Currently, in the structure of surgical interventions for primary and metastatic liver tumors, the first place is occupied by extensive liver resections, which are characterized by high morbidity and often massive intraoperative blood loss [1]. In recent years, the immediate results of extensive liver resections, according to modern literature, have improved markedly. Thus, in the early 90s, mortality after liver resections performed for cancer ranged from 20 to 33%. Today, this figure does not exceed 2-6% and is determined mainly by massive intraoperative blood loss and post-resection liver failure [8]. In recent years, there has been a tendency to reduce the volume of blood loss during such surgical interventions. A number of researchers indicate that, against the backdrop of a favorable trend, the average volume of blood loss during liver resections still exceeds 2000 ml, which cannot be satisfied at the current stage of development of medicine [3].

Massive blood loss leads to hypovolemia, anemia, decreased perfusion of organs and tissues, which leads to impaired oxygen delivery, the formation of oxygen debt and the occurrence of multiple organ failure syndrome [4]. In addition, the loss of platelets and plasma coagulation factors leads to hypocoagulation and consumptive coagulopathy, which, against the background of trauma, the presence of an extensive wound surface and oxygen deficiency of tissues, can result in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) syndrome [5].

Currently, blood-saving technologies are divided into technical and pharmacological. Technical blood-saving technologies include the use of devices for reinfusion of spilled autologous blood (Cell Saver), modern surgical scalpels (harmonic) and coagulators (argon plasma). Pharmacological technologies include the procurement of autologous blood, normovolemic hemodilution, the use of fibrinolysis inhibitors, activators of the platelet component of hemostasis, and the maintenance of relative hypovolemia [6]. An important feature of liver surgery is often the absolute impossibility of ligating a bleeding vessel. This is why it is so important to maintain relative hypovolemia and strive for rapid clot formation in the damaged vessel [6].

In this regard, the possibility of influencing the muscle tone of the walls of small vessels is of interest. Our institute assessed the possibility of perioperative use of terlipressin (Remistip, FERRING-Lechiva a.o., Czech Republic), the active substance of which is a synthetic analogue of the posterior pituitary hormone vasopressin. In the human body, terlipressin undergoes biotransformation and turns into active metabolites that have pronounced vasoconstrictor and hemostatic effects. However, unlike vasopressin, terlipressin does not have a clinically significant antidiuretic effect. Active metabolites of terlipressin cause spasm of arterioles and venules mainly in the parenchyma of internal organs, contraction of smooth muscles of the esophageal wall, increased tone and intestinal motility. Terlipressin has a long-term effect, the maximum concentration of the drug in the blood is reached 60-120 minutes after administration, a stable hemostatic effect persists for 4-6 hours [7]. It has been shown that when performing hysterectomy with resection of the greater omentum for ovarian cancer, the use of terlipressin can reduce the amount of total blood loss by 40%. Terlipressin has no effect on blood coagulation parameters, which is important for cancer patients with initial signs of hypercoagulation syndrome [2].

The purpose of the study was to analyze the intraoperative use of terlipressin to reduce blood loss and evaluate the effect of the drug on the results of surgical treatment of cancer patients with extended liver resections along with traditional blood-saving technologies.

Pharmacological properties of the drug Glipressin

Pharmacodynamics . Terlipressin is a synthetic analogue of the posterior pituitary hormone vasopressin. Terlipressin reduces the pressure in the portal vein system and portal blood flow, causing spasm of the esophageal muscles with further narrowing of esophageal varices. Biologically active lysine vasopressin is slowly released from the inactive prohormone terlipressin. Metabolic elimination of lysine vasopressin occurs in parallel with release, so its concentration in the blood plasma from minimal to subtoxic remains for 4–6 hours. Terlipressin increases the tone of smooth muscles in the vessels and gastrointestinal tract. An increase in peripheral vascular resistance leads to a decrease in the trophism of nerve fibers innervating internal organs. A decrease in arterial perfusion leads to a decrease in pressure in the portal venous system. The simultaneous contraction of the muscular membranes of different parts of the intestine is manifested by increased peristalsis. The contracting muscles of the esophageal wall compress the varicose nodes. The antidiuretic effect of terlipressin is only 3% of the activity of native vasopressin, so it is not clinically significant. With normovolemia, renal blood flow does not change significantly, but increases with hypovolemia. Terlipressin has a slow hemodynamic effect over 2–4 hours. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure increases slightly. In renal hypertension and generalized atherosclerosis, a pronounced increase in blood pressure was observed. Even when the drug is used in high doses, terlipressin does not have a cardiotoxic effect. Under the influence of terlipressin, blood flow in the endometrium and myometrium is significantly reduced. Due to the vasoconstrictive effect of terlipressin, blood flow in the skin is reduced, which is manifested by pallor of the skin. Hemodynamic and smooth muscle effects are the main pharmacological effects of terlipressin. Centralization of blood circulation during hypovolemia is considered as a compensatory protective reaction during bleeding from varicose veins of the esophagus. Pharmacokinetics . Terlipressin is pharmacologically inactive. The active metabolite of terlipressin, lysine vasopressin, is characterized by slow release due to the destruction of the latter. The glycine residue is easily excreted in free form upon cleavage of triglycyl nonapeptide. The average T1/2 of terlipressin is 24±2 min. After IV bolus administration, terlipressin is eliminated according to second-order kinetics. The half-life in the distribution phase (duration - up to 40 minutes) is 12 minutes. Upon cleavage of the free glycine residue, the hormone lysine vasopressin is released slowly and reaches a peak concentration after 120 minutes. Only 1% of terlipressin is detected in urine, since the drug is completely metabolized with the participation of endo- and exopeptidases of the liver and kidneys.

