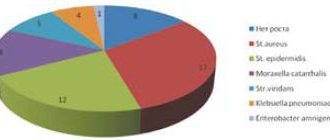

One of the causes of cough that first appeared in a patient after an acute respiratory viral infection (ARVI) is acute bronchitis (AB). Despite the apparent simplicity of the clinical symptoms of the disease, many medical errors are made in the diagnosis and treatment of this pathology. Definition Acute bronchitis (ICD-10: J20) is an acute/subacute disease of predominantly viral etiology, the leading clinical symptom of which is a cough that lasts no more than 2–3 weeks. and usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms and symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection [1]. The Australian Society of General Practitioners guidelines specify the following diagnostic criteria for the disease: acute onset cough lasting less than 14 days, accompanied by at least one of the symptoms of sputum production, shortness of breath, wheezing or chest discomfort [ 2]. Pathogenesis There are several stages in the pathogenesis of OB [3]. The acute stage is caused by the direct effect of the pathogen on the epithelium of the mucous membrane of the airways, which leads to the release of cytokines and activation of inflammatory cells. This stage is characterized by the appearance 1–5 days after “infectious aggression” of systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise and muscle pain. The protracted stage is characterized by the formation of transient hypersensitivity (hyperreactivity) of the epithelium of the tracheobronchial tree. Other mechanisms for the formation of bronchial hypersensitivity are also discussed, for example, an imbalance between the tone of the adrenergic and nervous cholinergic systems. Clinically, bronchial hypersensitivity manifests itself within 1 to 3 weeks. and is manifested by cough syndrome and the presence of dry wheezing on auscultation. The following pathophysiological mechanisms play a role in the development of OB: • decreased effectiveness of physical protective factors; • change in the ability to filter inhaled air and free it from coarse mechanical particles; • violation of thermoregulation and air humidification, sneezing and coughing reflexes; • disturbance of mucociliary transport in the respiratory tract. Deviations in the mechanisms of nervous and humoral regulation lead to the following changes in bronchial secretions: • disruption of its viscosity; • violation of the content of lysozyme, protein and sulfates. The course of inflammation in the bronchi is also affected by vascular disorders, especially at the level of microcirculation. Viruses and bacteria penetrate the bronchial mucosa most often aerogenously, but hematogenous and lymphogenous routes of penetration of infection and toxic substances are possible. It is known that influenza viruses have a bronchotropic effect, manifested by damage to the epithelium and disruption of bronchial trophism due to damage to nerve conductors. Under the influence of the general toxic effect of the influenza virus, phagocytosis is inhibited, immunological defense is disrupted, as a result, favorable conditions are created for the life of the bacterial flora located in the upper respiratory tract and ganglia. Based on the nature of inflammation of the bronchial mucosa, the following forms of OB are distinguished: catarrhal (superficial inflammation), edematous (with swelling of the bronchial mucosa) and purulent (purulent inflammation) (Fig. 1). Epidemiology The incidence of OB is high, but it is extremely difficult to judge its true level, because often OB is nothing more than a component of the infectious process in viral lesions of the upper respiratory tract. Indeed, OB is most often hidden under the guise of ARVI or acute respiratory disease (ARI). This is understandable, because The cause of OB is most often viruses, which easily “open the door” for bacterial flora. The epidemiology of OB is related to the epidemiology of the influenza virus. Typical peaks in the growth of the disease and other respiratory viral diseases are more often observed in late December and early March [4, 5]. Risk factors Risk factors for the development of OB are: • allergic diseases (including bronchial asthma (BA), allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis); • hypertrophy of the nasopharyngeal and palatine tonsils; • immunodeficiency states; • smoking (including passive); • elderly and children's age; • air pollutants (dust, chemical agents); • hypothermia; • foci of chronic upper respiratory tract infections. Etiology of acute bronchitis The main role in the etiology of bronchitis