Spectrum of action

The activity of drugs from the cephalosporin group gradually changes from generation to generation:

- Medicines of 1-2 generations are most effective against infection with gram-positive flora (staphylo- and streptococci, corynebacteria).

- For the 3rd and 5th generations of cephalosporins, there is already an increased activity against gram-negative bacteria (Enterobacter, Haemophilus influenzae, gonococcus, meningococcus, Klebsiella, Moraxella, Proteus) and anaerobes (peptococcus, peptostreptococcus, clostridia, bacteroides) along with high efficiency against gram-positive flora. In addition, ceftazidime and cefixime are harmful to Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- 4th generation cephalosporins are different: their effect is maximum for gram-negative bacteria, while cefepime also has an antipseudomonas effect.

Antibiotics from the cephalosporin series are classified as β-lactam antibiotics. Each of their representatives has 7-ACC (7-aminocephalosporanic acid) in its structure and is characterized by higher resistance to the special bacterial enzyme β-lactamase. By preventing the synthesis of components of the cell wall of bacterial cells, cephalosporins realize their bactericidal effect, i.e. completely destroy microbial cells.

Myth. Modern antibiotics are so “strong” that not a single bacteria can resist them.

Is it true.

In fact, one of the most pressing problems of modern pharmacology and healthcare in general is the rapid development of resistant strains of bacteria, which are also resistant to modern antibiotics of the latest generations. The emergence of resistance has been registered for each class of antimicrobial drugs without exception. It can develop at any stage of achieving a therapeutic effect (and even several at once). The main mechanisms for the development of resistance [1, 2]:

- Initially resistant strains. For example, some gram-negative bacteria have outer cell membranes that protect their cells from the action of a number of penicillins and cephalosporins.

- Spontaneous mutations leading to the emergence of organisms resistant to antibiotics.

- The transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes is the most common and important mechanism for the development of antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic resistance is a global problem that can have unpredictable consequences for each of us. Alas, consumers themselves make a huge contribution to its existence. It is appropriate to remind customers of this with prescriptions for antibiotics, emphasizing that the risk of developing resistant strains can be significantly reduced by taking antimicrobial drugs only as prescribed by a doctor and strictly observing the dose and regimen of antibiotic therapy.

Common representatives

Of the numerous list of cephalosporins, the most frequently used at the moment are representatives of the 3rd generation, namely ceftriaxone, ceftibuten, cefditoren. This is due to their wide spectrum of action and relatively low cost. In addition, the last two drugs are available in oral form, which is very convenient for patients to take.

It may seem that cephalosporins, available in tablet form, are rarely used drugs. This is not true: such drugs are applicable even for severe infections of various organs, when other antibiotics do not have the desired effect.

It is advisable to compare the most common representatives according to a number of important criteria:

Speed of effect (time of maximum concentration in blood):

| Ceftriaxone | Ceftibuten | Cefditoren |

|

|

|

Microbial spectrum of action:

| Ceftriaxone | Ceftibuten | Cefditoren |

| ||

|

|

|

Resistant strains of bacteria:

| Ceftriaxone | Ceftibuten | Cefditoren |

|

|

|

Side effects:

| Ceftriaxone | Ceftibuten | Cefditoren |

| Nervous system | ||

|

|

|

| Cardiovascular system, hematopoiesis | ||

|

|

|

| Gastrointestinal tract | ||

| ||

| Genitourinary system | ||

|

|

|

| Allergic reactions | ||

|

|

|

Use in pregnant and lactating patients:

| Ceftriaxone | Ceftibuten | Cefditoren |

|

|

|

See How to distinguish coronavirus from acute respiratory viral infections, flu, and colds. Pneumonia with coronavirus: symptoms, treatment Nobasit for covid Ingavirin for coronavirus Symptoms and treatment of coronavirus

Strategic approaches to the selection of cephalosporin antibiotics for respiratory tract infections

The problem of rational antibiotic therapy remains one of the most difficult in clinical practice. If previously a doctor, when choosing a drug, was guided by its effectiveness, tolerability and safety, today this is not enough. The factor of convenience of taking the drug and, which is especially unusual for our understanding, the issues of price and cost of treatment in conditions of serious restrictions on healthcare financing can often be decisive. Medical institutions spend 15–20% of their budget on the purchase of medicines, and 50–60% of these costs fall on antibacterial drugs, which forces them to reconsider existing ones and look for new approaches to their use.