Efficacy and safety of terlipressin for cesarean section in pregnant women at high risk of bleeding: the multicenter, omnidirectional Terli-Bleed cohort study. Part I

Y.S. Raspopin (Regional Clinical Center for Maternal and Child Health, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Prof. V.F. Voino-Yasenetsky, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation), E.M. Shifman (Moscow Regional Scientific -Research Clinical Institute named after M.F.Vladimirsky, Moscow, Russian Federation), A.A. Belinina (Altai Regional Clinical Perinatal Center, Barnaul, Russian Federation), A.V. Rostovtsev (City Clinical Emergency Hospital No. 8 , Voronezh, Russian Federation), N.V. Artymuk (Kemerovo State Medical University, Kemerovo, Russian Federation), A.S. Olenev (City Clinical Hospital No. 24, Moscow, Russian Federation), V.B. Tskhai (Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Prof. V.F. Voino-Yasenetsky, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation, Federal Medical and Biological Agency of Russia, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation), Yu.S. Aleksandrovich (St. Petersburg State Pediatric Medical University, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation), I.V. Molchanova (Altai Regional Clinical Perinatal Center, Barnaul, Russian Federation), O.N. Novikova (Kemerovo State Medical University, Kemerovo, Russian Federation)

Prevention of postpartum hemorrhage is one of the important tasks of modern obstetrics, anesthesiology and intensive care.

Target

. To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of terlipressin as a means of preventing the development of postpartum hemorrhage during cesarean section in high-risk pregnant women.

Patients and methods.

A multicenter, omnidirectional cohort study was conducted from February to December 2021, involving 5 medical centers. The study included 454 pregnant women who delivered by cesarean section, who were divided into two groups: group I (n = 351) - control, group II (n = 103) - study, with the use of terlipressin injected into the thickness of the myometrium. The assessment of the preventive effect of the drug was carried out in several main areas: the volume of blood loss, the need for additional methods of surgical hemostasis, and the safety of intraoperative use.

Results.

Significant differences were identified when assessing significant risk factors for the development of postpartum hemorrhage, comorbidities and comorbid conditions between groups. The study group was more at risk of developing postpartum hemorrhage. In the control group, additional measures of surgical hemostasis were more often used, including hysterectomy (2.6% versus 1.9%) and relaparotomy (1.9% versus 1%). The median volume of blood loss was statistically lower in the study group (700 ml versus 800 ml). Nevertheless, it should be noted that there is a significant scatter in the data on the volume of blood loss: for example, in the control group the maximum blood loss was 10,000 ml, and in the study group - 4,500 ml. No serious complications were noted in either group.

Conclusion.

The study showed that the use of terlipressin can reduce the amount of blood loss in women with high risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, as well as reduce the number of hysterectomies and relaparotomies. It is necessary to continue the prospective part of the study with an increase in the randomized sample of patients.

Keywords

: obstetric hemorrhage, cesarean section, terlipressin

Obstetric hemorrhage is one of the main causes of maternal mortality in our country and throughout the world [1, 2]. To solve this problem, surgical methods of hemostasis during cesarean section (CS) are constantly being developed and improved to reduce the amount of blood loss. This is also the focus of research into new risk factors and the effectiveness of prophylactic use of tranexamic acid and various uterotonics [3, 4]. Research continues on the selection of safe and effective prophylactic doses of oxytocin and carbetocin not only in terms of correcting hemodynamic disorders, but also reducing the volume of intraoperative blood loss [5, 6]. Despite all the achievements and sometimes seeming successes, massive postpartum hemorrhage continues to be a global challenge to modern obstetrics, anesthesiology and intensive care. Therefore, the further search for means of prevention and treatment of atonic bleeding during CS surgery does not lose its relevance.