belongs to viruses. According to AS Monto et al., the development of OB in more than 90% of cases is associated with a respiratory viral infection and in less than 10% of cases with a bacterial infection [6]. Among the viruses in the etiology of OB, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza, RS virus, coronavirus, adenovirus, and rhinovirus play a role. Bacterial agents that cause the development of OB include Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae. Rarely, the causes of OB are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis. Table 1 provides characteristics of OB pathogens. Classification There is no generally accepted classification of OB; research is still underway to form it. Conventionally, we can distinguish etiological and functional classification signs of the disease: • viral; • bacterial. Other (rare) etiological options are also possible: • toxic; • burn. Toxic and burn OB are considered not as independent diseases, but as a syndrome of systemic damage within the framework of the corresponding nosology. According to ICD-10, depending on the etiology, OB is classified as follows: • J20.0 Acute bronchitis caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae; • J20.1 Acute bronchitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae; • J20.2 Acute bronchitis caused by streptococcus; • J20.3 Acute bronchitis caused by the Coxsackie virus; • J20.4 Acute bronchitis caused by parainfluenza virus; • J20.5 Acute bronchitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus; • J20.6 Acute bronchitis caused by rhinovirus; • J20.7 Acute bronchitis caused by echovirus; • J20.8 Acute bronchitis caused by other specified agents; • J20.9 Acute bronchitis, unspecified. Clinic and diagnosis Clinical manifestations of OB often have similar symptoms to other diseases. The disease can begin with a sore throat, chest discomfort, and a dry, painful cough. At the same time, body temperature rises, general malaise appears, and appetite disappears. On the 1st and 2nd days there is usually no sputum. After 2-3 days, the cough begins to be accompanied by sputum discharge. Diagnosis of OB involves excluding other acute and chronic diseases with similar syndromes. A preliminary diagnosis is made by exclusion and is based on the clinical picture of the disease [3]. Table 2 shows the frequency of clinical signs of OB in adult patients. The most common clinical symptom of OB is cough. If it lasts more than 3 weeks, it is customary to talk about persistent or chronic cough (which is not equivalent to the term “chronic bronchitis”), which requires differential diagnosis. The diagnosis of OB is made in the presence of an acute cough that lasts no more than 3 weeks. (regardless of the presence of sputum), in the absence of signs of pneumonia and chronic lung diseases, which may cause cough [3]. The diagnosis of acute bronchitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Laboratory data When a patient visits a clinic, they usually do a general blood test, in which no specific changes in OB are noted. Possible leukocytosis with a band shift to the left. For clinical signs of bacterial etiology of OB, bacterioscopic (Gram stain) and bacteriological (sputum culture) examination of sputum is recommended; if possible, determination of antibodies to viruses and mycoplasmas. Chest X-ray is performed only for the purpose of differential diagnosis when the development of pneumonia or other lung diseases is suspected. Other additional studies, unless there are serious reasons for it, are usually not undertaken. However, reasons sometimes appear, because A cough can be accompanied by a number of conditions completely different from bronchitis. For example, a cough can occur with a runny nose as a result of discharge (mucus) from the nasopharynx flowing down the back wall of the throat. A dry, painful cough can develop when taking certain medications (captopril, enalapril, etc.). Cough often accompanies chronic reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)). Cough often accompanies asthma. Differential diagnosis In acute cough, the most important differential diagnosis is between OB and pneumonia, as well as between OB and acute sinusitis. In case of chronic cough, the differential diagnosis is carried out taking into account the history of asthma, GERD, postnasal drip, chronic sinusitis and cough associated with taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), etc. Possible causes of prolonged cough • Causes associated with respiratory diseases. Differential diagnosis is carried out using