The confusion that arises when using various antibacterial drugs, including cephalosporin antibiotics (CA), is associated with misunderstanding or simply ignorance of the basic principles of clinical chemotherapy. In this regard, we would like to dwell on some mistakes and “misconceptions” of practicing physicians that arise when prescribing antibacterial drugs, using the example of CA, and also determine their place in the treatment of respiratory tract infections.

Often we hear from practicing doctors about the unconditional advantages of the IV generation of drugs over the III, III generation over the II, etc. This is absolutely false. This point of view leads to the use of “reserve” and powerful drugs in the treatment of a banal infection, promotes the development of resistance, and therefore makes it impossible to use first-generation drugs and, finally, causes a significant and unjustified increase in the cost of treatment.

CAs occupy an important place in the treatment of upper and lower respiratory tract infections. The most critical step in antibacterial therapy for this category of patients is the choice of the initial drug. The effectiveness and safety of treatment, as well as its comfort, tolerability, cost, and epidemiological situation depend on the adequacy of the choice.

Analysis of available data on the use of target audiences in Russia for 1997–1998. allows doctors to identify preferences for a particular drug (group of drugs) and certain methods of its administration. As can be seen from Fig. 1, when prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics, the vast majority of doctors choose parenteral drugs.

This fact only confirms that in our country oral medications, and especially oral cephalosporins, are very little popular and are practically not used. This attitude towards tablet forms reflects a certain conservatism of practical doctors, due to the fact that even 15-20 years ago the then existing oral drugs could not be compared with parenteral drugs either in terms of the effectiveness of therapy or its tolerability. Only in recent decades since the creation of the first oral cephalosporin, cephalexin, and the advent of new oral bactericidal drugs, has this dosage form somewhat strengthened its position not only in outpatient, but also in inpatient practice. However, this did not radically affect the state of affairs.

It is obvious that this form of drug administration has undoubted advantages. This is manifested in the possibility of outpatient management of the patient, and in the convenience of taking the drug, and in reducing the risk of post-injection complications and length of hospital stay, and even in getting rid of the psychological discomfort associated with injections.

The presence of antibacterial drugs in two forms - for parenteral and oral use - makes it possible to use them for so-called step therapy. The essence of such treatment is to prescribe an intravenous or intramuscular drug and then, two to three days after achieving a clinical effect, transfer it to oral administration. The possibility of carrying out stepwise therapy with the same drug is a significant advantage of this drug over its analogues. Stepped therapy provides clinical and economic benefits to both the patient and the healthcare facility.

Based on the data presented, it is difficult to understand the logic of choosing a cephalosporin antibiotic of one generation or another and the principles that guide the doctor when prescribing the drug. Analysis of the use of cephalosporin antibiotics by generation (see Fig. 2 and 3) indicates the preferred use of drugs of the 1st and 3rd generations, with half of the 3rd generation drugs (61%) being cefotaxime, and the majority of the 1st generation drugs being cefazolin.

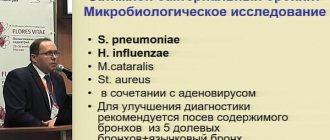

In clinical practice, the doctor begins to administer antibacterial therapy, in most cases without the results of microbiological verification of the infectious agent, and often without the prospect of obtaining this kind of data. Therefore, when choosing an antibacterial drug, one still has to rely on information obtained from the literature, microbiological monitoring data, as well as the characteristics of the clinical situation. All this makes it possible, with a greater or lesser degree of probability, to determine the etiological infectious agent, taking into account the clinical form of respiratory tract infection (pneumonia, chronic bronchitis, sinusitis, etc.), age (children, old people), concomitant diseases (diabetes mellitus, chronic alcohol intoxication , treatment with glucocorticoids and cytostatics). It is also necessary to keep in mind the peculiarities of the development of infection in an outpatient setting or in a hospital (treatment for another disease, stay in intensive care) in the corresponding epidemiological situation. It should be noted that when choosing a drug, it is important to distinguish a “hospital” or nosocomial infection that occurs two days after admission to the hospital, from an “outpatient” infection that is treated in a hospital. In the latter case, the tactics of antibacterial therapy should differ significantly.