Purpose of the study.

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of terlipressin as a means of preventing the development of postpartum hemorrhage during cesarean section in high-risk pregnant women.

Patients and methods

The study design was developed and approved by the scientific committee of the Association of Obstetric Anesthesiologists and Resuscitators.

From February to December 2021, a multicenter omnidirectional cohort study TerliBleed was conducted, in which 5 medical centers took part: Krasnoyarsk Regional Clinical Center for Maternal and Child Health; Altai Regional Clinical Perinatal; Kuzbass Regional Children's Clinical Hospital; Voronezh City Clinical Emergency Hospital No. 8; Perinatal Center at City Clinical Hospital No. 24 of the Moscow Department of Health. Clinical data were collected and recorded prospectively and retrospectively. Consents were obtained from the ethical committees directly at each clinic where the study was conducted. The use of terlipressin did not contradict its instructions for medical use, according to which the indications for the use of the drug are: bleeding during surgical interventions on the abdominal and pelvic organs, uterine bleeding, including during childbirth and termination of pregnancy [7]. Our Voronezh colleagues also received a patent RU 2 709 819 C1 “Method of reducing blood loss during surgical delivery in high-risk postpartum women,” using terlipressin into the muscle tissue of the uterus [8]. The study involved 454 pregnant women with high risk factors for the development of bleeding, such as [9]: 1) impaired uterine contractility (atony, parity of birth more than 4);

2) multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios, large fetus;

3) uterine fibroids with a large node/nodes (>5 cm);

4) abnormal placentation (ICD O43, O44) – presentation, accreta, tight attachment of the placenta.

All women were delivered by CS. The operations were performed under both regional and general anesthesia. The volume of blood loss was assessed using the gravimetric method, by directly collecting blood into graduated containers, together with weighing blood-soaked napkins and surgical linen. The measured parameters were monitored three times: 24 hours before surgery, immediately after surgery, and the next day, 24 hours after CS.

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women with high risk factors for the development of massive and severe postpartum hemorrhage, who underwent CS surgery either planned or emergency, aged 18 to 49 years, parity and gestational age - without restrictions, no intolerance to terlipressin.

Exclusion criteria: the presence of cancer, tuberculosis, severe somatic pathology in the stage of decompensation, mental and mental disorders that impede productive contact, chronic alcoholism and drug addiction on the ASA scale of 4, 5, 6 degrees, the presence of contraindications to the use of the drug terlipressin.

The women were divided into 2 groups: a control group (group I), which included 351 patients who received standard bleeding prophylaxis in accordance with clinical recommendations [9], and a study group (group II), which consisted of 103 patients who received, in addition to standard prophylaxis, additional terlipressin (Remestip®, Ferring Company, Berlin, Germany) after fetal extraction and umbilical cord cutting. Terlipressin was injected into the incision site on the uterus - into the thickness of the myometrium, in a dose of up to 0.4 mg, diluted to 10 ml with a 0.9% sodium chloride solution [8].

To assess the preventive effect of the drug terlipressin, multiple primary endpoints were identified, which allow us to evaluate the drug in several important areas: the volume of postpartum blood loss; the need for additional methods of surgical hemostasis; the need for a hysterectomy; the need to administer second-line uterotonics; the need for relaparotomy.

Secondary endpoints were determined to comprehensively evaluate the safety of topical terlipressin in a specified population of pregnant women undergoing CS. In this regard, the assessment of the safety of the drug was also divided into several significant areas: acute respiratory failure (including indications for artificial pulmonary ventilation (ALV)); acute kidney injury; neurological complications; liver complications; multiple organ failure; side effects.

Statistical methods used for data analysis included: descriptive statistics methods (calculation of means, standard deviations for numerical indicators, absolute and relative frequencies for binary and categorical variables); Student's t-test to test the hypothesis about the difference between the means of two independent samples; c2 test and Fisher's exact test to test for differences in frequencies and frequency distributions of binary and categorical indicators. The significance level for accepting the statistical hypothesis about the significance of the difference was taken to be 0.05 (p < 0.05) with a power of criterion of 0.80. Data preparation for analysis and statistical processing were carried out using the Microsoft® EXCEL® 2010 Proofing Tools and STATISTICA 12 software packages, as well as standard libraries of the R software environment.