clinical, functional, laboratory, endoscopic and radiation diagnostic methods: • BA; • Chronical bronchitis; • COPD; • chronic infectious lung diseases; • tuberculosis; • sinusitis; • postnasal drip syndrome (nasal mucus flowing down the back wall of the pharynx into the respiratory tract). The diagnosis of postnasal drip may be suspected in patients who describe the sensation of mucus flowing into the throat from the nasal passages or a frequent need to “clear” the throat by coughing. In most patients, nasal discharge is mucous or mucopurulent. With the allergic nature of postnasal drip, eosinophils are usually found in nasal secretions. The causes of postnasal drip can be general cooling of the body, allergic and vasomotor rhinitis, sinusitis, irritating environmental factors and drugs (for example, ACE inhibitors); • sarcoidosis; • lung cancer; • pleurisy. Causes associated with heart disease and arterial hypertension: • taking ACE inhibitors (an alternative is to select another ACE inhibitor or switch to angiotensin II antagonists); • β-blockers (even selective), especially in patients with atopy or hyperreactivity of the bronchial tree; • heart failure (cough at night). Chest radiography and echocardiography help in the differential diagnosis. Causes associated with connective tissue diseases: • fibrosing alveolitis, sometimes in combination with rheumatoid arthritis or scleroderma. A high-resolution computed tomography scan, a study of pulmonary function with determination of the functional residual capacity of the lungs, diffusion capacity of the lungs and restrictive changes are required; • influence of drugs (drugs taken for rheumatoid arthritis, gold drugs, sulfasalazine, methotrexate). Causes associated with smoking: • OB with a prolonged course (more than 3 weeks) or chronic bronchitis; • special caution in relation to smokers over 50 years of age, especially with hemoptysis. In this category of patients, it is necessary to exclude lung cancer. Causes associated with occupational diseases: • asbestosis (workers at construction sites, as well as people working in small auto repair shops). Radiation diagnostics and spirometry, consultation with an occupational pathologist are necessary; • “farmer's lung”. Can be detected in agricultural workers (hypersensitivity pneumonitis caused by exposure to moldy hay), possible asthma; • occupational asthma, starting with a cough, can develop in representatives of various professions associated with exposure to chemical agents, organic solvents in car repair shops, dry cleaners, plastic production, dental laboratories, dental offices, etc. Causes associated with atopy, allergies or hypersensitivity to acetylsalicylic acid: • the most likely diagnosis is asthma. The most common symptoms are transient shortness of breath and mucous sputum. To carry out differential diagnosis, it is necessary to perform the following studies: measuring peak expiratory flow at home; spirometry with bronchodilation test; if possible, determine the hyperreactivity of the bronchial tree (provocation with inhaled histamine or methacholine hydrochloride); assessment of the effect of inhaled glucocorticoids. In the presence of prolonged cough and fever, accompanied by the release of purulent sputum (or without it), it is necessary to exclude: • pulmonary tuberculosis; • eosinophilic pneumonia; • development of vasculitis (for example, periarteritis nodosa, Wegener's granulomatosis). A chest X-ray or computed tomography scan, sputum examination for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, sputum smear and culture, blood test, and determination of C-reactive protein in the blood serum are required. Other causes of prolonged cough: • sarcoidosis (chest x-ray or computed tomography to exclude hyperplasia of the lymph nodes of the respiratory system, infiltrates in the lung parenchyma, morphological examination of biopsy samples of various organs and systems); • taking nitrofurans; • pleurisy (it is necessary to establish the main diagnosis, perform a puncture and biopsy of the pleura, and study the pleural fluid); • GERD is one of the common causes of chronic cough, occurring in 40% of coughing people [7]. Many of these patients complain of reflux symptoms (heartburn or sour taste in the mouth). Often, people whose cough is caused by gastroesophageal reflux do not indicate symptoms of reflux. Indications for consultation with a specialist The indication for consultation with specialists is the persistence of cough during standard empirical therapy for OB. Consultations are necessary: • pulmonologist – to