Thus, the approximate etiology of bronchopulmonary infection serves as the basis for choosing among CA a specific drug (or generation of drugs) with appropriate antimicrobial activity.

In patients with outpatient infection of the upper and lower respiratory tract, the main pathogens of which are streptococci, H. influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, the drugs of choice may be I or II generation CA. In outpatient settings, preference should be given to oral cephalosporins (cefaclor, cefuroxime axetil, ceftibuten). At the same time, it is necessary to keep in mind the insufficient activity of CA in general against atypical bacteria (8–35% in the etiology of “domestic” pneumonia) and some anaerobic microorganisms, the likelihood of which increases in patients with chronic sinusitis and otitis.

During exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, drugs that are highly resistant to the action of b-lactamases produced by both gram-negative and gram-positive microorganisms (cefuroxime axetil) and have high activity against H. influenzae (ceftibuten) become of particular importance.

When identifying indications for hospitalization of patients with a “domestic” infection, implying a more severe course, Streptococcus pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, H. influenzae and Enterobacteriacea are more often detected. In this case, the prescription of parenteral cephalosporins of the second generation (cefuroxime, cefamandole) is more justified. However, it is precisely in such situations that mistakes are most often made: when a patient is hospitalized in a hospital with “domestic” pneumonia, benzylpenicillin, aminopenicillins and first-generation CAs are often prescribed (ineffective due to the high resistance of the pathogenic flora), or, for “reinsurance”, even in the presence of , III generation CA (cefotaxime, less often ceftriaxone). However, it is more reasonable - and this is determined by the spectrum of activity of the drug - to prescribe CA II. Among patients receiving hospital treatment for lower respiratory tract infections, mild cases predominate. Therefore, the ideology of prescribing second-generation CAs as “starter” drugs should dominate both from the position of adequate clinical effectiveness, economic feasibility, and from the position of maintaining a reserve in more severe situations.

The choice of CA as the initial antibiotic for community-acquired pneumonia in patients under 60 years of age without concomitant pathology should, apparently, not always be considered justified. This is due to the etiologically wide spectrum of pneumonia in this situation, which may include not only pneumococci and H. influenzae, but also the so-called atypical pathogens - Mucoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella, Chlamidia pneumoniae, which are not sensitive to cephalosporins of all generations. Meanwhile, rational empirical antibacterial therapy for bronchopulmonary infections, including pneumonia, should include the choice of a drug that is, if possible, active against all pathogens likely in a given situation. Unfortunately, today it is difficult to name a drug that fully satisfies these requirements, with the exception of the new generation of fluoroquinolones or “respiratory” fluoroquinolones. Some of them, for example, grepafloxacin, are currently being registered in our country. In cases of prescribing CA for this type of pneumonia, preference should be given to CA of the first and second generation. The use of third-generation CAs in such situations is irrational due to the high risk of developing resistance. The choice of a specific drug among I-II generation CAs should be based on the advantages of dosage forms, pharmacokinetic properties, cost, etc. For mild pneumonia, oral cephalosporins can be prescribed. In this case, it is necessary to keep in mind their different antimicrobial activity towards different microorganisms. For example, ceftibuten has the greatest activity against H. influenzae, and cefuroxime axetil has the greatest activity against S. aureus.