Research results and discussion

Carrying out a comparative assessment of anthropometric data, no statistically significant differences were obtained between groups I and II in age, height, weight and body mass index (BMI). However, the difference in the average gestational age was statistically significant (p = 0.007): in the control group, the average gestational age was 36 weeks, while in the study group it was a week longer (Table 1). In our opinion, this difference has no practical significance.

High parity is one of the significant risk factors for the development of postpartum hemorrhage. The influence of this risk factor is significantly increasing with the steady increase in the frequency of CS operations [10].

Groups I and II were comparable in the frequency of previous CS operations (p = 0.118) (Table 2). However, the presence of blood loss in previous births in the study group was more than 2 times higher compared to the control group: 8.7% versus 3.7%, if we calculate the frequencies for all patients in the group (p = 0.038). If we exclude from the calculations patients who have not had previous births, then the frequency ratio between the groups will be 12.9% (9/70) and 5.2% (13/262). Thus, the frequency of pathological blood loss during previous births in the study group is almost 2.5 times higher than in the control group, the difference is statistically significant (p = 0.023). These results from our analysis suggest that the majority of study participants used terlipressin in patients at higher risk of developing major postpartum hemorrhage.

An analysis of the frequency of occurrence of congenital hemostasis defects showed a calculated probability p close to the threshold of statistical significance. In the study group, the frequency was almost 5 times higher than in the control group (2.9% versus 0.6%, p = 0.054). The frequency of this pathology is generally very low in the population, and a much larger sample size is needed to make a more definite decision about the significance of the difference. However, this trend should be noted already in this sample (Fig. 1).

The frequency of various extragenital pathologies in group II was more than 2.5 times higher than that in the control group (45.63% versus 17.4%, respectively, p = 0.0001).

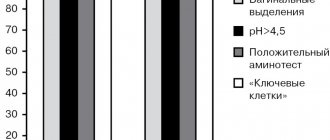

According to the results of the analysis of the frequency of occurrence of obstetric risk factors for the development of bleeding, statistically significant indicators were such indicators as multiple pregnancy, large fetus, placenta accreta, uterine fibroids >5 cm. In the control group, pathologies such as multiple pregnancy were more common (33.9% versus 21 .4%) and large fruit (20.5% versus 10.7%). On the other hand, in the study group, a more serious pathology, such as placenta accreta, was 2 times more common (15.5% versus 7.4%), which is more likely to increase the risk of massive bleeding that is life-threatening [10, 11].

The results of comparison of the incidence of obstetric risk factors between groups are presented in Fig. 2.

Based on the results obtained, we assume that in the study group, patients had a higher risk of developing postpartum hemorrhage. In this case, this is difficult to doubt, since the frequency of risk factors, especially such serious ones as placenta accreta, the presence of congenital defects of the hemostatic system and pathological blood loss during previous births are significant risk factors [10, 12]. It is possible that this fact from the anamnesis, as well as the presence of extragenital pathology and high risk factors, influenced the decision of our colleagues when selecting patients who were included in the study group. As a result, this led to the fact that in most centers, patients with obviously more significant risk factors were selected into the group of patients who received terlipressin. We are aware that this is one of the limitations of our study. But at this stage it was not possible for us, for ethical reasons, to make the study design more rigorous or to resort to various blinding options. In addition, in all cases, the decision to use terlipressin for prophylaxis was made by the anesthesiologist and critical care specialist together with the operating obstetrician-gynecologist based on a collegial, comprehensive assessment of the risk of bleeding.

Terlipressin is an effective drug in the treatment and prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding during operations on the liver and pelvic organs [13–15]. As for obstetrics, terlipressin has not been studied to date; there are only a few studies devoted to this issue [16]. In our opinion, the vasopressor effect of the drug is of undoubted interest [15], which can act on the vessels of the uterus, narrowing them, and thereby contribute to the development of primary hemostasis. Terlipressin (Ntriglycyl8 lysine vasopressin) is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin, a hormone of the posterior hypophysis. The pharmacological action of terlipressin is associated with its active metabolites, including lysine vasopressin, which predominantly acts on V1 receptors located in the smooth muscles of vessels of various sizes [15, 17]. This type of receptor has also been found on platelets: by acting on them, vasopressin and its analogues are able to increase their aggregation ability [18]. There are also studies showing the similarity in the structure of the molecules of terlipressin and oxytocin and the cross-effect of these drugs on the receptors of the same name, due to which the tone of the smooth muscles of the uterus can be further enhanced [19].

