While carrying a child, the female body needs a large amount of useful substances that participate in the processes that occur during pregnancy and ensure the growth and development of the fetus. One of the most important microelements is iron. Unfortunately, 40% of pregnant women develop iron deficiency - this condition is called iron deficiency anemia. It is caused by a decrease in the level of hemoglobin, a complex iron-containing protein that binds oxygen and delivers it to tissues and organs. As a result of anemia, cells do not receive enough oxygen, which is dangerous for the health of both the woman and the child.

Why does iron deficiency occur during pregnancy, what are its signs and consequences?

Risk group for anemia in pregnant women:

- Pregnancy in adolescence.

- Pregnancy and lactation during the previous 3 years, many births (more than 3 with a short interval).

- Excessive menstrual blood loss (monthly blood loss more than 100 ml).

- Gynecological diseases, especially uterine fibroids and endometrial diseases, inflammatory diseases of the pelvic organs.

- Diets low in animal protein (vegetarianism).

- Regular blood donation.

- Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Low socio-economic status.

- Obesity.

At the same time, WHO recommends that all menstruating women be considered at risk, provided that the prevalence of anemia in non-pregnant women in the region exceeds 20%.

Too much hemoglobin is harmful

It is very important that the hemoglobin level during pregnancy is normal. Excess hemoglobin is just as harmful as its deficiency.

Not only too little, but also too much hemoglobin has been found to be associated with too low a newborn's birth weight. Excess hemoglobin at 13-19 weeks of pregnancy is also associated with a risk of fetal death, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, maternal hypertension (high blood pressure) and all related complications.

Excess free iron in tissue is associated with the formation of free radicals and oxidative stress, which can damage the placenta. Damage to the placenta, in turn, can cause premature birth, there is a greater risk that the fetus will develop more slowly and the unborn child will have a physical disability, mental retardation or emotional disturbance.

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT

[contact-form-7 id=”296″ title=”Untitled”]

Abortion and contraception clinic in St. Petersburg - department of the medical gynecological association "Diana"

Make an appointment, tests or ultrasound via the contact form or by calling +8 (812) 62-962-77. We work seven days a week from 09:00 to 21:00.

We are located in the Krasnogvardeisky district, next to the Novocherkasskaya, Ploshchad Alexander Nevsky and Ladozhskaya metro stations.

The cost of a medical abortion in our clinic is 3,300 rubles. The price includes all pills, an examination by a gynecologist and an ultrasound to determine the timing of pregnancy.

Prevention of anemia during pregnancy:

Women at risk with normal clinical blood test values are advised to take the following preventive measures before pregnancy.

- Ensuring an adequate interval between births (2-4 years).

- Regulation of the menstrual cycle and reduction of blood loss during menstruation through the use of hormonal contraceptives.

- Treatment of acute and compensation of chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

- A balanced diet with the obligatory inclusion of animal protein.

- Preventive administration of iron supplements.

- Observation by a hematologist.

HEMATOGEN AS A SOURCE OF IRON IN THE BODY

This product has been used for decades to enrich the diet with iron in people at risk. When choosing this nutritional supplement, you should pay attention to its composition. Initially, hematogen was made exclusively from albumin - processed cattle blood. However, over time, many manufacturers, trying to improve the taste of the product, began to make changes to the classic recipe. This has led to the emergence of a large number of hematogen analogues, which include fillers such as nuts, honey, chocolate, seeds, etc. Such components increase the calorie content of the hematogen and the risk of developing allergies and often interfere with the absorption of iron. Hematogens that do not contain foreign ingredients include ferrohematogen.

The danger of anemia during pregnancy:

The danger of anemia during pregnancy is that it leads to complications during pregnancy, childbirth and after childbirth. This is a violation of fetal development, toxicosis, premature birth, premature placental abruption, untimely rupture of water, weakness of labor, bleeding, inflammatory complications, decreased quantity and quality of milk. With anemia during pregnancy, premature birth and placental insufficiency are 3-4 times more likely, labor weakness and preeclampsia are 2-3 times more likely, and infectious and inflammatory complications and bleeding after childbirth are 2 times more likely. Iron deficiency affects both the intrauterine development of the fetus, especially the brain, and the further development of the child, who is born with iron deficiency and anemia. These children have reduced physical strength, endurance, and mental capabilities; the function of the immune and nervous systems is impaired.