The general principles for choosing the initial CA remain in patients with pneumonia against the background of severe concomitant diseases (COPD, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, alcohol intoxication, etc.) and over the age of 60 years. H.influenzae, S.аureus, and some gram-negative microorganisms (E.coli, Clebsiella) acquire etiological significance in this clinical situation, and the frequency of beta-lactamase-producing bacteria increases. In this regard, the importance of drugs active against these pathogens is increasing. It is known that the antimicrobial effect of CA during the transition of activity from the first generation to subsequent ones is characterized by a decrease in antistaphylococcal activity and a predominance of activity against some gram-negative microorganisms. A valuable property is the resistance of second-generation CA to b-lactamases. In this regard, the doctor should focus in this situation on cephalosporins of the second or at least third generation.

A different approach that determines the choice of CA for the treatment of bronchopulmonary infection is observed in patients with “hospital” infection. Hospital-acquired pneumonia occupies a special place among all nosocomial infections due to the severity of the course and the difficulties of therapy. The main causative agents of hospital-acquired pneumonia are gram-negative microorganisms of the Enterobacteriacea family - Clebsiella, Protei, Enterobacter, Providencia, Serracia, as well as Staphylococcus aureus, both sensitive and resistant to methicillin. The likelihood of the etiological role of a particular infectious agent in hospital-acquired pneumonia is determined by the characteristics of the clinical situation (postoperative period, stay in intensive care, artificial ventilation, etc.). In patients in intensive care and burn departments, with immunodeficiencies and cystic fibrosis, the main microorganism of bacterial complications is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, detected in 70–95% of cases. Along with it, such patients are sown with Staphylococcus aureus or Haemophilus influenzae, resistant to CA II–III generations. The main place in the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia among CA is occupied by drugs of the III (ceftazidime, cefoperazone) and IV generations (cefpirome, cefepime). Taking into account the likelihood of the etiological role of Pseudomonas aeruginoza in appropriate situations (ventilation, the presence of a tracheostomy, previous glucocorticoid therapy), prescribed CAs should have antipseudomonas activity. Among the CAs available to the doctor, the third generation cephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefoperazone) and IV generation (cefpirome) have the greatest activity against Pseudomonas aeruginoza, which, however, do not have serious advantages over ceftazidime against Pseudomonas aeruginoza. The appearance of IV generation CA in the therapeutic arsenal expands the possibilities of antibacterial therapy for hospital-acquired pneumonia with a high probability of gram-negative flora, including Staphylococcus aureus, and can be considered as drugs for urgent situations.

| Cephalosporins, discovered more than 50 years ago, continue to occupy a strong position in the treatment of various bacterial diseases, despite the emergence of new antimicrobial agents. Cephalosporin antibiotics are divided into four generations, differing in their spectrum of action, antibacterial activity, stability in the presence of b-lactamases, and pharmacokinetic profile. All this, along with the variety of dosage forms and cost, determines their various indications. It is obvious that as new generations of cephalosporin antibiotics appear in clinical practice, an important problem arises in the differentiated prescription of the drug, taking into account the properties of both the antibiotic itself and the characteristics of the infectious and inflammatory process in a particular patient |

Thus, the rational choice of the initial CA for the treatment of upper and lower respiratory tract infections is determined primarily by the likelihood of the etiological role of a particular microorganism in a specific clinical situation. This approach requires the practitioner (namely, the adequate choice of drug depends on him) to be able to identify the characteristics of each case of pneumonia (epidemiological situation, background pathology, risk factors, etc.) and navigate the antimicrobial spectrum of the prescribed antibiotic. However, in clinical practice, when choosing CA, as well as other antibiotics, it is necessary to take into account other factors along with the approximate etiology of bronchopulmonary infection. Among the latter, the pharmacokinetics of the drug, the availability of various dosage forms, the risk of side effects, cost, etc. are important.

At present, the place of third-generation oral drugs in clinical practice has not been definitively determined, since their comparative clinical and bacteriological effectiveness differs little from that of second-generation drugs. Moreover, as mentioned above, the advantage of third-generation cephalosporins is their high activity against b-lactamase-producing bacteria, which most often cause serious hospital infections. But since in this case the patients are in the hospital, it is more reasonable to receive parenteral therapy. At the same time, due to reduced activity against gram-positive bacteria, which are often the cause of outpatient infections, the use of third-generation drugs has fewer advantages over second-generation drugs.