Assessing the studied parameters during CS surgery in this study, it should be noted that their frequency did not have statistically significant differences between groups I and II (Table 3). However, noteworthy is the more frequent implementation of various additional measures of surgical hemostasis in the control group. Thus, ligation of the uterine arteries in group I was carried out in 10.5% of cases, in group II - in 7.8%, application of compression sutures to the uterus - in 13.1 and 7.8%, respectively, the use of balloon tamponade of the uterus - in 2 .3% and 0% respectively. The most significant factor indicating massive and uncontrollable blood loss, such as hysterectomy, was more often noted in the control group - 9 (2.6%) cases than in the study group - 2 (1.9%), although it did not reach statistical significance. significance. Relaparotomy, when primary hemostasis was ineffective, was also more often observed in the control group (5 cases, 1.4%) than in group II (1 case, 1%) (Table 3).

In this case, one patient could use several additional methods of surgical hemostasis during CS surgery. Their comparison and frequency between groups is presented in Fig. 3.

Analyzing the frequency of occurrence of various methods of hemostasis during CS surgery, it can be noted that almost 2/3 of the patients in the study group did not use any additional measures to eliminate bleeding, while in the control group there were just over half of such patients. Also, one additional method of hemostasis used in the control group was performed in a third of the patients, whereas in the study group the proportion of such patients was smaller. Two or more methods of surgical hemostasis during CS were performed in 8.8% of patients in the study group, and in the control group, slightly more - in 10.9%. These differences add up to a picture suggesting that in the study group there were slightly fewer problems during CS surgery than in the control group. Further study of this issue is necessary to clarify whether this is the case and what factors, other than the use of terlipressin, could influence this frequency distribution.

The most important indicator of the effectiveness of preventing postpartum hemorrhage, of course, is the difference in the amount of blood loss between the study groups. When assessing these indicators, no statistically significant difference was achieved (Table 4).

The difference in the frequency of pathological and massive blood loss (>1000 ml) between groups I and II in this sample did not reach statistical significance.

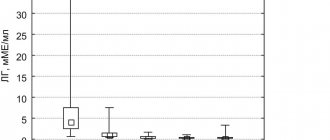

Due to the strongly left-skewed distribution and large outliers in the volume of blood loss, the mean values do not capture the differences between groups I and II (Table 5), however, the medians in the overall sample differ and the Mann–Whitney test indicates a statistically significant difference in the distribution of blood loss volume between groups ( p = 0.002). The distribution of blood loss volume in our study is clearly visible in the diagram (Fig. 4). One can note a significant scatter of data and maximum indicators in the control group. Thus, in the control group the maximum blood loss was 10,000 ml, and in the study group it was two times less - 4500 ml.

Analyzing these indicators, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions about the effectiveness of terlipressin in the comparison groups in terms of preventing pathological blood loss. However, when assessing the median and interquartile range of blood loss volume, lower blood loss rates can be noted in the study group using terlipressin. It can be assumed that if the same risk factors and underlying pathology are identified, these indicators may change.

The second, no less important, goal of the study was a comprehensive assessment of the safety of the use of the drug terlipressin in obstetric practice.

Local use of terlipressin was chosen to reduce the systemic exposure of the drug to the body, thereby minimizing its adverse effects. Considering that terlipressin is a powerful vasopressor, when administered intravenously, it causes systemic contraction of vascular smooth muscle and internal organs, which leads to an increase in total peripheral vascular resistance [8]. Clinically, this can manifest itself as increased blood pressure, tachycardia or bradycardia, and headache. Clinical cases with the development of skin necrosis during the use of terlipressin have also been described [20]. All these side effects have been described in the literature with intravenous administration of the drug. The instructions for use of the drug allow its local, steam and/or intracervical use in a dose of 4 ml (0.4 mg) with dilution to 10 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution [7].

Almost all of the complications noted in the study have a low frequency of occurrence in the population, therefore, in this sample of several hundred patients, most complications did not appear at all, and the few that were registered occurred in isolated cases, which did not allow for an adequate comparative analysis of frequencies complications between groups (Table 6).

In the control group, 7 patients had an increase in the activity of liver enzymes and 3 had a decrease in diuresis of <0.5 ml/kg/h, while in the study group these complications were not recorded, but the difference was statistically insignificant. The remaining complications were either absent in both groups or had comparable relative frequencies.

I would like to note the absence of severe complications in the form of deaths and severe organ damage in both groups. Also, in the group with terlipressin, there were no complications associated with local application of the drug into the myometrium. Our results coincide with the data of a number of studies devoted to the use of terlipressin in obstetrics and gynecology [16, 21, 22].

