Attention!

The information in the article is for reference only and cannot be used for self-diagnosis or self-medication. To decipher the test results, contact a specialist.

There is no such person who has never suffered from bronchitis in his life. It affects people of any age. In adults, if bronchitis develops, it is mild and does not have any health consequences.

Severe obstructive bronchitis most often affects children. The younger the child, the more complex the disease. It is less treatable. Sometimes it takes on a rapid course that threatens the baby’s life.

Obstructive bronchitis, what is it?

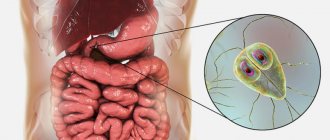

Obstructive bronchitis is classified as an inflammatory lesion of the bronchial tree. It affects the mucous membrane lining the inside of the bronchi. Edema narrows the lumen of these structures. Inflammation during bronchitis spreads throughout the entire thickness of the bronchial wall. The function of the ciliary epithelium is impaired.

The disease occurs with symptoms of obstruction, which are expressed in impaired bronchial patency. In children, obstructive bronchitis occurs with attacks of unproductive cough, which is accompanied by noisy whistling breathing.

Such patients are characterized by forced expiration, rapid breathing and distant wheezing. Obstructive bronchitis in children develops at any age. More often than other age groups, it affects children aged six months to 5 years.

The disease is more often registered in children with allergies, weakened immunity and the presence of a genetic predisposition, frequent and prolonged viral respiratory infections. The number of cases of obstructive bronchitis in children is steadily increasing.

Therapy of acute obstructive syndrome in children with acute respiratory diseases

Despite modern advances in medicine, in the 21st century the prevalence of infections not only does not decrease, but is increasingly increasing. For a long time, the first place in the structure of infectious morbidity in children is occupied by acute respiratory diseases (ARI) [1, 2]. According to the state report of Rospotrebnadzor, in Russia the incidence of acute respiratory infections in children in 2012 was more than 28 million (28,423,135), or 19,896.3 cases per 100 thousand children [3]. Such a high prevalence of acute respiratory infections in childhood is due to both the contagiousness of the infectious factor and the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the child’s body. A significant place in the etiological structure of acute respiratory infections is given to viral infections. Over the past decades, new viruses have been identified that determine the severe course of acute respiratory infections with airway obstruction, especially in children in the first years of life. Particular attention is paid to the role of metapneumovirus, coronovirus, bocavirus, rhinovirus, influenza virus reassortants, and respiratory syncytial virus in the development of obstructive airway syndrome. Their role in the development of acute obstructive airway syndrome (AOOS) in children is undeniable; at the same time, there is evidence indicating their possible role in the development of bronchial asthma (BA) in genetically predisposed individuals [1, 4].

Acute obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract in children are quite common and sometimes severe, accompanied by signs of respiratory failure. The most common of them is acute stenosing laryngotracheitis (croup), caused by inflammation of the mucous and submucosal space of the larynx and trachea, involving the tissues and structures of the subglottic space in the process and the development of laryngeal stenosis. Also quite often the cause of acute obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract against the background of acute respiratory viral infection (ARVI) in children are acute obstructive bronchitis, bronchiolitis and asthma [5].

The term “croup” refers to a clinical syndrome accompanied by a hoarse or hoarse voice, a rough “barking” cough and difficulty (stenotic) breathing. In the domestic literature, this disease is described under the name “stenosing laryngotracheitis”, in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) - “acute obstructive laryngitis”. However, in practical work, the most widely used term is “croup”, which is recommended by leading pediatric infectious disease specialists to be used as a general terminology.

Broncho-obstructive syndrome is a symptom complex of functional or organic origin, the clinical manifestations of which consist of prolonged exhalation, whistling, noisy breathing, attacks of suffocation, coughing, etc. The terms “broncho-obstructive syndrome” and “croup” cannot be used as an independent diagnosis.

The prevalence of obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract due to acute respiratory viral infections is quite high, especially in children in the first 6 years of life. This is due to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the respiratory tract in young children. Thus, the frequency of development of bronchial obstruction against the background of acute respiratory diseases in children of the first years of life is, according to various authors, from 5% to 50%. Most often, obstructive conditions are observed in children with a family history of allergies. The same trend exists in children, who often suffer from respiratory infections more than 6 times a year. In Western literature, the term “wheezing” is currently accepted - “noisy breathing” syndrome, combining laryngotracheal causes of OSDP and broncho-obstructive syndrome. It has been noted that 50% of children experience wheezing and shortness of breath at least once in their lives, and recurrent bronchial obstruction is typical for 25% of children [2, 6, 7].

Our analysis of the prevalence of obstructive syndrome in children with acute respiratory infections, which is the reason for hospitalization in the respiratory infections department of the St. Vladimir Children's City Clinical Hospital in Moscow, indicates an increase in patients with obstructive respiratory tract syndrome in recent years. According to our data, in 2011, 1348 children were admitted to the respiratory department, of which 408 children had a fairly severe course of OSDP due to acute respiratory infections. In subsequent years, we observed an increase in the role of NSDP, which determines the severity of acute respiratory infections; for example, in 2012, the number of hospitalizations reached 1636, and children with NSDP increased to 669. It should be noted that in 90% of cases, the age of children with NSDP was less than 5 years. An analysis was carried out of the reasons for the lack of effectiveness of treatment for obstructive conditions in children at the prehospital stage. It has been established that the main ones are inadequate assessment of the severity of NSDP and, accordingly, the lack of timely and rational therapy for NSDP, late prescription of anti-inflammatory therapy, and lack of control over the inhalation technique.