The goal of antibacterial therapy is not only to achieve a clinical effect, but also to completely eradicate the pathogen, i.e., bacteriological effectiveness. This is mainly determined by adequate dosing of the drug to achieve the required concentration at the site of infection. A high degree of drug accumulation in tissues is a necessary requirement for a medicinal substance.

First-generation CAs penetrate tissues less well, which reduces the degree of bacterial eradication.

Data on the bioavailability of oral CA should be kept in mind when differentially prescribing them to patients with concomitant intestinal pathology associated with malabsorption, as well as when taking antisecretory drugs and antacids simultaneously, taking into account the effect of food on the absorption of CA.

Knowledge of the ways of eliminating CA, along with an assessment of the functional state of the liver and kidneys (age, concomitant pathology) can also determine the choice of a more adequate drug for a given situation. When choosing CA for the treatment of severe hospital-acquired pneumonia, for example, in newborns and the elderly or in patients with kidney pathology, in the presence of renal failure, preference should be given to cefoperazone, taking into account its predominantly biliary excretion.

When making a differentiated choice of CA, it is necessary to take into account the risk of side effects. The most typical reactions are hypersensitivity reactions (fever, skin rash), hematological syndromes (cytopenia, eosinophilia), disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), liver (increased transaminase activity), kidneys (increased creatinine levels), central nervous system ( headache), phlebitis with intravenous administration. Therefore, anamnestic and clinical laboratory data on the presence of any pathology in patients should influence the choice of the appropriate drug.

Phlebitis often occurs when cephalothin, cefotaxime, or cefepime are administered. Cefuroxime, cefoperazone, ceftibuten can cause anemia (usually hemolytic), and when cephalothin, cefamandole, cefotaxime, ceftazidime are prescribed, antibodies fixed on erythrocytes are sometimes detected. An increase in the activity of liver enzymes is possible during treatment with cefoperazone, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefuroxime. Creatinine levels may increase during treatment with cephalexin and cefpodoxime. Oral cephalosporins most often cause gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). When treated with parenteral CA, an increase in prothrombin time was noted, with the exception of ceftazidime, which does not affect the synthesis of prothrombin complex factors and blood clotting parameters. Hypersensitivity reactions (skin rash, fever, eosinophilia) are possible with the use of almost all third-generation CAs.

Thus, the differentiated choice of CA for the treatment of upper and lower respiratory tract infections should be based on taking into account and adequately assessing many factors, including both the characteristics of the clinical situation and the antimicrobial activity and pharmacokinetic characteristics of the prescribed drug.

Classification of cephalosporins

The series of cephalosporins includes drugs of five generations. Their division into groups occurred gradually, parallel to the discovery of new substances and their properties. Within each generation, oral (taken by mouth) and parenteral (entered into the body through injection) forms are distinguished.

1st generation:

| Representatives | Tradename | Method of application, price |

| Cefazolin (parenteral) | Cefazolin | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 0.5 g. (diluted in 2 ml of sterile water) – 2.0 g. (diluted in 4 ml of sterile water) per day in 3-4 doses, administered intravenously. 20-910 rub. |

| Cefazolin-AKOS | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 0.5 g each. x 2 times a day intravenously (diluted in 5 ml of sterile water) or intramuscularly (diluted in 2 ml of sterile water). 30-50 rub. | |

| Cephalothin (parenteral) | Cephalothin | Powder for making an injection solution: 0.5-1.0 g. every 6 hours intravenously or intramuscularly. 800-1000 rub. |

| Cephalexin (parenteral, oral) | Cephalexin | Capsules: 0.25-0.5 g. every 6 hours, washed down with water, 30-60 minutes before meals. 80-120 rub. |

| Granules for preparing a suspension inside a bottle: add 80 ml of distilled water, shake, drink the resulting mixture according to a measuring spoon (the bottle contains 0.25 g of substance). 1.0-2.0 gr. per day, while 1 ml of the finished mixture contains 25 mg of cephalexin. 80-100 rub. | ||