Conclusion

Carrying out a comparative statistical analysis of the frequency of risk factors, obstetric history and comorbidity of the compared groups, we found that in the study group using terlipressin, patients were more severe and at risk of developing pathological and massive bleeding. This is presumably due to patient selection principles, as some centers have used terlipressin in patients at highest risk of bleeding as an adjunctive method of prevention, and in some cases to treat bleeding in high-risk patients, after which the patients were enrolled in the study. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to continue to conduct additional prospective studies with more stringent patient selection and sufficient sample size and randomization of patients into groups. A matched-pair sampling study may be useful for this purpose.

However, it should be noted that, despite the above, the use of terlipressin made it possible to statistically significantly reduce the volume of blood loss and the frequency of additional methods of surgical hemostasis, such as ligation of the uterine arteries, compression sutures on the uterus, and balloon tamponade of the uterus. Of particular importance is that the use of terlipressin has reduced the number of hysterectomies as the last method of surgical control of bleeding and the number of relaparotomies.

The results of our study showed that when terlipressin was applied topically, there were no systemic or side effects or negative manifestations of the drug.

Funding information There was no funding for this work. Financial support

No financial support has been provided for this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

During the study, informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Informed consent

In carrying out the study, written informed consent was obtained from all patients

Literature

1. Hawkins SS, Ghiani M, Harper S, Baum CF, Kaufman JS.

Impact of State-Level Changes on Maternal Mortality: A Population-Based, Quasi-Experimental Study. Am J Prev Med. 2021 Feb;58(2):165-174. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.09.012 2. Konoplyannikov AG, Mikhaleva LM, Olenev AS, Kudryavtseva YU, Songolova EN, Gracheva NA, et al. Analysis of the structure of maternal mortality. Issues of gynecology, obstetrics and perinatology. 2020;19(3):133-138. DOI: 10.20953/ 1726-1678-2020-3-133-138

3. Franchini M, Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Bergamini V, Presti F, Marano G, et al. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid for prevention of obstetric haemorrhage: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Transfus. 2021 Jul; 16(4):329-337. DOI: 10.2450/2018.0026-18

4. Onwochei DN, Owolabi A, Singh PM, Monks DT. Carbetocin compared with oxytocin in non-elective Caesarean delivery: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2020 Nov;67(11):1524-1534 DOI: 10.1007/s12630-020-01779-1 (In English).

5. Degtyarev EN, Shifman EM, Tikhova GP, Kulikov AV. The effect of oxytocin dose on changes in the ST segment, arterial hypotension and the amount of blood loss in parturient women of different age groups during cesarean section. Bulletin of Intensive Care named after. A.I. Saltanova. 2018;3:77-87. DOI: 10.21320/ 1818-474X-2018-3-77-86

6. Degtyarev EH, Shifman EM, Tikhova GP, Kulikov AV, Zhukovets IV. The effect of oxytocin dose on the volume of intraoperative blood loss during cesarean section. Issues of gynecology, obstetrics and perinatology. 2018;17(6):51-56. DOI: 10.20953/1726-1678-2018-6-51-56

7. Instructions for medical use of the drug Terlipressin, Ferring-Lechiva A.S. Address: https://grls.rosminzdrav.ru/Grls_View_v2. aspx?routingGuid=b101de51-90de-409b-9f78-09f6aa529149&t=

8. Patent for intrauterine administration of Remestip. Address: https://new.fips.ru/ registers-doc-view/fips_servlet?DB=RUPAT&DocNumber=0002709819&TypeFile=html

9. Shifman EM, Kulikov AV, Ronenson AM, Abazova IS, Adamyan LV, Andreeva MD, et al. Prevention, management algorithm, anesthesia and intensive care for postpartum hemorrhage. Clinical recommendations. Bulletin of Intensive Care named after. A.I. Saltanova. 2019;3:9-33. DOI: 10.21320/ 1818-474X-2019-3-9-33

10. Kong CW, To WWK. Risk factors for severe postpartum haemorrhage during caesarean section for placenta praevia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021 May;40(4): 479-484. DOI: 10.1080/01443615.2019.1631769

11. Davydov AI, Strizhakov AN, Novruzova NH. Complications of surgical hysteroscopy: prevention and treatment. Issues of gynecology, obstetrics and perinatology. 2016;15(6):52-60. DOI: 10.20953/1726-1678-2016-6-52-60

12. Davey MA, Flood M, Pollock W, Cullinane F, McDonald S. Risk factors for severe postpartum haemorrhage: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol. 2020 Aug;60(4):522-532. DOI: 10.1111/ajo.13099

13. Zhou X, Tripathi D, Song T, Shao L, Han B, Zhu J, et al. Terlipressin for the treatment of acute variceal bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Nov;97(48):e13437. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013437