When is anemia diagnosed?

The normal level of hemoglobin in the blood according to different values is from 110 to 144 g/l. The lower the indicator, the more severe the form of the disease:

- a decrease in hemoglobin below a minimum value of 110 to 90 g/l is considered mild anemia;

- 89–70/l - average level;

- below 70 g/l - severe anemia.

Anemia is one of the most common problems that occurs during pregnancy, its frequency reaches 58%. A slight decrease in hemoglobin levels during pregnancy is possible (normally by the 32nd week of pregnancy), due to the fact that the volume of circulating plasma in a woman’s body increases by 50%, and the number of red blood cells increases by only 18–20%.

Treatment of anemia:

Treatment of anemia consists of proper nutrition and taking iron supplements with vitamins for a long time. Your doctor will prescribe medications for you, but you need to know how to eat properly during pregnancy.

The female body needs 1.5-1.7 mg of iron per day, during pregnancy - up to 6-7 mg. Throughout pregnancy you need 2000 mg of iron. With normal nutrition during pregnancy, a woman receives 700-800 mg and another 400-500 mg is consumed from the depot.

What if the iron supply in the depot is reduced (ferritin below 30 mcg/l)? 12 - 15% of women in the reproductive period of the Russian Federation suffer from iron deficiency anemia, and 60% from hidden iron deficiency. Therefore, it is so necessary to create an iron reserve before pregnancy. How often do women say at a doctor’s appointment: “But my hemoglobin is always low and I live.” But this is dangerous for pregnancy, as it poses a risk not only for the mother, but also for her child. It is right for such women to be examined and treated before pregnancy.

RISK FACTORS

WHO statistics indicate that the possibility of developing iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy does not directly depend on either the financial situation or the social status of the woman. Domestic data demonstrate a gradual increase in the number of cases of this pathology. This is due to the fact that even a normal pregnancy predisposes to the development of iron deficiency anemia, since it is during this period that active consumption of iron occurs. It is necessary for the formation of the placenta and the circulatory system of the fetus. At a later date, the microelement is deposited in the fetoplacental complex of the unborn child: the formation of this reserve is also ensured by the body of the pregnant woman. Iron continues to be actively consumed later - during childbirth (due to blood loss) and during lactation.

Nutrition for anemia:

It is important to remember that iron, which is absorbed by the human body, is found in the following foods: liver (the champion in iron content), meat, fish, eggs. Apples, pomegranates and other fruits and vegetables contain small amounts of iron that are not absorbed. But vegetables and fruits are necessary, as they contain vitamins, microelements and fiber necessary for the absorption of foods containing iron.

The daily intake of meat, liver, or fish is at least 200 grams, as well as 1 egg. Only 2.5 mg of iron per day is absorbed from food (6-7 mg is needed during pregnancy), 15-20 times more from iron supplement tablets, so all pregnant women need a preventive dose of iron of 60 mg per day, which is contained in all vitamin and mineral supplements. complexes for pregnant women. Pregnant women with hidden iron deficiency or clinical anemia need a therapeutic dose of 100-200 mg. You need to know that tea, coffee, legumes, grains, rice, and dairy products significantly reduce the absorption of iron from foods and medications. Products containing vitamin C accelerate the absorption of iron entering the gastrointestinal tract.

Proper nutrition, timely prevention and treatment guarantee a reduction in complications for mother and child.

Iron deficiency conditions and iron deficiency anemia in women of childbearing age

Iron is one of the most important elements in the human body and is part of many substrates and enzymes responsible for the transport of oxygen to cells, the functioning of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, redox cellular reactions, antioxidant protection, the functioning of the nervous and immune systems, etc.

The average adult human body contains about 3–4 g of iron (Fe) (about 40 mg Fe/kg body weight in women and about 50 mg Fe/kg body weight in men). Most of the iron (60%, or more than 2 g) is contained in hemoglobin (Hb), about 9% of iron is in myoglobin, about 1% is contained in heme and non-heme enzymes. 25–30% of iron is in the depot, being associated mainly with the protein ferritin, as well as with hemosiderin [1, 2] (Table 1).