| Ecocephron | Capsules: 0.25-0.5 g. every 6 hours, washed down with water, 30-60 minutes before meals. 80-100 rub. | |

| Cefadroxil (oral) | Duracef | Capsules, tablets, granules for suspension are excluded from the register of used drugs in the Russian Federation. |

| Biodroxyl |

2nd generation:

| Representatives | Tradename | Method of application, price |

| Cefuroxime (parenteral, oral) | Zinatsef | Powder for making an injection solution: 0.75-1.5 g. intravenously x 3 times a day. 130-250 rub. |

| Zinnat | Capsules: 0.25-0.5 x 2 times a day after meals. 220-400 rub. | |

| Granules for preparing a suspension orally in a bottle: 0.125-0.25 g. per day during meals. 250-330 rub. | ||

| Axoseph | Tablets: 0.25-0.5 g. x 2 times a day. 400-600 rub. | |

| Powder for making an injection solution: 0.75-1.5 g. intravenously x 3 times a day. Maximum 6.0 g. per day. 120-250 rub. | ||

| Cefamandole (parenteral) | Tzefat | Powder for making an injection solution: 0.5-1.0 g. every 6 hours intramuscularly (dissolved in 3 ml of sterile water) or intravenously (dissolved in 10 ml of isotonic sodium chloride). 120-360 rub. |

| Cefaclor (oral) | Ceclor | Capsules, tablets, granules for suspension are excluded from the register of used drugs in the Russian Federation. |

| Cefaclor Stada | ||

| Alphacet |

3rd generation:

| Representatives | Tradename | Method of application, price |

| Cefotaxime (parenteral) | Claforan | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 0.5-2.0 g. (depending on the infection) x 1 time per day intramuscularly (first dissolving 1.0 g in 4 ml, 2.0 g in 10 ml of sterile water) or intravenously (first dissolving in 40-100 ml of sterile water) slowly. 130-150 rub. |

| Cephosin | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0 g. every 8-12 hours intramuscularly (dissolving 1.0 g in 4 ml of sterile water), slowly intravenously (first dissolving 1.0 g in 4 ml, 2.0 g in 10 ml of sterile water) or drip ( 50-100 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution per 1.0-2.0 g of substance). 50-70 rub. | |

| Ceftazidime (parenteral) | Fortum | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0-6.0 g. x 1 time per day in 2-3 intravenous or intramuscular infusions. 450-520 rub. |

| Ceftidine | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0-6.0 g. x 1 time per day (usually 1.0 g every 8 hours) intravenously or intramuscularly. 150-200 rub. | |

| Ceftriaxone (parenteral) | Ceftriaxone | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0-2.0 g. x 1 time per day intramuscularly/intravenously. 30-900 rub. |

| Azaran | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0 g. dissolve in 3.5 ml of 1% lidocaine hydrochloride solution, apply intramuscularly once a day. 2300-2700 rub. | |

| Cefoperazone (parenteral) | Cephobid | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 2.0-4.0 g. per day intramuscularly, dividing the total daily dose into 2 doses. 250-300 rub. |

| Tsefpar | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 2.0-4.0 g. per day intravenously or intramuscularly, divide the dose into equal parts every 12 hours. 30-100 rub. | |

| Cefixime (capsules, suspension) | Suprax | Capsules: 0.4 g. once a day. 700-780 rub. |

| Pantsef | Tablets: 0.4 g. x 1 time per day or 0.2 g. x 2 times a day. 380-590 rub. | |

| Granules for preparing a suspension inside a bottle: shake the bottle well, add 66 ml of boiled water at room temperature, shake again, take 0.4 g. x 1 time per day or 0.2 g. x 2 times a day (using a measuring cap). 390-700 rub. | ||

| Suprax Solutab | Effervescent tablets: 0.4 g. x 1 time per day or 0.2 g. x 2 times a day, dissolved in a glass of water. 800-1000 rub. | |

| Ceftibuten (capsules) | Tsedex | Capsules: 0.4 g. x 1 time per day. 800-1100 rub. |

| Cefditoren (in tablets) | Spectraceph | Tablets: 0.2/0.4 g. twice a day. 1300-1400 rub. |