The high incidence of OSDP in children is due to both the characteristics of the infectious factor in the modern world and the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the child’s body. It is known that the immune system of children in the first years of life is characterized by immaturity and insufficient reserve capabilities. Thus, the response of the innate immune system of children in the first years of life is characterized by limited secretion of interferons (IFN), insufficient complement activity, and decreased cellular cytotoxicity. The features of adaptive immunity in this age group of patients are due to the Th2 direction of the immune response, which often contributes to the development of allergic reactions, the immaturity of the humoral part of the immune response with a decrease in the level of secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A on the mucous membranes, and the predominant production of IgM to infectious pathogens. The immaturity of the immune response contributes to frequent acute respiratory infections and often determines the severity of their course [1].

Often the development of OSDP in children of the first years of life is due to the anatomical and physiological features of the structure of the respiratory tract of this age group of patients. Among them, especially important are the presence of hyperplasia of glandular tissue, secretion of predominantly viscous sputum, relative narrowness of the respiratory tract, smaller volume of smooth muscles, low collateral ventilation, and structural features of the larynx. The development of croup in children with ARVI is due to the small absolute size of the larynx, the softness of the cartilaginous skeleton, and the loose and elongated epiglottis. All this creates special preconditions for the components of stenosis: spasm and edema. In addition, due to the fact that the plates of the thyroid cartilage in children converge at a right angle (in adults it is sharp), the vocal cords (folds) become disproportionately short, and up to 7 years the depth of the larynx exceeds its width. The smaller the child, the greater the relative area occupied by loose connective tissue in the subglottic space, which increases the volume of swelling of the laryngeal mucosa. In children of the first three years of life, the larynx, trachea and bronchi have a relatively smaller diameter than in adults. The narrowness of all parts of the breathing apparatus significantly increases aerodynamic resistance. Young children are characterized by insufficient rigidity of the bone structure of the chest, which freely reacts by retracting compliant places to increase resistance in the airways, as well as features of the position and structure of the diaphragm. The differentiation of the nervous apparatus is also insufficient due to the fact that the 1st and 2nd reflexogenic zones are fused along their entire length and the 3rd reflexogenic zone, the receptors of which are abundantly branched throughout the mucous membrane of the subglottic space, is not formed, which contributes to the occurrence of prolonged spasm of the glottis and laryngeal stenosis. It is these features that contribute to the frequent development and recurrence of airway obstruction in children of the first years of life, especially against the background of acute respiratory infections [1, 5, 8].

The prognosis for the course of OSDP can be quite serious and depends on the form of the disease that caused the development of obstruction, and the timely implementation of pathogenetically determined treatment and prevention regimens.

The main directions of therapy for OSDP in children are the actual treatment of respiratory infection and treatment of airway obstruction.

According to modern data, the main place in the mechanism of development of OODP is attributed to inflammation. The development of inflammation of the mucous membrane of the upper and lower respiratory tract contributes to hypersecretion of viscous mucus, the formation of edema of the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract, disruption of mucociliary transport and the development of obstruction. Accordingly, the main directions of therapy for OSDP are anti-inflammatory therapy [9–11].

Inflammation is an important factor in bronchial obstruction in young children and can be caused by various factors. As a result of their influence, a cascade of immunological reactions is triggered, promoting the release of type 1 and type 2 mediators into the peripheral bloodstream. It is with these mediators (histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins) that the main pathogenetic mechanisms of obstructive syndrome are associated - increased vascular permeability, the appearance of edema of the bronchial mucosa, hypersecretion of viscous mucus, and the development of bronchospasm.

In children of the first years of life, it is edema and hyperplasia of the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract that is the main cause of airway obstruction at different levels. The developed lymphatic and circulatory systems of the child’s respiratory tract provide him with many physiological functions. However, under pathological conditions, edema is characterized by thickening of all layers of the bronchial wall (submucosal and mucous layers, basement membrane), which leads to impaired airway patency. With recurrent bronchopulmonary diseases, the structure of the epithelium is disrupted, its hyperplasia and squamous metaplasia are noted.

Another equally important mechanism of OSDP in children of the first years of life is a violation of bronchial secretion, which develops with any adverse effect on the respiratory system and in most cases is accompanied by an increase in the amount of secretion and an increase in its viscosity. The function of the mucous and serous glands is regulated by the parasympathetic nervous system; acetylcholine stimulates their activity. This reaction is initially defensive in nature. However, stagnation of bronchial contents leads to disruption of the ventilation and respiratory function of the lungs. The thick and viscous secretion produced, in addition to inhibiting ciliary activity, can cause bronchial obstruction due to the accumulation of mucus in the respiratory tract. In severe cases, ventilation disorders are accompanied by the development of atelectasis.

A significant role in the development of broncho-obstructive syndrome (BOS) is played by bronchial hyperreactivity. Bronchial hyperreactivity is an increase in the sensitivity and reactivity of the bronchi to specific and nonspecific stimuli. The cause of bronchial hyperreactivity is an imbalance between excitatory (cholinergic, noncholinergic and α-adrenergic systems) and inhibitory (β-adrenergic system) influences on bronchial tone. It is known that stimulation of β2-adrenergic receptors by catecholamines, as well as increasing the concentration of cAMP and prostaglandins E2, reduces the manifestations of bronchospasm. According to the classical theory of A. Szentivanyi (1968), patients with bronchial hyperreactivity have a defect in the biochemical structure of β2 receptors, which is reduced to adenylate cyclase deficiency. These patients have a reduced number of β-receptors on lymphocytes, there is an imbalance of adrenergic receptors towards hypersensitivity of α-adrenergic receptors, which predisposes to smooth muscle spasm, mucosal edema, infiltration and hypersecretion. Hereditary blockade of adenylate cyclase reduces the sensitivity of β2-adrenergic receptors to adrenergic agonists, which is quite common in patients with asthma. At the same time, some researchers point to the functional immaturity of β2-adrenergic receptors in children in the first months of life.