exclude chronic lung pathology; • gastroenterologist – to exclude gastroesophageal reflux; • ENT doctor – to exclude ENT pathology as the cause of cough. Sinusitis, asthma and gastroesophageal reflux can cause prolonged cough (more than 3 weeks) in more than 85% of patients with a normal chest x-ray [7]. Acute bronchitis and pneumonia Early differential diagnosis of OB and pneumonia is fundamentally important, since the timeliness of prescribing appropriate therapy depends on the diagnosis (for OB, as a rule, antiviral and symptomatic; for pneumonia, antibacterial). When making a differential diagnosis between OB and pneumonia, the standard laboratory test is a clinical blood test. According to the results of a recently published systematic review, an increase in the number of leukocytes in peripheral blood to 10.4 × 109/L or more is associated with a 3.7-fold increase in the likelihood of pneumonia, while the absence of this laboratory sign reduces the likelihood of pneumonia by 2-fold. Of even greater value is the content of serum C-reactive protein, the concentration of which above 150 mg/l reliably indicates pneumonia. Table 3 shows the symptoms in patients with cough and their diagnostic significance for pneumonia. Of 9–10 patients with cough and purulent sputum (within 1–3 weeks), pneumonia is diagnosed in 1 patient. A prolonged cough that appears for the first time in a patient causes considerable difficulties for the doctor in the differential diagnosis between OB and BA. In cases where asthma is the cause of cough, patients usually experience episodes of wheezing. Regardless of the presence or absence of wheezing in patients with asthma, a study of pulmonary function reveals reversible bronchial obstruction in tests with b2-agonists or methacholine. It must be borne in mind that in 33% of cases tests with b2-agonists and in 22% of cases with methacholine can be false positive [8]. If false-positive functional testing results are suspected, a trial of therapy for 1–3 weeks is recommended. inhaled glucocorticosteroids (GCS) – in the presence of BA, the cough should stop or its intensity should significantly decrease, which requires further study [9]. Differential diagnosis of OB with the most likely diseases in which cough is present is shown in Table 4. Treatment The main goals of treatment of OB [1, 2]: • alleviating the severity of cough; • reducing its duration; • return of the patient to work. Hospitalization of patients with OB is not indicated. Non-drug treatment [10]: 1. Regime. 2. Facilitate sputum production: • instruct the patient to maintain adequate hydration; • about the benefits of humidified air (especially in dry, hot weather and in winter in any weather); • pay attention to the need to eliminate the patient's exposure to environmental factors that cause coughing (level of evidence C). Drug treatment: • Medicines that suppress cough (dextromethorphan) are prescribed only for debilitating cough; • bronchodilators for debilitating cough (level of evidence A). 3 randomized controlled studies show the effectiveness of bronchodilative therapy in 50% of patients about [7]; • A fixed combination of active substances: salbutamol, hevifenesin and bromhexin (ASCRILI®); • Antibacterial therapy is not indicated for an uncomplicated course of [11]. It is believed that one of the reasons for the abuse of antibiotics [11]. Thanks to the unique combination of broncholitics, mucolics and mukokinetics with a different mechanism for the action of individual attention in the treatment of patients, the use of ASCOLIL® as a symptomatic agent of the drug. Data of controlled studies and materials of the analytical review of Coranov’s cooperation indicate the effectiveness of a fixed combination of active substances - salbutamol, hevifenesin and bromhexin, which make up ASCOLIL® - in the treatment of patients with symptoms of impaired mucoregoing processes, as well as polyfunctionality and safety of the drug [13–15] . The pharmacological properties of the main (active) drugs that are part of Askoril® are quite known. Salbutamol is a selective short -acting β2 - agonist with broncholitic and mucolytic effects. When administering the bioavailability of salbutamol is 50%, the meal reduces the rate of absorption of the drug, but does not affect its bioavailability. Gweapheninos enhances the secretion of the liquid part of bronchial mucus, reduces the surface tension and adhesive properties of sputum and thereby increases its volume, activates the cyliar apparatus of the bronchi, facilitates the removal of sputum and promotes the transition