14. Abbas MS, Mohamed KS, Ibraheim OA, Taha AM, Ibraheem TM, Fadel BA, et al. Effects of terlipressin infusion on blood loss and transfusion needs during liver resection: A randomized trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021 Jan;63(1):34-39. DOI: 10.1111/aas.13226

15. Morelli A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, Lange M, Orecchioni A, Cecchini V, et al. Continuous terlipressin versus vasopressin infusion in septic shock (TERLIVAP)

16. Aleksandrovich YuS, Rostovtsev AV, Kononova ES, Pshenisnov KV, Akimenko TI. Efficacy of low doses of terlipressin for the prevention of intraoperative blood loss in obstetrics. Bulletin of anesthesiology and resuscitation. 2020;17(4):78-84. DOI: 10.21292/2078-5658-2020-17-4-78-84

17. Manning M, Stoev S, Chini B, Durroux T, Mouillac B, Guillon G. Peptide and non-peptide agonists and antagonists for the vasopressin and oxytocin V1a, V1b, V2 and OT receptors: research tools and potential therapeutic agents. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:473-512. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00437-8

18. Inaba K, Umeda Y, Yamane Y, Urakami M, Inada M. Characterization of human platelet vasopressin receptor and the relationship between vasopressin-induced platelet aggregation and vasopressin binding to platelets. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1988 Oct;29(4):377-86. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb02886.x

19. Manning M, Misicka A, Olma A, Bankowski K, Stoev S, Chini B, et al. Oxytocin and vasopressin agonists and antagonists as research tools and potential therapeutics. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012 Apr;24(4):609-28. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012. 02303.x

20. Busta Nistal MR, Mora Cuadrado N, Fernández Salazar L. Ischemic skin necrosis secondary to the use of terlipressin. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021 Dec 3. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2020.7467/2020

21. Brünnler T, Mandraka F, Langgartner U. Terlipressin: clinical use, rational dosing, comparison of the effectiveness of different administration regimens. Health of Ukraine. 2010;2(13):3.

22. Rundqvist E, Allen D, Larsson G. Comparison between lysine vasopressin and a long-acting analogue (N alpha-triglycyl-lysine vasopressin) used as local hemostatic agents for conization. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67(4):301-5

Information about co-authors:

Shifman Efim Munevich, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimatology, Moscow Regional Research Clinical Institute named after. M.F. Vladimirsky; President of the Association of Obstetric Anesthesiologists and Resuscitators; Honored Doctor of the Republic of Karelia; expert in anesthesiology and resuscitation of the Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare Address: 129110, Moscow, st. Shchepkina, 61/2 Phone: (495) 6816000 Email ORCID: 0000000261138498

Belinina Antonina Anatolyevna, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Deputy Chief Physician of the Altai Regional Clinical Perinatal Center Address: 656047, Barnaul, st. Fomina, 154 Phone: (385) 2569381 Email ORCID: 000000021038366

Rostovtsev Andrey Viktorovich, head of the department of anesthesiology of intensive care, Voronezh City Clinical Emergency Hospital No. 8; Chief freelance anesthesiologist-resuscitator in the field of “Obstetrics and Gynecology” of the Voronezh region Address: 394008, Voronezh, st. Rostovskaya, 90 Phone: (920) 2116116 Email ORCID: 000000030375752X

Artymuk Natalya Vladimirovna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after. prof. G.A. Ushakova Kemerovo State Medical University Address: 650056, Kemerovo, st. Voroshilova, 22a Phone: (960) 9233355 Email ORCID: 0000000170146492

Olenev Anton Sergeevich, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Deputy Chief Physician for Medical Affairs, Head of the Perinatal Branch, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with a course of Perinatology at the RUDN Medical Institute, Chief Freelance Specialist in Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Moscow Department of Health Address: 127287, Moscow, 4th Vyatsky lane, 39 Phone: (495) 6134509 Email ORCID: 0000000196326731

Alexandrovich Yuri Stanislavovich, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Anesthesiology, Reanimatology and Emergency Pediatrics, Faculty of Postgraduate and Additional Professional Education, St. Petersburg State Pediatric Medical University Address: 194100, St. Petersburg, st. Litovskaya, 2A Phone: (921) 5898126 Email ORCID 0000000221314813

Tskhai Vitaly Borisovich, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Perinatology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University. prof. V.F. VoinoYasenetsky; Head of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Couple Health Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency of Russia Address: 660022, Krasnoyarsk, st. P. Zheleznyaka, 1 Phone: (391) 2653584 Email ORCID: 000000032283884

Novikova Oksana Nikolaevna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after. prof. G.A. Ushakova Kemerovo State Medical University Address: 650059, Kemerovo, st. Voroshilova, 22A Phone: (384) 2533016 Email ORCID 0000000155701988

Management of patients with major obstetric hemorrhage before peripartum hysterectomy and outcomes in nine European countries

Purpose

This study was to compare management strategies for obstetric hemorrhage leading to hysterectomy in 9 European INOSS participating countries and to describe maternal and neonatal outcomes after peripartum hysterectomy.