It has been established that in young children, M-cholinergic receptors are quite well developed, which, on the one hand, determines the characteristics of the course of broncho-obstructive diseases in this group of patients (tendency to develop obstruction, production of very viscous bronchial secretions), on the other hand, explains the pronounced bronchodilator effect They have M-anticholinergics.

Thus, the anatomical and physiological characteristics of young children determine both the high prevalence of OSDP in children of the first years of life and the mechanisms of its development with the corresponding clinical picture of “wet asthma”.

Therapy for OSDP should be started immediately after symptoms are identified at the patient's bedside. It is necessary to immediately begin emergency therapy and at the same time find out the causes of bronchial obstruction.

The main directions of emergency treatment of OSDP include measures for bronchodilator, anti-inflammatory therapy, improvement of bronchial drainage function and restoration of adequate mucociliary clearance. A severe attack of bronchial obstruction requires oxygenation of inhaled air, and sometimes artificial ventilation.

Emergency treatment of OSDP in children should be carried out taking into account the pathogenesis of obstruction in different age periods. In the genesis of BOS in young children, inflammatory edema and hypersecretion of viscous mucus predominate, and bronchospasm is slightly expressed. With age, bronchial hyperreactivity increases and along with this the role of bronchospasm increases.

The main directions of treatment for acute obstructive conditions of the upper and lower respiratory tract in children with acute respiratory infections are the treatment of the respiratory infection itself and the treatment of airway obstruction [12]. Of course, treatment of acute respiratory infections should be comprehensive and individual in each specific case.

Etiotropic therapy for the most common viral infections is currently difficult due to the narrow spectrum of action of antiviral drugs, the age limit for their use in children in the first years of life, and the insufficient evidence base for the effectiveness of this group of drugs. Currently, recombinant interferon preparations and drugs that stimulate the synthesis of endogenous interferon are actively used in the treatment of acute respiratory infections of viral etiology. The prescription of antibacterial drugs is indicated in the case of prolonged fever (more than 3-4 days), and/or the presence of signs of respiratory failure in the absence of biofeedback, and/or suspected pneumonia, and/or pronounced changes in the clinical blood test.

Modern standards for the treatment of obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract are defined in international and national program documents [5, 9, 13], according to which the main drugs in the treatment of OSDP are bronchodilators and drugs with anti-inflammatory effects. The widespread use of inhaled glucocorticosteroids (ICS) is recommended as an effective anti-inflammatory therapy. ICS are the most effective treatment for acute stenosing laryngotracheitis, bronchial asthma and acute obstructive bronchitis. The mechanism of their therapeutic action is associated with a powerful anti-inflammatory effect. The anti-inflammatory effect of ICS is associated with an inhibitory effect on inflammatory cells and their mediators, including the production of cytokines (interleukins), pro-inflammatory mediators and their interaction with target cells. ICS have an effect on all phases of inflammation, regardless of its nature, and the key cellular target may be epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. ICS directly or indirectly regulate the transcription of target cell genes. They increase the synthesis of anti-inflammatory proteins (lipocortin-1) or reduce the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines - interleukins, tumor necrosis factor, etc. With long-term therapy with ICS in patients with bronchial asthma, the number of mast cells and eosinophils on the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract is significantly reduced, cell membranes are stabilized, membranes of lysosomes and vascular permeability decreases.

In addition to reducing inflammatory swelling of the mucous membrane and bronchial hyperreactivity, ICS improve the function of β2-adrenergic receptors both by synthesizing new receptors and increasing their sensitivity. Therefore, ICS potentiate the effects of β2-agonists.

Inhaled use of GCS creates high concentrations of drugs in the respiratory tract, which ensures the most pronounced local anti-inflammatory effect and minimal manifestations of systemic (undesirable) effects.

However, the effectiveness and safety of ICS in the treatment of OSDP in children is largely determined by the method of delivery directly to the respiratory tract and the inhalation technique [14, 16]. Delivery systems currently available include metered dose aerosol inhalers (MDIs), MDIs with a spacer and face mask (Aerochamber, Babyhaler), breath-activated MDIs, powder inhalers and nebulizers. It is now recognized that the optimal system for delivering drugs to the respiratory tract for acute respiratory depression in young children is a nebulizer. Its use contributes to the best positive dynamics of clinical data, a sufficient bronchodilator effect of the peripheral sections of the bronchi, and the technique of its use is almost error-free. The main goal of nebulizer therapy is to deliver a therapeutic dose of the desired drug in aerosol form in a short period of time, usually 5–10 minutes. Its advantages include: an easily performed inhalation technique, the ability to deliver a higher dose of the inhaled substance and ensure its penetration into poorly ventilated areas of the bronchi. In young children, it is necessary to use a mask of the appropriate size; from 3–4 years of age, it is better to use a mouthpiece than a mask, since the use of a mask reduces the dose of the inhaled substance due to its sedimentation in the nasopharynx.

Currently, the following ICS can be used in the practice of a doctor: beclomethasone, budesonide, fluticasone propionate, mometasone furoate and ciclesonide. It is necessary to note the age-related aspects of prescribing ICS in children. Thus, in children from 6 months of age, the drug budesonide suspension is approved for use in inhalation through a compressor nebulizer, from 12 months - fluticasone propionate through a spacer, beclomethasone propionate is approved for use in pediatric practice from 4 years, ciclesonide from 6 years, and mometasone furoate from the age of 12.