The exclusive role of iron and its significant amount in the body determine the high daily requirement for iron, which depends on age and gender.

The highest need for iron is observed in children of the first years of life (about 1 mg per day), which is associated with high rates of growth and development; during puberty, especially in girls due to the onset of menstruation (about 2 mg/day); in women of childbearing age who have monthly menstrual iron losses (about 2.5 mg/day), in pregnant women, especially in the third trimester of pregnancy (up to 6 mg/day), which is associated with the growth and formation of the fetus and an increase in the number of red blood cells in the mother , in lactating women (about 3 mg/day) [3]. The lowest requirement for iron is typical for adult men - about 1 mg/day, which is comparable to the need for a child of the first year of life [4, 5]. The higher the daily requirement for iron, the more likely it is to develop iron deficiency (ID) and its most severe stage - iron deficiency anemia (IDA).

The nature of the diet is of great importance in providing the body with iron. Many foods of plant origin and mushrooms contain large amounts of iron, but it is presented in the form of salts with low bioavailability, due to which only a small percentage (1–7%) is absorbed in the intestines. In products of animal origin, iron is presented in the form of heme, which ensures its high absorption capacity (bioavailability 25–30%) [5]. Therefore, to provide the body with iron, it is necessary to consume meat, liver and other animal products. Considering that many women of childbearing age are addicted to various “diets” low in animal products, their risk of developing ID increases.

Epidemiology of iron deficiency

Iron deficiency is defined as a deficiency in the total amount of iron caused by a discrepancy between the body's increased needs for iron and its intake or loss, leading to a negative balance [2]. According to World Health Organization estimates (2002), ID of varying severity affects about 4 billion people, which is more than 60% of the world's population. Of these, IDA accounts for almost 2 billion, which makes IDA the most common disease in the world and the most common among anemias (90%) [6].

The highest rates of ID are typical for these risk groups. Thus, ID is registered in more than 51% of women of childbearing age, which is associated with monthly blood loss and pregnancy.

Without external iron supply, most women develop ID during pregnancy [7]. A study by S. Kagamimori et al., conducted in 1998, showed that 78% of Japanese schoolgirls had ID of varying severity already 3 years after the onset of menstruation [8].

The prevalence of ID depends on the socio-economic development of society. In developed countries, the incidence of ID is several times lower than in developing countries. ID, including IDA, is observed in almost 60% of pregnant women in developing countries, while in developed countries this figure does not exceed 14–15%. Among women of childbearing age, these figures are about 50% and 11%, respectively [9, 10].

Iron deficiency in a pregnant woman can develop at any stage, but most often it is recorded in the third trimester of pregnancy, since the need for iron during this period is highest. Moreover, according to some authors, ID of varying severity by the end of pregnancy is observed in almost all pregnant women. The risk of ID increases with multiple pregnancies and with short intervals between them.

Understanding the prevalence of ID and IDA in the Russian Federation is difficult due to low detection, especially of latent ID. According to the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, approximately 45% of completed pregnancies have IDA, and according to a number of independent studies, this figure is close to 60% [11–13].

Features of iron metabolism, etiology and pathogenesis of iron deficiency in pregnant women

HDD is always secondary. In principle, two groups of conditions leading to ID can be distinguished. The first group includes physiological and pathological conditions associated with an increased need for iron. These include periods of increased growth in children, pregnancy, breastfeeding, acute and chronic blood loss, etc. The second group of reasons are conditions associated with insufficient intake of iron into the body: a diet poor in “heme” iron, fasting, impaired intestinal absorption and so on.

Women of childbearing age are at risk for developing iron deficiency because they have higher iron requirements. Many of them have chronic latent iron deficiency, which, as a rule, remains undiagnosed for a long time, since there are no pronounced clinical symptoms, and the body is well adapted to it.

Another important problem of iron deficiency in young women is dietary habits: addiction to “diets”, exclusion or significant restriction of basic iron-containing foods in the diet, excessive consumption of foods that inhibit iron absorption (chocolate, tea, coffee, cereals and others).