of unproductive cough to productive. Bromhexine - a classic mucolytic drug, is a derivative of the alkaloid Vasitsin. The mucolytic effect is associated with the depolymerization of mucoprotein and mucopolysaccharide fibers. The drug stimulates the synthesis of neutral polysaccharides and the release of lysosomal enzymes, increases the serous component of the bronchial secret, activates the cilia of the ciliated epithelium, reduces the viscosity of sputum, increases its volume and improves the departure. One of the unique properties of bromhexine is the stimulation of the synthesis of endogenous surfacttant. Menthol is another component of ASCOLIL®, contains essential oils that have a soothing, soft antispasmodic and antiseptic effect. According to N.M. Shmeleva and E.I. Shmeleva, the appointment of drugs Askil® in patients about a protracted course leads to reduction of symptoms of the disease, improve the general condition and prevent secondary bacterial complications [16]. The clinical efficiency of Ascoril® compared to double combinations of salbutamol and hevyaphenesin or salbutamol and bromhexine is shown in a comparative study with the participation of 426 patients with a productive cough in acute and chronic bronchitis and amounted to 44, 14 and 13%, respectively [17]. Touching upon the use of antibiotics for the treatment of patients about, the following should be noted. In a randomized study, 46 patients were divided into 4 groups: patients of the 1st group received inhalations of salbutamol and placebo in capsules; Patients of the 2nd group were prescribed inhalations of salbutamol and erythromycin inside; The 3rd group received erythromycin and placebo inhalation; Patients of the 4th group were prescribed placebo in capsules and placebo inhalation. The cough disappeared in a larger number of patients who received salbutamol, compared with patients who received erythromycin or placebo (39 and 9%, respectively, p = 0.02). Patients treated by Salbutamol were able to start work earlier (p = 0.05) [8]. When comparing the effectiveness of miclitromycin and salbutamol, 42 patients obtained the following results: after 7 days, the cough disappeared in 59% of patients in the group of Salbutamol and in 12% of patients in the group received erythromycin (p = 0.002). In smoking patients, the complete disappearance of cough was noted in 55% of cases in a group of patients who were prescribed inhalations of salbutamol; In a group of patients treated with erythromycin, he did not completely disappear in anyone (p = 0.03). Antibacterial therapy is indicated for obvious signs of bacterial lesions of the bronchi (purulent sputum, elevated body temperature, signs of intoxication of the body) [1, 12]. With bacterial etiology, one of the listed antibacterial drugs is recommended in general -metal doses: amoxicillin or macrolides of the II generation with improved pharmacokinetic properties (clarithromycin, azithromycin). Prevention of acute bronchitis based on the mainly viral etiology of about, the prevention of the disease is primarily in the prevention of SARS. Attention should be paid to compliance with personal hygiene rules: frequent hand washing; Minimization of the contacts “Eyes - Hands”, “Nose - Hands”. Most viruses are transmitted in this way in such a contact. Special studies of the effectiveness of this preventive measure in day hospitals for children and adults showed its high efficiency [18, 19]. An annual antifungal prevention reduces the frequency of occurrence (level of evidence a). Indications for annual influenza vaccination: • age over 50 years; • chronic diseases regardless of age; • being in closed groups; • prolonged therapy with acetylsalicylic acid in childhood and adolescence; • II and III trimesters of pregnancy in the epidemic period of influenza. In middle -aged persons, vaccination reduces the number of flu episodes and disability in this regard [20]. Vaccination of medical personnel leads to a decrease in mortality among elderly patients [21]. In elderly weakened patients, vaccination reduces mortality by 50%, the hospitalization frequency is 40% [22]. Indications for drug prophylaxis: in the proven epidemic period, non -impunested persons with a high risk of influenza is recommended inhalation of a bunning 10 mg/day [5] or a landscape of 75 mg/day orally [23]. Antiviral prevention is effective in 70–90% of people [5]. In case of an uncomplicated prognosis, favorable, with a complicated course of the disease, depends on the nature of the complications and may relate to a different category of diseases.