To carry out nebulizer therapy, only drug solutions specially designed for these purposes are used, approved by the Pharmacological Committee of the Russian Federation for nebulizers. At the same time, even a small particle of a solution in an aerosol retains all the medicinal properties of the substance; the solutions themselves for nebulizer therapy do not cause damage to the mucous membrane of the bronchi and alveoli, and packaging in the form of bottles or nebulas allows for convenient dosing of drugs both in hospital and at home.

More recently, a whole line of drugs intended for nebulizer therapy was registered in our country, including ICS - budesonide (Budenit Steri-Neb) and 3 bronchodilators: salbutamol (Salamol Steri-Neb), ipratropium bromide (Ipratropium Steri-Neb) and the combination salbutamol/ ipratropium bromide (Ipramol Steri-Neb).

The drug Budenit Steri-Neb (budesonide) is a generic version of the original drug budesonide Pulmicort suspension. According to the definition of the Food and Drugs Administration of the United States (FDA), a generic drug is a drug comparable to the original drug in dosage form, strength, route of administration, quality, pharmacological properties and indications for use. Generic drugs that meet this definition are characterized by: compliance with pharmacopoeial requirements, production under GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) conditions, almost complete compliance with the original product in composition (excipients may be different) and effects produced, lack of patent protection , a more affordable price than the original drug.

All of the above characteristics can be attributed to Steri-Heaven. The preparations in nebulas are created using advanced 3-stage “hot sealing” technology, which allows you to achieve maximum sterility. Each Steri-Sky contains one dose of the drug, and the drug is completely ready for use (does not require dilution), which eliminates dosing errors [15]. Steri-Sky plastic ampoules are easy to open. Medicines found in Steri-Sky do not contain benzalkonium chloride and other preservatives, which makes them safer, and this is very important when used, especially in pediatric practice.

Thus, the main principles of treatment of bronchial obstruction are anti-inflammatory treatment and the use of bronchodilators. It is ICS that are an important component of anti-inflammatory therapy for BOS. Currently, nebulized budesonide for exacerbation of asthma is considered as an alternative to systemic glucocorticosteroids [13]. The advantage of budesonide when administered by inhalation is the faster action of GCS (within 1–3 hours), maximum improvement of bronchial patency after 3–6 hours, reduction of bronchial hyperreactivity and a much higher safety profile.

Taking into account the fact that the majority of clinical studies of nebulized budesonide therapy used the original drug Pulmicort (suspension), a comparison of the pharmaceutical equivalence of these drugs was performed to assess the comparability of the results of these studies in relation to Budenitis Steri-Neb.

A direct comparison of the therapeutic efficacy and safety of Budenit Steri-Neb (TEVA, Israel) and Pulmicort (suspension) (AstraZeneca, UK) was conducted in a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled study in a cohort of children (from 5 years to 11 years 8 months) delivered to emergency departments for asthma exacerbation (Phase III parallel group study; 23 study sites recruited patients in 6 countries—Estonia, Israel, Latvia, Poland, Colombia, and Mexico). The study included 302 children. Budenit Steri-Neb (0.5 mg/2 ml and 1 mg/2 ml) and Pulmicort suspension (0.5 mg/2 ml and 1 mg/2 ml) did not differ significantly in component composition, suspension particle size, particle distribution generated aerosol by size, amount of budesonide in the inhaled mixture. Thus, chemical and pharmacological studies of Budenit Steri-Neb and the original drug Pulmicort revealed the equivalence of the budesonide suspension of the two manufacturers in terms of the main indicators affecting the therapeutic effect of ICS. Therapeutic equivalence and similar safety profile of Budenit Steri-Neb and the original drug Pulmicort (suspension) have been demonstrated, which allows extrapolation of data obtained in studies of nebulized budesonide [16].

Thus, according to international and national recommendations, the most optimal, affordable and effective anti-inflammatory drug for the treatment of acute stenosing laryngotracheitis, broncho-obstructive syndrome in children over 6 months of age is a budesonide suspension with inhalation use through a nebulizer. The appearance on the pharmaceutical market of high-quality generics in the form of Steri-Sky, including budesonide (Budenit Steri-Neb), expands the choice of pediatricians in the treatment of acute stenosing laryngotracheitis and broncho-obstructive syndrome in children. Early administration of this drug for OSDP is the key to a favorable prognosis and prevention of complications.

Data from regulatory documents [5, 9, 13] and the results of our own clinical observations indicate that the use of modern ICS is a highly effective and safe method of treating severe OADP. In children from 6 months of age and older, the best is inhalation of budesonide through a nebulizer at a daily dose of 0.25–1 mg/day (the volume of the inhaled solution is adjusted to 2–4 ml by adding saline). The drug can be prescribed once a day, however, as our experience shows, at the height of a severe attack of broncho-obstruction or laryngeal stenosis of 2-3 degrees in children of the first years of life, inhalations of the drug 2 times a day are more effective. In patients who have not previously received ICS, it is advisable to start with a dose of 0.5 mg every 12 hours, and on days 2–3, with a good therapeutic effect, switch to 0.25–0.50 mg once a day. It is advisable to prescribe IGS 15–20 minutes after inhalation of a bronchodilator, but it is also possible to use both drugs simultaneously in the same nebulizer chamber. The duration of therapy with inhaled corticosteroids is determined by the nature of the disease, the duration and severity of the obstruction, as well as the effect of the therapy. In children with acute obstructive bronchitis with severe bronchial obstruction, the need for ICS therapy is usually 5-7 days, and in children with croup - 2-3 days.

Broncholytic therapy

β2-adrenergic agonists, anticholinergic drugs and their combination, as well as short-acting theophyllines can be used as bronchodilator therapy for BOS.