4th generation:

| Representatives | Tradename | Method of application, price |

| Cefepime (parenteral) | Maxipim | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 0.5-2.0 g. every 12 hours, administered slowly intravenously (diluted in 5/10 ml of sterile water) or intramuscularly (diluted in 1.3/2. ml of sterile water). 350-400 rub. |

| Cefepime | Powder for making an injection solution: 0.5-1.0 g. every 12 hours, intravenous or intramuscular administration (dilution volumes are similar). 120-150 rub. | |

| Cefpir (parenteral) | Cefanorm | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 1.0-2.0 g. intravenously every 12 hours. 1300-1500 rub. |

| Izodepom | Powder for making an injection solution: 0.25/0.5/1.0/2.0 g, dividing the administration in half every 12 hours. Administer intravenously slowly/drip or intramuscularly (dilute the dose in 25/50/100/200 ml of sterile water or isotonic sodium chloride solution, respectively). 600-900 rub. |

5th generation:

| Representatives | Tradename | Method of application, price |

| Ceftobiprole (parenteral) | Zeftera | Lyophilisate for the manufacture of injection solution - excluded from the register of used drugs in the Russian Federation. |

| Ceftaroline (parenteral) | Zinforo | Powder for the preparation of injection solution: 0.6 g each. every 12 hours as an intravenous infusion for 60 minutes (after adding 20 ml of sterile water to the powder, shake the resulting mixture and transfer it to a bottle, where add 50/100/250 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution). 25000-27000 rub. |

The combination of cefoperazone + sulbactam in parenteral preparations was created specifically to protect against the destructive effects of bacterial β-lactamase enzymes:

- Sulperazone (powder for the preparation of an injection solution: 1.0-2.0 g of cefoperazone + 1.0-2.0 g of sulbactam in a 1:1 ratio, dividing the dose into 2 doses, administered intravenously, intramuscularly). 480-550 rub.

- Sulperacef (powder for the preparation of an injection solution: 0.5-1.0 g cefoperazone + 0.5-1.0 g sulbactam in a 1:1 ratio, administered intramuscularly or intravenously every 12 hours). 2400-3000 rub.

All drugs from the list of cephalosporins are absolutely prohibited for use together with alcoholic beverages of any strength. Otherwise, the antabuse effect develops - an acute, deadly toxic effect on the body in the form of respiratory disorders, cardiac activity and bronchospasm.

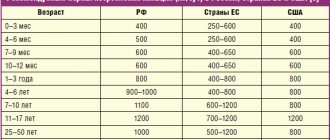

Use in childhood

Antibiotics of the cephalosporin group are for the most part not contraindicated for use in pediatric patients. Average daily dosages for children are:

| Cephalosporin | Dose |

| Cefazolin |

|

| Cephalothin | 0.02-0.04 g/kg per day, dividing the administration every 6 hours. |

| Cephalexin |

|

| Cefuroxime |

|

| Cefamandole |

|

| Cefotaxime |

|

| Ceftazidime |

|

| Ceftriaxone |

|

| Cefoperazone | 0.05-0.2 g/kg per day (administer 2 times). |

| Cefixime |

|

| Ceftibuten |

|

| Cefditoren |

|

| Cefepime |

|

| Cefpir |

|

| Ceftaroline | There is no complete information about the safety and effectiveness of the drug in children under 18 years of age. |

Cephalosporins of all generations do not lose their relevance at the present stage of development of medicine. Due to the wide spectrum of action of these drugs, it is possible to cure a wide range of infectious diseases. Unfortunately, microorganisms are constantly changing their structure, trying to become immune to the harmful effects of antibiotics. To avoid this, do not take antibacterial drugs without a doctor's prescription.

Author:

Selezneva Valentina Anatolyevna physician-therapist