Literature 1. Pulmonology. National leadership. Brief edition / Ed. A.G. Chuchalina. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2013. 2. Falsey AR, Griddle MM, Kolassa JE et al. Evaluation of a handwashing intervention to reduce respiratory illness rates in senior day-care centers // Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1999. Vol. 20. R. 200–202. 3. Irwin RS, Curly FJ, French CI Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy // Am. Rev. Respira. Dis. 1999. Vol. 141. R. 640–647. 4. Govaert TM, Sprenger MJ, Dinant GJ et al. Immune response to influenza vaccination of elderly people. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial // Vaccine. 1994. Vol. 12. R. 1185–1189. 5. Govaert TM, Thijs CT, Masurel N. et al. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial // JAMA. 1994. Vol. 272. R. 1661–1665. 6. Monto AS Zanamivir in the prevention of influenza among healthy adults: a randomized controlled trial // JAMA. 1999. Vol. 282. R. 31–35. 7. Lambert J., Mobassaleh M., Grand RJ Efficacy of cimetidine for gastric acid suppression in pediatric patients // J. Pediatr. 1999. Vol. 120.R. 474–478. 8. Smucny JJ Are beta-2-agonists effective treatments for acute bronchitis or acute cough in patients without underlying pulmonary disease? // J. Farm. Pract. 2001. Vol. 50. R. 945–951. 9. Quackenboss JJ, Lebowitz MD, Kryzanowski M. The normal range of diurnal changes in peak expiratory flow rates. Relationship to symptoms and respiratory disease // Am. Rev. Respira. Dis. 1999. Vol. 143. R. 323–330. 10. Nakagawa NK, Macchione M, Petrolino HM et al. Effects of a heat and moisture exchange and a heated humidifier on respiratory mucus in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation // Crit. Care Med. 2000. Vol. 28. R. 312–317. 11. Gonzales R., Steiner JF, Lum A., Barrett PH Deccreasing antibiotic use in ambulatory practice: impact of a multidimensional intervention on the treatment of uncomplicated acute bronchitis in adults // JAMA. 1999. Vol. 281. R. 1512. 12. Canadian guidelines for the management of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis // Can. Resp. J. 2003. Suppl. R. 3–32. 13. Fedoseev G.B., Zinakova M.K., Rovkina E.I. Clinical aspects of the use of Ascoril in a pulmonology clinic // New St. Petersburg Medical Gazette. 2002. No. 2. P. 64–67. 14. Ainapure SS, Desai A., Korde K. Efficacy and safety of Ascoril in the management of cough - National Study Group report // J. Indian. Med. Assoc. 2001. Vol. 99. R. 111–114. 15. Prabhu Shankar S., Chandrashekharan S., Bolmall CS, Baliga V. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of salbutamol+guaiphenesin+bromhexine (Ascoril) expectorant versus expectorants containing salbutamol and either guaiphenesin or bromhexine in productive cough: a randomized controlled comparative study // J. Indian. Med. Assoc. 2010. Vol. 108. R. 313–320. 16. Shmeleva N.M., Shmelev E.I. Modern aspects of mucoactive therapy in pulmonological practice // Ter. archive. 2013. No. 3. R. 107–109. 17. Prabhu Shankar S., Chandrashekharan S., Bolmall CS, Baliga V. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of salbutamol + guaiphenesin + bromhexine (Ascoril) expectorant versus expectorants containing salbutamol and either guaiphenesin or bromhexine in productive cough: a ran– domised controlled comparative study // J. Indian. Med. Assoc. 2010. Vol. 108. R. 313–314, 316–318, 320. 18. Uhari M., Mottonen M. An open randomized controlled trial of infection prevention in child day-care centers // Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1999. Vol. 18. R. 672–677. 19. Roberts L., Jorm L. Effect of infection control measures on the frequency of diarrhea episodes in child care: a randomized, controlled trial // Pediatrics. 2000. Vol. 105. R. 743–746. 20. Bridges CB, Thompson WW, Meltzer M. et al. Effectiveness and cost-benefit of influenza vaccination of healthy working adults: A randomized controlled trial // JAMA. 2000. Vol. 284. R. 1655–1663. 21. Carman WF, Elder AG, Wallace LA et al. Effects of influenza vaccination of health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: a randomized controlled trial // Lancet. 2000. Vol. 355. R. 93–97. 22. Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J., von Sternberg T. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community // N. Engl. J. Med. 1994. Vol. 331. R. 778–784. 23. Hayden FG Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza // N. Engl. J. Med. 1999. Vol. 341. R. 1336–1343.