Material and methods.

We pooled data from nine national or multiregional obstetric studies conducted in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Sweden and the UK between 2004 and 2021. Hysterectomies were performed between 22 gestational weeks and 48 hours postpartum. The incidence of maternal mortality, complications after hysterectomy and adverse neonatal outcomes (stillbirth or neonatal mortality) were taken into account.

Results.

The study included 1302 women. Uterotonic use was lowest in Slovakia (48/73, 66%) and highest in Denmark (25/27, 93%), intrauterine balloon use was lowest in Slovakia (1/72.1%) and highest in Denmark (11/27, 41%), and interventional radiology ranged from 0/27 in Denmark and Slovakia to 11/59 (79%) in Belgium. In women with placenta accreta, uterotonic use was lowest in Finland (5/16, 31%) and highest in the UK (84/103, 82%), intrauterine balloon use ranged from 0/14 in Belgium and Slovakia to 29/103 (28%) in the UK. Interventional radiology was lowest in Denmark (0/16) and highest in Finland (9/15, 60%). Maternal mortality was 14/1226 (1%), the most common complications were hematological (95/1202, 8%) and respiratory (81/1101, 7%). Complications in newborns were observed in 79 (6%).

Conclusion.

Management of obstetric hemorrhage in women who ultimately underwent peripartum hysterectomy varied widely across the nine European countries. This potentially life-saving surgery is associated with significant adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Kallianidis AF, Maraschini A, Danis J et al. INOSS (the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems).

Management of major obstetric hemorrhage prior to peripartum hysterectomy and outcomes across nine European countries.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021 Mar 14. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14113. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands

Use of the drug Glipressin

Dissolve the powder by introducing the supplied solvent into the bottle. First, 1–2 mg of Glypressin (1–2 bottles) is administered intravenously slowly. Maintenance dose - 1 mg (1 bottle) every 4-6 hours. The daily dose of Glypressin is usually 120-150 mcg/kg body weight; for adults weighing 70 kg - 8–9 mg/day, administered at 4-hour intervals. Further dilution of the drug can be done by adding 0.9% sodium chloride solution to 10 ml. Glipressin is used only with constant cardiac monitoring (blood pressure, heart rate, fluid balance) in an intensive care unit. The drug can be used in the prehospital stage as first emergency aid for suspected bleeding. When using the drug, constant monitoring is necessary for signs of hypovolemia. If necessary, drug therapy can last 2–3 days.

Side effects of the drug Glypressin

pallor of the skin, moderate or significant (with hypertension (arterial hypertension)) increase in blood pressure, arrhythmia, bradycardia, as well as the development of acute coronary insufficiency. In some cases, headache and local necrosis were noted. Terlipressin may increase gastrointestinal motility due to its stimulating effect on smooth muscles, which is manifested by abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea. In some cases, bronchospasm can cause shortness of breath. Contraction of the uterine muscles can cause circulatory problems in the endometrium and myometrium. Isolated cases of hyponatremia and hypokalemia are possible, especially if the water balance is initially disturbed.

Special instructions for the use of the drug Glipressin

Glypressin is used with caution, subject to monitoring, for the following conditions and diseases: asthma, hypertension (arterial hypertension), damage to the heart and blood vessels (generalized atherosclerosis, heart disease, coronary insufficiency, arrhythmia), renal failure. During pregnancy and breastfeeding . The use of Glipressin is contraindicated due to possible malformation of fetal organs and spontaneous abortion. During the period of use of the drug, stop breastfeeding. Children . There is no experience with the use of Glipressin in children, so the drug should not be used in pediatric practice. Does not affect reaction speed when driving vehicles or operating machinery .

Drug interactions Remestip

The vasoconstrictor effect and stimulating effect on myometrial tone are enhanced when combined with oxytocin and methylergometrine. Remestip potentiates the effect of non-selective β-adrenergic receptor blockers in reducing pressure in the portal vein system. Combined use with drugs that reduce heart rate may cause severe bradycardia. The drug should not be mixed in the same syringe with other medications. Use only recommended solvents.