Therefore, by the time pregnancy occurs, up to 50–60% of women do not have sufficient iron reserves not only to ensure the development of the fetus, but even for their own increased needs. But even with sufficient reserves of iron, a pregnant woman’s depot is depleted approximately by the beginning of the second trimester of pregnancy [2, 11–13].

During pregnancy, iron is intensively spent on the development and growth of the fetus (up to 500 mg of iron), increasing the mass of the pregnant erythrocytes (up to 700 mg of iron), and the formation of the uteroplacental complex (up to 150 mg of iron). Taking into account individual daily losses, a normal pregnancy requires 1000–1500 mg of iron [2, 11, 12].

In the first trimester, the source of iron for a pregnant woman is mainly the depot. The absorption of iron in the intestines during this period changes little, compensating only for the woman’s daily needs, and at the beginning of the second trimester the iron depot is depleted. Further provision of ever-increasing iron requirements can only be met by absorption in the intestine. The intensity of iron absorption in a pregnant woman gradually increases starting from the second trimester, sometimes reaching ten times the level in a non-pregnant woman. Thus, a pregnant woman’s diet should contain a large amount of readily available iron, taking into account the new high abilities for its absorption [2].

Childbirth dramatically reduces a woman's need for iron. However, childbirth itself, taking into account blood loss, can lead to a loss of 100–200 mg of iron. Lactation that follows also requires about 0.3 mg of iron per day, which increases the daily iron requirement of a nursing mother to 1.3–1.5 mg per day. Resuming menstruation after some time will lead to an increase in daily requirements to 2.5–3.0 mg [2].

Considering the above, it can be argued that almost all women during pregnancy and breastfeeding experience iron deficiency of varying severity.

Diagnosis of IDA and ID

Diagnosing iron deficiency anemia is usually not difficult. However, detection of iron deficiency before the stage of IDA is usually poorly done.

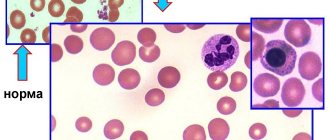

In principle, two stages of iron deficiency can be distinguished [14]. Latent iron deficiency is characterized by a decrease in iron in the depot (ferritin level decreases); then a deficiency of transport iron occurs (the percentage of transferrin saturation with iron decreases, the iron-binding capacity of blood serum increases). The depot is completely depleted, and erythropoiesis acquires the character of “iron deficiency” (the number of hypochromic erythrocytes and the concentration of protoporphyrin in erythrocytes increases). At all these stages, peripheral blood counts remain normal, which greatly complicates the diagnosis of iron deficiency. Only in the final stages does IDA develop (clinically pronounced iron deficiency). Thus, the identified cases of IDA represent only the “tip of the iceberg” of the number of cases of iron deficiency.

Diagnosis of ID and IDA should be based primarily on laboratory parameters. The most informative indicators for identifying IDA and ID are the hemoglobin level, the number of red blood cells and capillary blood hematocrit, the level of serum ferritin, the percentage (coefficient) of transferrin saturation with iron, the percentage of hypochromic red blood cells. Less reliable indicators are the level of serum iron and the total iron-binding capacity of the serum [1].

Hemoglobin, red blood cells, hematocrit

The level of hemoglobin in peripheral blood is the main indicator for identifying anemia and assessing its severity. The lower limit of hemoglobin level in women of childbearing age is considered to be 120 g/l, for pregnant women in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy - 110 g/l, in the second trimester - 105 g/l. Thus, a hemoglobin value below 120 g/L for a non-pregnant woman and below 105 g/L for a pregnant woman indicates the presence of anemia [15].

Depending on the degree of decrease in hemoglobin, anemia in pregnant women is divided into three degrees of severity [16]:

- light - 110–91 g/l;

- medium-heavy - 90–81 g/l;

- heavy - below 80 g/l.

A clinically significant criterion for assessing postpartum anemia is considered to be a hemoglobin level below <100 g/L. The minimum hemoglobin level after birth is reached approximately 48 hours due to the redistribution of blood plasma. Typically, such values are a consequence of post-hemorrhagic anemia and, in some cases, iron deficiency anemia present before birth. In addition, the level of hemoglobin before birth is important [15].