Treatment of acute obstructive bronchitis

In pediatrics, diagnosis and treatment of the disease are carried out on the basis of the clinical recommendations “Acute obstructive bronchitis in children”. The sick child is prescribed semi-bed rest. The room should be regularly wet cleaned and ventilated. Food should be easily digestible and served warm. Be sure to drink plenty of warm drinks, which helps thin the mucus and make it easier to cough up.

An important element in the treatment of bronchitis is drinking plenty of fluids.

Drug therapy for obstructive bronchial inflammation is carried out only as prescribed by a doctor and may include:

- antiviral drugs (ribavirin, interferon);

- antispasmodics (drotaverine, papaverine);

- mucolytics (ambroxol, acetylcysteine);

- bronchodilator inhalers (fenoterol hydrobromide, orciprenaline, salbutamol).

Antibiotics are prescribed only when a secondary bacterial infection occurs. The most commonly used drugs are cephalosporins, beta-lactams, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides.

In order to improve mucus discharge, vibration, percussion or general back massage is performed, and breathing exercises are recommended.

Prognosis and prevention

The prognosis is favorable. With adequate treatment, the disease ends in recovery within 7–21 days. If the body is highly allergenic, bronchitis can take a recurrent or chronic course and over time transform into asthmatic, and then into bronchial asthma.

The disease begins acutely and is characterized by the development of bronchial obstruction and infectious toxicosis.

Prevention is based on carrying out activities aimed at increasing the overall defenses of the body (proper nutrition, exercise, walks in the fresh air, giving up bad habits).

Bronchitis

In the case of bronchitis with a severe concomitant form of ARVI, treatment is indicated in the pulmonology department; in case of uncomplicated bronchitis, treatment is outpatient. Therapy for bronchitis should be comprehensive: fighting infection, restoring bronchial patency, eliminating harmful provoking factors. It is important to complete the full course of treatment for acute bronchitis to prevent it from becoming chronic. In the first days of the disease, bed rest, drinking plenty of fluids (1.5 - 2 times more than normal), and a dairy-vegetable diet are indicated. During treatment, smoking cessation is required. It is necessary to increase the air humidity in the room where a patient with bronchitis is located, since the cough intensifies in dry air.

Therapy for acute bronchitis may include antiviral drugs: interferon (intranasal), for influenza - rimantadine, ribavirin, for adenoviral infection - RNase. In most cases, antibiotics are not used, except in cases of bacterial infection, in the case of prolonged acute bronchitis, or in cases of a pronounced inflammatory reaction according to the results of laboratory tests. To improve the removal of sputum, mucolytic and expectorant agents are prescribed (bromhexine, ambroxol, expectorant herbal tea, inhalations with soda and saline solutions). In the treatment of bronchitis, vibration massage, therapeutic exercises, and physiotherapy are used. For a dry, unproductive, painful cough, the doctor may prescribe medications that suppress the cough reflex - oxeladine, prenoxdiazine, etc.

Chronic bronchitis requires long-term treatment, both during exacerbation and during remission. In case of exacerbation of bronchitis, with purulent sputum, antibiotics are prescribed (after determining the sensitivity of the isolated microflora to them), sputum thinners and expectorants. In the case of the allergic nature of chronic bronchitis, it is necessary to take antihistamines. The regime is semi-bed, be sure to drink plenty of warm water (alkaline mineral water, tea with raspberries, honey). Sometimes therapeutic bronchoscopy is performed, with washing of the bronchi with various medicinal solutions (bronchial lavage). Breathing exercises and physiotherapy (inhalations, UHF, electrophoresis) are indicated. At home, you can use mustard plasters, medical cups, and warm compresses. To strengthen the body's resistance, vitamins and immunostimulants are taken. Outside of exacerbation of bronchitis, sanatorium-resort treatment is desirable. Walking in the fresh air is very useful, normalizing respiratory function, sleep and general condition. If there are no exacerbations of chronic bronchitis within 2 years, the patient is removed from dispensary observation by a pulmonologist.