According to national recommendations, short-acting β2-agonists (salbutamol, terbutaline, fenoterol) are the first choice drugs. The effect of this group of drugs begins 5–10 minutes after inhalation and lasts 4–6 hours. A single dose of salbutamol inhaled through a MDI is 100–200 mcg (1–2 doses); when using a nebulizer, the single dose can be significantly increased and is 2.5 mg (nebulas of 2.5 ml of 0.1% solution). The emergency treatment algorithm for severe BOS involves three inhalations of a short-acting β2-agonist over 1 hour with an interval of 20 minutes. Drugs in this group are highly selective and therefore have minimal side effects. However, with long-term uncontrolled use of short-acting β2-agonists, it is possible to increase bronchial hyperreactivity and reduce the sensitivity of β2-adrenergic receptors to the drug.

Anticholinergic drugs (ipratropium bromide) can be used as bronchodilator therapy, taking into account the pathogenetic mechanisms of BOS. This group of drugs block muscarinic M3 receptors for acetylcholine. The bronchodilator effect of the inhaled form of ipratropium bromide develops 15–20 minutes after inhalation. Through a MDI with a spacer, 2 doses (40 mcg) of the drug are inhaled once, through a nebulizer - 8-20 drops (100-250 mcg) 3-4 times a day. Anticholinergic drugs in cases of BOS arising from a respiratory infection are somewhat more effective than short-acting α2-agonists.

It has now been established that a physiological feature of young children is the presence of a relatively small number of adrenergic receptors; with age, there is an increase in their number and an increase in sensitivity to the action of mediators. The sensitivity of M-cholinergic receptors, as a rule, is quite high from the first months of life. These observations served as a prerequisite for the creation of combination drugs. Most often in the complex therapy of biofeedback in young children, a combination drug is currently used that combines 2 mechanisms of action: stimulation of adrenergic receptors and blockade of M-cholinergic receptors. When ipratropium bromide and fenoterol are used together, the bronchodilator effect is achieved by acting on various pharmacological targets [9, 11, 13].

Mucolytic and expectorant therapy

Mucolytic and expectorant therapy for children with OSDP of infectious origin is carried out taking into account the age of the child, the severity of the respiratory infection, the amount of sputum produced and its rheological properties. The main goal is to thin the mucus, reduce its adhesiveness and increase the effectiveness of the cough.

If children have an unproductive cough with viscous sputum, it is advisable to combine the inhalation (via nebulizer) and oral route of administration of mucolytics, the best of which are ambroxol preparations (Lazolvan, Ambrobene, Ambrohexal, etc.). These drugs have proven themselves well in the complex treatment of broncho-obstructive syndrome in children. They have a pronounced mucolytic and mucokinetic effect, a moderate anti-inflammatory effect, increase the synthesis of surfactant, do not increase bronchial obstruction, and practically do not cause allergic reactions. Ambroxol preparations for respiratory infections in children are prescribed 7.5–15 mg 2–3 times a day in the form of syrup, solution and/or inhalation.

For children with an obsessive, unproductive cough and lack of sputum, it is advisable to prescribe expectorant medications: alkaline drinks, herbal remedies, etc. Herbal medicines should be prescribed to children with allergies with caution. We can recommend preparations created from natural plant materials using modern technologies (ivy leaf extract - Prospan, Bronchipret, etc.). A combination of expectorants and mucolytic drugs is possible.

Thus, a feature of the course of acute respiratory infections in children in the first years of life is the frequent development of acute obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract. The main causes of acute obstructive conditions of the respiratory tract in children with ARVI are acute stenosing laryngotracheitis, acute obstructive bronchitis, bronchiolitis and bronchial asthma. These conditions require urgent treatment. The main method of drug delivery during an exacerbation of the disease is inhalation using nebulizers. The main directions of therapy for OSDP are the prescription of anti-inflammatory drugs, bronchodilators and mucolytics. The drugs of choice for anti-inflammatory therapy for OSDP are ICS. Timely prescribed rational therapy for OSDP is the key to rapid relief of OSDP and prevention of life-threatening conditions.

With information support from TEVA LLC

Literature

- Respiratory tract infections in young children / Ed. G. A. Samsygina. M., 2006. 280 p.

- Klyuchnikov S. O., Zaitseva O. V., Osmanov I. M., Krapivkin A. I. et al. Acute respiratory diseases in children. A manual for doctors. M., 2009. 35 p.

- State report of Rospotrebnadzor “Infectious morbidity in the Russian Federation for 2012.” Published on 02/05/2013 on the website https://75. rospotrebnadzor.ru/content/infektsionnaya-zabolevaemost-v-rossiiskoi-federatsii-za-2012-god.

- Global Atlas oF Asthma. Cezmi A. Akdis, Ioana Agache. Published by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2013, p. 42–44.

- Acute respiratory diseases in children: treatment and prevention. Scientific and practical program of the Union of Pediatricians of Russia. M.: International Foundation for Mother and Child Health, 2002.

- Zaitseva O. V. Broncho-obstructive syndrome in children // Pediatrics. 2005, No. 4, p. 94–104.

- Pedanova E. A., Troyakova M. A., Chernyshova N. I. Features of recurrent obstructive bronchitis in young children. In the book: Pulmonology. Adj. 2003. Thirteenth National. congr. by bol. org. breath., St. Petersburg, November 10–14, 2003, p. 188.

- Kotlukov V.K., Blokhin B.M., Rumyantsev A.G., Delyagin V.M., Melnikova M.A. Bronchial obstruction syndrome in young children with respiratory infections of various etiologies: features of clinical manifestations and immune response // Pediatrics. 2006, No. 3, p. 14–21.

- National program “Bronchial asthma in children. Treatment strategy and prevention." 4th ed., revised. and additional M.: Original layout, 2012. 184 p.

- Fisenko V.P., Chichkova N.V. Modern drug therapy of bronchial asthma // Doctor. 2006; 1:56–60.

- Iramain R., López-Herce J., Coronel J. Inhaled salbutamol plus ipratropium in moderate and severe asthma crises in children // J Asthma. 2011 Apr; 48(3):298–303.

- Rachinsky S.V., Tatochenko V.K. Respiratory diseases in children: A guide for doctors. M. 1987. 495 p.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2009 // https://www.ginasthma.org.

- Zhestkov A.V., Svetlova G.N., Kosov A.I. Short-acting b2-agonists: mechanisms of action and pharmacotherapy of bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease // Consilium Medicum. 2008, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 99–103.

- Avdeev S. N., Brodskaya O. N. Sterinebs - new possibilities for nebulizer therapy of obstructive pulmonary diseases // Scientific review of respiratory medicine. 2011; 3: 18–24.

- Avdeev S.N. Nebulizer therapy of obstructive pulmonary diseases // Consilium Medicum. 2011. T. 13. No. 3. P. 36–42.

S. V. Zaitseva, Candidate of Medical Sciences S. Yu. Snitko O. V. Zaitseva, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor E. E. Lokshina, Candidate of Medical Sciences

State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education MGMSU named after A. I. Evdokimov Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Causes of bronchitis

Primary obstructive bronchitis in children is often caused by viruses. The following pathogens affect the bronchial tree:

- parainfluenza virus type 3;

- respiratory syncytial virus;

- enterovirus;

- influenza viruses;

- adenoviruses;

- rhinovirus.

Often the manifestation of obstructive bronchitis in a child is preceded by a cold. The disease is repeatedly caused by other pathogens of persistent infections, which include:

- chlamydia;

- mycoplasma;

- herpesvirus;

- pathogens of whooping cough, parawhooping cough;

- cytomegalovirus;

- mold fungi.

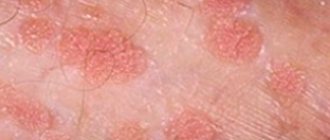

Often, with repeated cases, the opportunistic microflora of the respiratory tract is activated. Allergic reactions play a significant role in the development of bronchial inflammation in children. Relapses of obstructive bronchitis are facilitated by infection with worms and foci of chronic infection (sinusitis, tonsillitis, caries). Factors that provoke the development of exacerbations include:

- physical fatigue;

- hypothermia;

- neuropsychic stress;

- congenital failure of protective barriers;

- unfavorable climate;

- poor environmental stop;

- decreased immunity;

- lack of vitamins.

Passive smoking, as well as irritation of the ciliary epithelium by dust particles and chemicals, play an important role in the development of obstructive bronchial inflammation in children.

ethnoscience

Treatment of obstructive bronchitis with folk remedies does not have evidence-based therapeutic results. And the use of mustard plasters, applications with honey, as well as inhalations with herbs and essential extracts for warming purposes can intensify the phenomena of bronchial obstruction. Complications of the disease:

- Pneumonia, bronchopneumonia

- Chronication of the inflammatory process

- Bronchial asthma

Prevention of obstructive bronchitis:

- Timely treatment and prevention of acute respiratory diseases.

- Vaccination against influenza, Haemophilus influenzae, pneumococcal infection. Premature babies are also vaccinated against respiratory infections.

- Sanitation of foci of chronic inflammation in the oro- and nasopharynx.

- Quitting smoking during pregnancy, in the presence of the child.

- Carrying out general strengthening activities. Spa treatment.

Elimination of allergic background, reduction of allergic readiness.

Pathogenesis of obstructive bronchitis in children

The pathogenesis of the disease has a complex structure. When a virus invades, inflammatory infiltration of the mucous membrane lining the bronchi occurs. Various groups of leukocytes migrate in large numbers in its tissue. Inflammatory mediators are released - histamine, prostaglandin, cytokines. Edema of the bronchial wall develops.

Then the smooth muscle fibers in the wall of the bronchi contract, causing bronchospasm to develop. Goblet cells activate the secretion of bronchial secretions. Mucus has increased viscosity. A disorder of the ciliated epithelium occurs. Mucociliary insufficiency develops. The process of coughing up mucus is disrupted.

The lumen of the respiratory tract is blocked by bronchial secretions. This creates ideal conditions for the proliferation of the bronchitis pathogen. The submucosal and muscular layer of the bronchi is exposed to inflammation. Peribronchial interstitial tissue is included in the process. Lung tissue is not involved in inflammation.

Symptoms

A symptom such as cough with phlegm most often occurs in the morning, during the transition from a state of rest to physical activity, or when leaving a warm room into the cold. Outside of a bacterial exacerbation of obstructive bronchitis, the sputum is mucous; with superinfection, the symptoms are mucopurulent or purulent. Such a symptom as shortness of breath during physical exertion increases gradually. This symptom of obstructive bronchitis increases with infectious exacerbation of obstructive bronchitis. Gradually, the patient notices symptoms of difficulty in exhalation, first after significant physical exertion or during forced exhalation, later during normal exercise and even at rest. Signs of obstructive bronchitis appear: distant dry wheezing or whistling, audible or palpable when you apply your palm to the chest. Also, during the period of infectious exacerbation of obstructive bronchitis, low-grade body temperature, fatigue, sweating, as well as pain in various muscle groups associated with their overstrain when coughing are noted.

Classification and stages of development of obstructive bronchitis in children

There are three forms of obstructive bronchitis - bronchiolitis, acute and recurrent. Bronchiolitis often affects children under 2 years of age. This is how their body responds to the introduction of rhinovirus or respiratory syncytial infection. It is preceded by a mild ARVI. As the condition worsens, respiratory and heart failure develops. With this form, characteristic moist, fine-bubble wheezing appears on inhalation and exhalation.

Acute bronchial obstruction most often occurs in children aged three to five years. It is caused by parainfluenza and influenza viruses, adenovirus. First, the temperature rises to high numbers. Other symptoms of ARVI appear. Then manifestations of respiratory failure increase. The child has difficulty breathing. The muscles of the neck and shoulders are involved in the breathing process. Whistling sounds occur when exhaling. Exhalation becomes difficult and lengthens.

Recurrent obstructive bronchitis occurs at any age. It is caused by: mycoplasma, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, Epstein-Barr virus. Bronchial obstruction increases gradually. This occurs at normal or low-grade fever. Nasal congestion, runny nose and infrequent coughing are noted. Shortness of breath is moderate. The general condition is almost unaffected. According to the course of the disease, the following forms are distinguished: acute, protracted, recurrent and continuously relapsing.

Forms of bronchitis

There are several forms of bronchitis along the way:

- Acute bronchitis is an acute inflammation of the bronchial mucosa.

- Recurrent bronchitis – when a child experiences bronchitis 2-3 times a year.

- Chronic bronchitis is a chronic widespread inflammatory lesion of the bronchi. In this case, the child experiences 2-3 exacerbations of the disease during the year and this continues for at least two or more years in a row.

Fortunately, chronic bronchitis practically never occurs in children. But there are a number of chronic diseases that occur with similar symptoms.

Symptoms of obstructive bronchitis in children

At the onset of the disease, the clinical picture is dominated by manifestations of ARVI. Dyspeptic symptoms are possible in small children. Bronchial obstruction often occurs on the first day of illness. Bronchitis is manifested by the following symptoms:

- increase in respiratory rate (up to 60 per minute);

- prolongation of exhalation;

- dyspnea;

- breathing is noisy, wheezing;

- auxiliary muscles are involved in the act of breathing;

- the anteroposterior size of the chest increases;

- flaring wings of the nose;

- cough with scant sputum, paroxysmal in nature;

- sputum discharge is difficult;

- pale skin;

- cyanosis of the lips;

- cervical lymphadenitis.

Bronchial obstruction persists for up to a week. Then its manifestations gradually subside as inflammation in the bronchi subsides. Children under six months of age develop acute bronchiolitis. Inflammation in the bronchi is accompanied by severe respiratory failure.

Causes of prolonged cough not related to bronchitis:

- sinusitis and postnasal drip syndrome (this is the flow of nasal mucus along the back wall of the pharynx into the respiratory tract). Most patients have mucous or mucopurulent nasal discharge.

- postnasal drip can occur with general cooling of the body, allergic and vasomotor rhinitis, irritating environmental factors;

- Various foreign bodies can enter the child’s bronchi - through swallowing, choking, inhalation;

- oncology, pleurisy - here the diagnosis will be correctly made when additional types of examination are carried out;

- a prolonged cough can be due to heart failure (in this situation, the cough often occurs at night when the child is sleeping); the diagnosis is helped by examination of the chest organs and echocardiography.

- a child may be allergic to various irritants (food, household or plant allergens, taking certain medications, the presence of some animals in the house).

- If a child has a prolonged cough, it is necessary to exclude the infectious disease whooping cough.

Complications of obstructive bronchitis in children

Acute obstructive bronchitis is complicated by the transition to a continuously relapsing form. It is formed against the background of secondary bronchial hyperreactivity. It develops due to various factors: passive smoking, untreated infections, hypothermia or overheating, frequent contacts with people infected with ARVI.

In children under three years of age, bronchitis is complicated by pneumonia. This is associated with difficulties in evacuating thick sputum. It closes the lumen, disrupting the ventilation of the pulmonary segment. When bacterial flora attaches, inflammation develops. This complication occurs rarely. It occurs only in weakened children.

Prevention

In the modern situation, it is necessary to pay great attention to the prevention of bronchitis. Prevention in children is vaccination against various infections. It is important that not only the child is vaccinated, but that everyone around him is also vaccinated. A big role for children is played by hardening, fresh indoor air, adherence to a daily routine, constant physical education, active walks in the fresh air, proper and regular healthy nutrition appropriate for the child’s age, and the use of vitamins.

Diagnosis of obstructive bronchitis in children

To make a diagnosis, the child is examined by a pediatrician or pulmonologist. During the examination, the doctor performs auscultation (listening to the chest with a phonendoscope) and percussion (tapping).

To diagnose obstructive bronchitis, use:

- radiography (fluorography) – required to identify changes in the pulmonary pattern and exclude pneumonia;

- tracheobronchostoscopy - secretion, ulceration of the mucous membrane, fibrin deposits are detected in the bronchi;

- sputum culture tank - examination of material to search for the pathogen with determination of sensitivity to antibiotics;

- detection of antibodies to various viruses;

- PCR to isolate viral antigen;

- spirography - study of external respiration function;

- blood gas analysis;

- Peak expiratory flow study;

- spirography - measures the volume and speed of exhaled air

- skin allergy tests are carried out to exclude the allergic nature of the pathology.

The child is prescribed laboratory tests (general analysis and blood biochemistry, level of C reactive protein).

Diagnosis and treatment of bronchitis

Diagnosis of bronchitis in children is important in the overall treatment program. In addition to the disease itself, diagnosis helps determine the form, stage and possible complications. Bronchitis in children is diagnosed in the following ways1:

- Taking anamnesis from the child and parents;

- Detection of cough and determination of its duration;

- Physical diagnosis, including palpation, general external examination and listening to the chest with a phonendoscope;

- X-ray examination.

In most cases, these diagnostic methods are sufficient, and children tolerate them easily. But other diagnostic methods can also be used: complete blood count, spirometry (measurement of lung volume) and bronchography.

Science has accumulated a lot of knowledge about respiratory diseases and their specific pathogens. Methods of treatment and diagnosis in children are used and well studied, but there is still no universal remedy. Treatment must be comprehensive.

One of the interesting and truly important achievements of science in recent years is the refusal to completely prescribe antibiotics for any form of bronchitis. Considering that the disease most often occurs due to viruses, antibiotics do not show themselves in treating the main problem and greatly harm the fragile child’s body. Treatment with antibiotics is recognized as irrational5.

However, chronic bronchitis that is likely or confirmed to be caused by a bacterial infection must be treated with antibiotics or risk serious complications. Everything depends on an accurate diagnosis and determination of the cause of the disease, and then a competent treatment plan must be built.

In most cases, treatment comes down to helping the body fight the viral infection that caused bronchitis. Immunity must enter the battle; it must be helped and given all the conditions for the fight.

Considering the severity of the course and the various causes of the disease, medications for the treatment of bronchitis in children should be prescribed only by the attending pediatrician or ENT3:

- Antipyretics;

- Antitussives;

- Immunostimulants;

- Antiviral drugs;

- Antiallergic drugs;

- Antihistamines;

- Expectorants, mucolytics and bronchodilators;

- Herbal preparations with expectorant effect;

- Antibiotics for the most serious cases of illness.

In the treatment of children, inhalation methods of drug delivery, chest massage and electrophoresis have proven themselves to be effective. Treatment of bronchitis in children at home should include drinking plenty of fluids, air humidification and hypoallergenic food.

Considering that the main cause of bronchitis is a virus, it is worth focusing on maintaining and developing immunity, especially during the cold season. Ancillary medications may be used to support or restore protective functions. Among them, IRS ® stands out, a complex drug based on bacterial lysates6.

The IRS®19 immunomodulator has stood the test of time7. The drug successfully resists pathogenic bacteria on the mucous membranes of the respiratory system, preventing the spread of infection. Its use can significantly reduce the incidence of respiratory diseases, and also reduces the total need for antibacterial and anti-inflammatory therapy8.

The principle of action of the drug is based on immunostimulation. The composition contains bacterial lysates of common infectious agents. IRS®19 activates and stimulates local immunity, thereby holding the gates through which various respiratory infections try to break in. After using the drug, it is easier for the body to cope with bacteria that can settle on the bronchi6.

Treatment of obstructive bronchitis in children

Children with bronchitis are often treated on an outpatient basis. Indications for hospitalization include age up to one year, the child’s serious condition, and the presence of concomitant pathologies. The main treatment is etiotropic therapy. It includes antiviral or antibacterial drugs.

Pathogenetic therapy includes selective bronchodilators or inhaled glucocorticosteroids. They are inhaled through a compressor nebulizer. The following drugs are prescribed as symptomatic therapy:

- diluting sputum - they facilitate its evacuation;

- expectorants - activate the movements of the cilia and promote coughing;

- antipyretics;

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

- restoratives (vitamins, immunomodulators).

During the recovery period, physiotherapy, massage and breathing exercises are prescribed.

Features of childhood bronchitis

Children often experience types of bronchitis such as allergic or toxic. Symptoms of these forms of the disease may differ. In the first case, symptoms begin to appear, as a rule, after contact with an allergen: plant pollen, animal hair, dust, etc. Usually the cough is dry, without sputum, and the body temperature remains within normal limits or remains at a level of up to 38 ° C for a long time. With toxic bronchitis, symptoms develop after contact with a chemical in air that is polluted or, for example, containing tobacco smoke. Breathing is harsh, cough is unproductive, and body temperature rises slightly. The child may complain of dizziness.

How to cure bronchitis in a child

Treatment of bronchitis in children begins with creating favorable conditions for recovery. Basic recommendations from the doctor:

- compliance with bed rest;

- drinking plenty of warm drinks - this measure helps reduce the viscosity of mucus and facilitate its removal;

- indoor air humidification;

- maintaining a temperature of 18–23 °C in the room;

- regular wet cleaning of the premises, ventilation;

- a light diet, at the child's request - dairy-vegetable, limiting roughage, spices, hot dishes and drinks.

The basis of treatment is drugs aimed at alleviating the symptoms of the disease, because in most cases, acute bronchitis goes away on its own and without treatment. It is important to alleviate the child’s condition, reduce the time of illness and prevent the development of complications. . Bronchitis of a bacterial nature requires the use of antibiotics.

The effectiveness of antiviral drugs has not been proven, with the exception of the use of special drugs for influenza.

Fungicidal, or antifungal, therapy is rarely used. The allergic form of bronchitis requires the use of antihistamines (antiallergic) drugs. It is important to isolate the child from harmful factors both in case of toxic bronchitis and other types of the disease.

Also, almost all forms of the disease involve the use of mucolytics - drugs that facilitate the discharge of sputum. Plant-based products can complement therapy. For example, Bronchipret® is a natural herbal preparation for acute coughs that helps relieve inflammation, improve mucus discharge and inhalation of the lungs due to the high concentration of thyme essential oils. Its use at the first symptoms reduces the likelihood of complications.

Danger

Acute obstructive bronchitis is well treated. If a child is prone to allergies, the disease can often recur, which can lead to the development of bronchial asthma or asthmatic bronchitis. If the disease becomes chronic, the prognosis is less favorable.

In 5% of cases, the disease is accompanied by a secondary infection that affects one or two lungs at once. Then pneumonia is diagnosed. Most often, complications of obstructive bronchitis occur in smokers, people with weakened immune systems, and people with liver, kidney and heart diseases. It can be:

- respiratory failure;

- emphysema;

- amyloidosis (disorder of protein metabolism in tissues);

- pulmonary heart.

If the patient begins to choke, feels severe weakness, and refuses to eat, an urgent consultation with a pulmonologist is necessary. In severe cases, hospitalization may be required.