The number of red blood cells not only allows you to assess the presence of anemia, but also calculate the color index. The color index is calculated using the formula: (hemoglobin index (g/l) × 3)/the first three digits of the number of red blood cells. Color index values below 0.85 indicate the hypochromic nature of anemia, that is, they indicate its iron deficiency genesis. The total volume of all red blood cells is estimated by the hematocrit value.

Serum ferritin is the most important indicator for assessing iron stores in the body. Normally, its concentration is about 60–140 μg/l, but not less than 40 μg/l. Values below 15 µg/l indicate the presence of iron deficiency, even if other indicators are normal. In pregnant women, in 90% of cases, a decrease in ferritin levels below 30 μg/l already indicates the presence of iron deficiency [1, 15].

Low ferritin values in combination with decreased red blood cell or hemoglobin levels indicate iron deficiency anemia. It should be taken into account that during an inflammatory response, the determined serum ferritin level may be “falsely normal” or “falsely elevated”, since ferritin and acute phase proteins react in the same way. For this reason, it is recommended to determine the level of C-reactive protein in parallel with the determination of ferritin levels. For the same reason, ferritin levels are uninformative within 6 weeks after birth [15].

The percentage of transferrin saturation with iron allows us to assess the state of the iron transport pool. Normally, this figure ranges from 30–45%. With iron deficiency, the percentage of transferrin saturation is always below 20%.

Percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes and protoporphyrin

Normally, the number of hypochromic erythrocytes in peripheral blood, i.e. erythrocytes with a large amount of protoporphyrin, is about 2.5%, but not more than 5%. Their number increases with iron deficiency erythropoiesis. An increase in the proportion of hypochromic erythrocytes to 10% is possible with absolute and functional iron deficiency, more than 10% - only with absolute deficiency [2].

The more pronounced the iron deficiency, the higher the erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels. Normally, these values are about 0.3–0.9 μmol/L; in iron deficiency erythropoiesis, they are below 0.28 μmol/L [2].

Consequences of IDA and ID in pregnant women

The presence of IDA and ID during pregnancy and childbirth is associated with severe consequences for both the mother and the fetus. The risk of maternal and fetal death, premature birth, intrauterine growth retardation, impaired placental development, and decreased iron reserves in the newborn’s body increases [12, 15].

Considering the importance of iron for the development and functioning of the nervous system of a young child, its deficiency in the first months of life can lead to irreversible impairments in mental and psychomotor development [17].

In non-pregnant and pregnant women, iron and IDA deficiency can manifest as chronic fatigue, decreased performance, impaired concentration and decreased sense of danger, which can lead to injury and accidental death [18–20]. ID also leads to the development of immunodeficiency and increased susceptibility to infections [2].

Prevention and treatment of iron deficiency

The main method of preventing iron deficiency conditions is good nutrition and a rational daily routine for pregnant and lactating women. The diet should include both foods high in iron and foods containing iron supplements, which include copper, zinc, folic acid, vitamin B12, succinic acid, and ascorbic acid. According to the modern theory of iron absorption from food, heme iron, that is, iron contained in foods of animal origin, has maximum bioavailability. The richest sources of iron are rabbit meat, beef, and offal (tongue, liver). Plant foods, as well as milk and fish, contain iron in non-heme form, which is low bioavailable. It is necessary to take into account that products of plant origin may contain factors that inhibit intestinal ferrosorption. These factors include: soy protein, tannin, calcium, phytates, phosphates, dietary fiber, polyphenols. In turn, substances such as lactic acid, ascorbic acid, etc. can promote ferrosorption (Table 2).

A complete and balanced diet cannot eliminate iron deficiency, but only serves as a condition for maintaining the body’s physiological need for this element. In conditions of increasing need or increased loss of iron by the body, it is impossible to compensate for iron deficiency with dietary correction.

Along with dietary correction of ID in pregnant and nursing mothers, there is drug prevention of this condition. Correction can be routine (iron supplements are prescribed to all pregnant and nursing mothers - more often used in developing countries, since the traditional diet there does not provide women with enough iron, and some infections increase iron loss) or be selective (depending on the degree of iron deficiency). For prevention, it is possible to use the so-called “small doses” method. Most researchers agree that approximately 50–70 mg of iron per day is sufficient for effective prevention. This can be achieved by taking vitamin and mineral complexes. Based on clinical and laboratory data, the administration of iron supplements is indicated when SF decreases to less than 20 mcg/l. It must be remembered that taking iron supplements during pregnancy may be contraindicated in patients suffering from hereditary hemochromatosis, hereditary hemolytic anemia and other conditions accompanied by a pathological increase in serum iron levels and its increased deposition in tissues [2, 11–13].

Iron iron therapy always pursues two main goals: eliminating iron deficiency and restoring its reserves in the body.

To achieve maximum effect in the treatment of IDA, they rely on a number of basic principles (L.I. Idelson, 1981) [21].

- Reimbursement for railway transportation without medications is impossible.

- When treating IDA, preference is given to oral medications. These drugs have a number of advantages, the main one being the absence of serious side effects, including taking oral iron supplements does not lead to the development of hemosiderosis. At the same time, their effectiveness is comparable to that of parenteral drugs.

- Treatment does not stop after normalization of hemoglobin levels.

- Blood transfusions should be used only for vital indications. Blood transfusions can usually be avoided even in severe forms of ID, unless the patient has developed myocardial ischemia or heart failure.

General iron deficiency in the body can be determined by the formula:

iron (mg) = (normal Hb – patient’s Hb) × body weight (kg) × 2.21 + 1000.

The resulting value will correspond to the value required to correct IDA and restore iron reserves in the body by 1000 mg. The duration of the course is variable, depends on the severity of the condition and can range from 4–5 weeks to 6 months of taking iron supplements, and it is necessary to take into account both the effectiveness of therapy and the occurrence of side effects and complications of the therapy. On average, patients with mild IDA should receive 150–200 mg of iron per day, and with moderate and severe IDA, 300–400 mg/day. The daily dose is divided into 2–4 doses.

At the moment, iron preparations are divided into two main groups: non-ionic and ionic compounds (Table 3).

In the treatment of IDA and ID, preference is given to compounds of ferric iron with a hydroxide-polymaltose complex (HPC), which include drugs such as Maltofer, Maltofer foul, etc. Preparations of this compound have a number of advantages: they repeat the properties of ferritin, which physiologically binds iron , the risk of exposure to free radicals is very low since iron is absorbed in the ferric state. Due to the large size of the molecules, their passive diffusion through the mucosal membrane occurs 40 times slower compared to the diffusion rate of the iron hexahydrate molecule. Fe (III) from HPA is absorbed in an active absorption process, only iron-binding proteins present in the gastrointestinal fluid and on the surface of the epithelium, can take up Fe(III) from HPA via competitive ligand exchange. These pharmacokinetic features provide the following advantages: high therapeutic efficacy, high safety, good tolerability (Table 4).

Prescribing iron supplements in combination with iron supplements, primarily folic acid and vitamin B12, can be especially effective, which allows you to quickly normalize hemoglobin levels and iron metabolism [22]. R. Geisser et al. showed that the use of the drug Maltofer fol, containing ferric iron and folic acid, in pregnant women can quickly normalize not only ferroindicators and hemoglobin levels, but also the content of folic acid [23]. Similar data were published by Beruti E., who showed the high effectiveness of prescribing iron CPC in combination with folic acid in the third trimester of pregnancy [24].

Parenteral administration of iron supplements is indicated only for patients with absorption disorders, intolerance to enteral drugs, and patients with chronic bleeding in which the need for iron cannot be satisfied by the enteral route. The main danger of parenteral therapy is the development of an anaphylactic reaction, especially in patients suffering from collagenosis. In this regard, drugs with a high degree of proven safety should be used for parenteral administration. Such drugs may include ferric iron hydroxide-sucrose complex (Venofer).

The effectiveness of therapy with iron supplements is based on the following criteria: reticulocyte reaction (the onset of the reaction is expected on days 3–4 from the start of therapy, peak on days 10–12), an increase in Hb levels is usually achieved at 3–4 weeks, disappearance of clinical manifestations of IDA after 1–2 months, overcoming tissue sideropenia 3–6 months from the start of treatment (ferritin control). Therapy with iron supplements continues until the ferritin concentration exceeds 50 ng/ml.

Thus, despite the fact that ID and IDA are a serious health problem for women of childbearing age, especially pregnant and lactating women, timely diagnosis and correctly prescribed treatment can effectively and quickly eliminate these disorders, avoiding their undesirable consequences.

Literature

- Danielson BG, Geisser P., Schneider W. Iron Therapy with Special Emphasis on Intravenous Administration, ISBN3–85819–223–6. 1996.

- Encyclopedia of Iron (CD edition). Vifor International, 2008.

- Chapman, Hall. Iron and women in the reproductive years. Report of the British Nutrition Foundation Task Force. Iron Nutritional and physiological significance. 1995.

- Breymann C., Major A., Richter C., Huch R., Huch A. Recombinant human erythropoietin and parenteral iron in the treatment of pregnancy anemia: a pilot study // J. Perinat. Med. Vol. 1995, 23: 89–98.

- Charlton RW, Bothwell TH Definition, Prevalence and Prevention of Iron Deficiency // Clinics in Hematology. 1982. V. 11: 309–325.

- WHO: The world health report 2002 - Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life.

- DeMaeyer EM, Dallman P., Gurney JM, Hallberg L., Sood SK, Srikantia SG Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anemia through primary health care. World Health Organization Geneva. 1989.

- Kagamimori S., Fujita T., Naruse Y., Kurosawa Y., Watanabe M. A longitudinal study of serum ferritin concentration during the female adolescent growth spurt // Annals of Human Biology. 1998. Vol. 15: 413–419.

- WHO. The prevalence of anemia in women: A Tabulation of available information. 1992.

- WHO. The World Health Report. 1998.

- Ivanyan A. N., Nikiforovich I. I., Litvinov A. V. Modern view of anemia in pregnant women // Russian Bulletin of Obstetrician-Gynecologist. 1, 2009, p. 17–20.

- Ideason L.I. Hypochromic anemia. M.: Medicine, 1981. 192 p.

- Konovodova E. N., Yakunina N. A. Iron deficiency conditions and pregnancy // Breast cancer. 2010, no. 19.

- Gevorkyan M. A., Kuznetsova E. M. Anemia in pregnant women: pathogenesis and principles of therapy // Breast cancer. 2011, No. 20.

- Siegenthaler W. Differential diagnosis innerer Krankheiten. Thieme Verlag, New York: 1994, 4.33–4.35.

- Breymann C., Honegger C., Holzgreve W., Surbek D. Diagnosis and treatment of iron-deficiency anemia during pregnancy and postpartum // Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010, Nov, 282 (5): 577–580.

- Shekhtman M. M. Guide to extragenital pathology in pregnant women. 2007.

- Chapman, Hall. Iron and women in the reproductive years. Report of the British Nutrition Foundation Task Force. Iron Nutritional and physiological significance. 1995.

- Tucker DM, Sandstead HH, Penland JG, Dawson SL, Milne DB Iron status and brain function: serum ferritin levels associated with asymmetries of cortical electrophysiology and cognitive performance // American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1984. Vol. 39: 105–113.

- Oski FA, Honig AS, Helu B., Howanitz P. Effect of iron therapy on behavior performance in non-anemic, iron-deficient infants // Pediatrics. 1983. Vol. 71:877–880.

- Lozoff B., Jimenez E., Wolf A.W. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency // New England Journal of Medicine. 1991. Vol. 325:687–694.

- Idelson L.I. Hypochromic anemia. M.: Medicine, 1981. 192 p.

- Gorodetsky V.V., Godulyan O.V. Iron deficiency conditions and iron deficiency anemia: treatment and diagnosis. Guidelines. M.: Medpraktika-M, 2005.

- Geisser P., Hohl H., Muller A. Klinische Wirksamkeit dreier verschiedener Eisenpraparate an Schwangeren // Schweiz. Apotheker-Zeitung. 1987. Vol. 14: 393–398.

- Beruti E. Oral treatment of multi-deficiency anemias of pregnant women with a combination of ferric polymaltose, folic acid and vitamin B12. Study report. 1978.

A. V. Malkoch*, Candidate of Medical Sciences L. A. Anastasevich**, Candidate of Medical Sciences N. N. Filatova*, Candidate of Medical Sciences

* GBOU DPO RMAPO, ** GBOU VPO RNIMU im. N. I. Pirogova, Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence