Pharmacological properties of the drug Stelara

Pharmacodynamics. Mechanism of action. Ustekinumab is a fully human IgG1k monoclonal antibody with high affinity and specificity for the p40 subunit of human interleukins (IL)-12 and IL-23. The drug blocks the biological activity of IL-12 and IL-23, preventing their binding to the IL-12Rβ1 protein receptor, which is expressed on the surface of immune cells. Ustekinumab cannot bind to IL-12 and IL-23, which are already bound to the receptor. Therefore, the drug cannot influence the formation of complement- or antibody-dependent cytotoxicity of cells bearing these receptors. IL-12 and IL-23 are heterodimeric cytokines that are secreted by activated antigen-presenting cells, particularly macrophages and dendritic cells. IL-12 and IL-23 take part in immune reactions, promote the activation of NK cells and the differentiation and activation of CD4+ T cells. However, in diseases associated with dysfunction of the immune system, dysregulation of the secretion of IL-12 and IL-23 is observed. Ustekinumab eliminates the effect of IL-12 and IL-23 on immune cell activation, in particular intracellular signal transduction and cytokine secretion caused by these ILs. Thus, it is assumed that ustekinumab interrupts the cascade of signal transduction reactions and cytokine secretion, which are critical in the development of psoriasis. Pharmacokinetics . Suction . The average time to reach Cmax in serum after a single subcutaneous administration of 90 mg ustekinumab to healthy volunteers was 8.5 days. In patients with psoriasis, this value at drug doses of 45 and 90 mg was the same as in healthy volunteers. Absolute bioavailability after a single subcutaneous administration to patients with psoriasis is 57.2%. Distribution . The median volume of distribution of ustekinumab in the terminal phase of elimination after a single intravenous administration to patients with psoriasis ranged from 57 to 83 ml/kg. Metabolism . The metabolic pathways of ustekinumab are not precisely known. Removal . The median systemic clearance of ustekinumab after a single intravenous administration to patients with psoriasis ranged from 1.99 to 2.34 ml/day/kg. The mean half-life of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis is approximately 3 weeks and ranged from 15 to 32 days in different studies. In a population pharmacokinetic analysis, apparent clearance (CL/F) and volume of distribution (V/F) were 0.465/day and 15.71, respectively, in patients with psoriasis. Gender did not influence the apparent clearance of ustekinumab. Population pharmacokinetic analysis showed a trend towards increased ustekinumab clearance in patients in whom antibodies to ustekinumab were detected. Dose linearity . The level of systemic action (Cmax and AUC) of ustekinumab increased in a dose-dependent manner after a single intravenous administration to patients with psoriasis in a dose range of 0.09–4.5 mg/kg or after a single subcutaneous administration in a dose range of 24–240 mg. Single and multiple administration . Following single and multiple subcutaneous administration of ustekinumab, serum AUC is generally predictable. After subcutaneous administration of Stelara at the 0th week and 4th week of treatment and then every 12 weeks, the equilibrium concentration in the blood serum is achieved before the 28th week and is 0.21–0.26 mcg/ml (45 mg) or 0.47–0.49 μg/ml (90 mg). With subcutaneous administration every 12 weeks, no accumulation of ustekinumab in the blood serum was detected. Effect of body weight on pharmacokinetics . Population pharmacokinetic analysis showed the influence of patient body weight on ustekinumab serum concentrations. In patients weighing 100 kg, the median serum drug concentration was almost 55% higher compared to patients weighing ≤100 kg. The median volume of distribution in patients weighing 100 kg was almost 37% higher compared with patients weighing ≤100 kg. The median ustekinumab serum concentration after a 90 mg dose in patients weighing 100 kg was comparable to that after a 45 mg dose in patients weighing ≤100 kg. Special populations of patients. The pharmacokinetics of ustekinumab in patients with renal or hepatic impairment have not been studied. No studies have been conducted in elderly patients. Population pharmacokinetic analysis showed no effect of smoking and alcohol intake on the pharmacokinetics of ustekinumab.

Stelara (Ustekinumabum) 90 mg/1 ml No. 1 - Instructions

Compound

The main functional substance is ustekinumab at a dose of 90 mg per milliliter of solution.

Other ingredients: L-histidine, L-histidine hydrochloride monohydrate, polysorbate 80, sucrose and water for injection.

Release form

Stelara is a clear to slightly opalescent (pearly) injectable solution, colorless to pale yellow. The solution may contain small amounts of translucent or white protein particles. Supplied in a cardboard box containing a single dose of medication in a 2 ml glass bottle.

pharmachologic effect

The active substance in Stelara, ustekinumab, is a monoclonal antibody. A monoclonal antibody is an antibody (a type of protein) that is designed to recognize specific structures (called antigens) in the body. Ustekinumab was designed to attach to two cytokines (messenger molecules) in the immune system called interleukin 12 and interleukin 23. These cytokines are involved in inflammation and other processes underlying psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. By blocking their action, ustekinumab reduces the activity of the immune system and reduces the symptoms of the disease.

Pharmacokinetics

Tmax of ustekinumab after subcutaneous administration is about 8.5 days; absolute bioavailability - 57.2%. The metabolism of the drug has not been fully studied. On average t1/2 is approximately 3 weeks (15–32 days). Pharmacokinetics are approximately linear.

Indications for use

The product is used to treat patients with:

- Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (a condition that causes red, scaly patches to appear on the skin). It is used in adults and children over 12 years of age who have not responded to other types of systemic (systemic) therapy for psoriasis, such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, or PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet light (UVA)), or for whom such treatment is not possible. PUVA is a treatment in which patients are given the medication psoralen before exposure to ultraviolet rays;

- active psoriatic arthritis (inflammation of the joints associated with psoriasis) in adults when the response to treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has been insufficient. Stelara can be used alone or with methotrexate (DMARD).

Contraindications

Stelara should not be used in patients with an active infection, or if you are allergic to the composition of the drug.

Side effects

The most common side effects of Stelara (seen in more than 5% of patients in clinical trials) are upper respiratory tract infections (colds), headache and nasopharyngitis. Most of these symptoms were considered mild and did not require discontinuation of treatment. The most serious side effect reported with Stelara is severe hypersensitivity (allergic reaction).

Drug interactions

During treatment, the administration of live viral or bacterial vaccines is not recommended. The safety and effectiveness of the combined use of ustekinumab and other immunosuppressive agents, including biologics or phototherapy, have not been studied. It is unknown whether the drug interferes with allergy immunotherapy.

Application and dosage

Stelara is administered by injection under the skin. The dose is determined by the doctor individually. For patients weighing less than 100 kg, the first recommended dose is 45 mg. After 4 weeks, a second dose is administered in the same amount. This is followed by maintenance therapy - 45 mg every 12 weeks. For people weighing more than 100 kg, the route of administration is the same, but the recommended dose is 90 mg. The safety and effectiveness of Stelara have not been established after more than 2 years of use.

Overdose

No data available.

special instructions

Before starting treatment, patients should be screened for tuberculosis infection. Particular caution should be exercised in patients with a positive history of malignancy or continuing treatment after the development of malignancy.

Use during pregnancy and breastfeeding

Use is contraindicated.

Impact on the ability to drive vehicles and operate machinery

No special precautions are required.

Terms of sale

As prescribed by a doctor.

Storage conditions

It is important to store the drug in its original packaging and in a dry and cool place, away from children.

Use of the drug Stelara

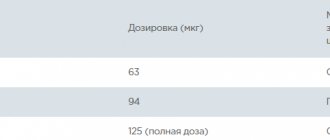

Stelara should be used by a physician experienced in the treatment of psoriasis. Dosing . Recommended dosing regimen: initial dose of 45 mg subcutaneously at week 0 and week 4 of treatment, then every 12 weeks. Interruption of treatment should be promptly considered in patients who do not achieve response before 28 weeks of treatment. Patients weighing 100 kg. For patients weighing 100 kg, a dose of 90 mg is administered subcutaneously at week 0, then 90 mg at week 4, and then every 12 weeks. In patients weighing 100 kg, a dose of 45 mg is also effective, but a dose of 90 mg provides greater effectiveness. Elderly patients (65 years and older) . No dose adjustment is required for elderly patients. Children and adolescents (under 18 years old) . Stelara is not recommended for use in children under 18 years of age due to the lack of data on safety and effectiveness. Impaired kidney and liver function . No studies of Stelara have been conducted in this category of patients and no recommendations regarding the dosage regimen can be made. Mode of application .

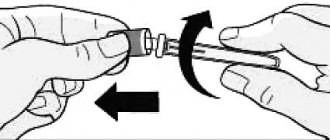

The drug should be used subcutaneously. If possible, do not inject into areas of skin with psoriatic lesions. At the discretion of the doctor, after appropriate training, the patient can administer subcutaneous injections of the drug to himself.

Side effects of the drug Stelara

The most common adverse reactions (10%) in controlled and uncontrolled clinical trials of Stelara for psoriasis were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infections. Most of these events were moderate and did not require discontinuation of treatment. Adverse reactions are classified by organ system and frequency: very often (≥1/10), often (≥1/100, ≤1/10), infrequently (≥1/1000, ≤1/100), rarely (≥1/10 000, ≤1/1000), very rare (1/10,000), unknown (cannot be estimated from available data). Within each frequency group, adverse reactions are presented in order of decreasing severity. Infections and infestations : very often - upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis; often - cellulitis, viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. Mental disorders : often - depression. From the side of the central nervous system : often - dizziness, headache. From the respiratory system : often - sore throat/pharynx, nasal congestion. From the gastrointestinal tract : often - diarrhea. From the skin and subcutaneous tissue : often - itching. From the musculoskeletal system : often - back pain, myalgia. General condition and local reactions : often - weakness, redness at the injection site; Uncommon: injection site reactions, including pain, swelling, itching, induration, bleeding, hematoma and irritation. Infections . In controlled trials of psoriasis, the incidence of infections and serious infections was similar with Stelara and placebo (infection rates 1.39 and 1.21 per year of treatment, respectively; serious infection rates 0.01 (5/407) and 0.01 (5/407), respectively. 02 (3/177) cases per person-year of treatment). In the controlled and uncontrolled portions of the clinical studies, the infection rate was 1.24 patient/year and the serious infection rate was 0.01 patient/year for patients treated with ustekinumab (24 serious infections in 2251 patients/year); Serious infections reported included cellulitis, diverticulitis, osteomyelitis, viral infections, gastroenteritis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections. When the drug Stelara was used in combination with isoniazid in patients with latent tuberculosis, no progression of tuberculosis was recorded in clinical studies. Malignant tumors . In placebo-controlled clinical trials of psoriasis, the incidence of malignancy (including melanoma, but not other forms of skin cancer) in patients receiving Stelara and placebo was 0.25 (1/406) and 0.57 (1/406), respectively. 177) cases per 100 person/years of treatment. The incidence of other (excluding melanoma) forms of cancer with the use of these drugs was 0.74 (3/406) and 0.57 (1/177) cases per 100 person-years of treatment, respectively. In the controlled and uncontrolled portions of clinical studies, the incidence of malignant tumors (including melanoma, but not including other forms of skin cancer) in patients receiving Stelara was 0.36 (8/2249) cases per 100 person-years of treatment; malignancies that were observed included breast, colon, head and neck, kidney, prostate and thyroid cancers. The incidence of malignancy in patients receiving Stelara was the same as in the general population (standardized rate ratio 0.68; 95% confidence interval: 0.29, 1.34). The incidence of other forms of cancer (excluding melanoma) with Stelara was 0.80 (18/2245) cases per 100 person-years of treatment. Hypersensitivity reactions. In clinical studies of Stelara, rash and urticaria were observed in less than 2% of patients. Immunogenicity. Approximately 5% of patients using ustekinumab developed antibodies to ustekinumab, usually at low titres. There was no clear correlation between the formation of antibodies and the presence of reactions at the injection site. In the presence of antibodies to the drug, a decrease in the effect was observed in patients, although the formation of antibodies does not exclude the achievement of a clinical effect.

Experience with the use of secukinumab in the treatment of severe resistant psoriasis

Improving the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris (VP) remains an important medical and social problem, which is associated with the persistently high incidence of this dermatosis in the Russian Federation and the chronic relapsing course of the disease. In recent years, there has been an increase in the formation of severe, disabling forms of the disease, the torpidity of the process and the ineffectiveness of standard therapeutic approaches are observed, and the formation of iatrogenic complications is recorded [1, 2].

General approaches to the treatment of psoriasis (Ps), taking into account the characteristics of the clinical forms and manifestations of the disease, the severity of the process and comorbid pathology, are presented in domestic clinical recommendations, in the guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis of European countries and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, EADV) [3, 4].

The most difficult task is the treatment of patients with moderate and severe psoriasis, in whom almost half of the cases have psoriatic joint damage, manifested in the formation of distal arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis; mono- or polyarthritis, spondylitis [3, 5].

Patients with moderate and severe manifestations of psoriasis are considered to be those who have widespread skin rashes, characterized by severe inflammatory infiltration, peeling in patches, itching of the skin, when the standardized PASI psoriasis severity index is more than 10–12 points, “problem” areas are affected - the face, neck , scalp, anogenital area; The quality of life of patients is critically reduced. It is for such patients, in addition to the existing pathogenetically oriented methods of therapy using pharmacological agents with anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, absorbable effects, and the use of photo- and photochemotherapy methods, that genetically engineered biological preparations (GEBPs) have been developed and are widely used - monoclonal antibodies with high affinity to the determinants of activated lymphocytes and circulating cytokines, neutralizing their influence and interrupting the process of psoriatic plaque formation [2, 3, 6].

The introduction of biologically active drugs into clinical practice over the past decade has led to a significant paradigm shift in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as chronic inflammatory diseases that require long-term therapy to maintain an effective clinical response. Long-term use of biologically active drugs with immunosuppressive effects for the treatment of patients with PS and PsA involves the assessment of a complex of factors, including the degree of effectiveness of treatment, its stability, the possibility of the formation of adverse events associated with the formation of anti-drug antibodies, potential dangers associated with a decrease in the activity of the immune response to infectious agents and during the development of neoplasia [4, 7]. For these purposes, the indicator “drug survival” is used, that is, through long-term observation, the period during which the patient remains on this type of therapy is established.

For a number of years, a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness, safety and outcomes of therapy for patients with PS and PsA has been carried out within the framework of the global international prospective, observational study PSOLAR (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry), which brings together more than 12 thousand patients with PsA receiving systemic, including genetically engineering biological therapy (GEBT). Studies have shown that GEBD are effective in the initial stage of treatment of the disease, but the clinical response decreases over time and even with modification of therapy, ultimately leading to suspension of therapy or switching to GEBT of a different mechanism of action [8, 9]. At the same time, a shorter period of “drug survival” was established for the class of TNF blockers than for a drug that inhibits the cytokines IL-12/23 [8].

The possibility of switching from one GIBT to another if the effect “eludes” or if contraindications or adverse events appear is described in a number of publications summarizing the use of GIBT in real clinical practice, and allows for a wide variety of switching options both within one class of drugs and between them [8 , 10, 11]. In domestic clinical practice, most often, initial therapy for PS and PsA is carried out using anti-TNF-α drugs (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept); if effectiveness is lost, treatment with ustekinumab is prescribed [2].

In the State Budgetary Institution SO UrNIIDVII, treatment of patients with severe, resistant forms of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with the use of biologically active drugs has been carried out since 2006, over a 10-year period more than 2200 administrations of biological drugs were carried out.

In the period until 2013, GIBT was provided to citizens of the Russian Federation within the framework of high-tech medical care (HTMC) in the “dermatovenereology” profile from the federal budget. Type of assistance 05.00.002 - treatment of severe, resistant forms of psoriasis, including psoriatic arthritis, with the use of biologically active drugs. During the specified period, 135 patients received treatment with the GEBD infliximab at the State Budgetary Institution SO UrNIIDVII.

From 2014 to the present, residents of the Sverdlovsk region receive GIBT as part of the VMP, included in the basic compulsory health insurance (CHI) program. One type of such assistance is the treatment of patients with severe resistant forms of psoriasis using genetically engineered biological drugs and treatment using genetically engineered biological drugs in combination with immunosuppressive drugs. Total for the period 2014–2016. 25 patients were treated under VMP in compulsory medical insurance.

In addition, since 2014, the order of the Ministry of Health of the Soviet Union has defined additional measures and schemes for providing medical care to patients with severe, widespread, torpid forms of psoriasis using genetically engineered pharmaceuticals. For this purpose, clinical and statistical groups (CSGs) have been identified to provide specialized medical care to patients in a day hospital, taking into account the specific GIBD, the frequency of its administration and cost. Currently, 16 patients annually receive this type of medical care at the State Budgetary Institution SO UrNIIDVII, of which 2 (12.5%) receive etanercept, 4 (25.0%) ustekinumab and 12 (75.0%) adalimumab. A 100% examination carried out by the Territorial Compulsory Medical Insurance Fund, which included control of the volume, timing, quality and conditions of medical care in the State Budgetary Institution SO UrNIIDVII, revealed shortcomings in less than 0.2% of cases; There are no penalties.

Since 2021, together with the territorial compulsory medical insurance fund, work has been carried out to change and supplement the DRG (subgroups) taking into account the registration in the Russian Federation of new and expansion of indications for already registered biological medications, which will increase the volume of specialized medical care for patients with severe forms of psoriasis, torpid to traditional ones and reserve methods of therapy.

Since July 2021, a new biologically active drug, secukinumab (Cosentyx), has been registered in the Russian Federation. Secukinumab is a fully human antibody immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), which specifically inhibits the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-17A (IL-17A), reduces the degree of its interaction with IL-17 receptors, which are expressed by activated lymphocytes, keratinocytes and synoviocytes, which determine the development of the psoriatic process, that is, it provides a selective effect on the key cause of the development of symptoms of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [12, 13]. Clinical studies of the drug secukinumab have shown that it provides a rapid onset of clinical effect with a decrease in the severity of inflammation and infiltration of psoriatic plaques already in the third week of treatment; Therapy of patients with psoriasis with Cosentyx for 4 years determines the state of “clear” or “almost clear” skin in the vast majority of patients, achieving PASI 90 in 8 out of 10 patients and PASI 100 in 4 out of 10 patients with psoriasis [14, 15]. In patients with PsA, secukinumab provides a rapid onset of clinical effect after the first week of treatment; in 84% of patients, it determines the absence of radiological progression of structural joint damage within 2 years; promotes active regression of enthesitis and dactylitis by 70% and 80%, respectively [16, 17].

Cosentyx demonstrates a favorable safety profile both in clinical studies and in real clinical practice in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The most common adverse events are upper respiratory tract infections (nasopharyngitis and rhinitis); the drug has low immunogenicity (< 1% of cases, the formation of non-neutralizing antibodies to secukinumab was observed), which does not affect its effectiveness [18]. Cosentyx demonstrated high efficacy both in “bionaive” patients with PS and PsA, and when used in patients who had previously received GEBD. Important are the results of comparative clinical studies that showed the superior effectiveness of secukinumab over etanercept both in the short and long term (at 4 and 52 weeks of observation), as well as higher efficiency than ustekinumab (~20%) in level of achieving PASI 90 within 52 weeks of treatment [15, 19].

In this article, we present the first clinical observation of effective therapy with an IL-17A blocker (secukinumab) in a patient with severe, treatment-resistant PS and PsA.

Clinical case

Patient V., born in 1960, resident of Yekaterinburg, music teacher. Diagnosis: widespread papular and plaque non-seasonal psoriasis, partial erythroderma, torpid often relapsing course, resistant to traditional, including cytostatic methods of therapy. Psoriatic peripheral polyarthritis, high-grade spondylitis.

Concomitant diagnoses: arterial hypertension stage II, stage 2, risk group 3. Iron deficiency anemia.

I have been suffering from psoriasis for more than 30 years. The onset of the disease is not associated with anything. The diagnosis was established at the first visit, by a dermatologist at the place of residence. The process immediately acquired a widespread, often recurrent course, with exacerbations occurring out of season. She was constantly monitored and received outpatient treatment from a dermatologist at her place of residence (standard methods of therapy). After 3 years from the onset of the disease, the skin process acquired a continuously relapsing character. She repeatedly received treatment in the UrNIIDVII hospital (cytostatic therapy with methotrexate, PUVA therapy), but it was not possible to achieve stable remission. Since 2003, lesions of peripheral joints have appeared. She was constantly observed by a rheumatologist, received outpatient and inpatient treatment: methotrexate, plasmapheresis, pulse therapy with prednisone, without a pronounced effect, but with the formation of persistent intolerance to methotrexate. From 2005 to 2006, she received immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporine with good effect on both skin and joint processes. However, due to the development of side effects (hypertension), the drug was discontinued, after which a deterioration in skin and joint processes was noted.

Considering the severity of the clinical manifestations of dermatosis, reluctance to previous treatment methods, the continuously relapsing course of the disease, and significant joint damage, the patient received therapy with infliximab at a dose of 300 mg every 8 weeks in the period 2007–2011. Against the background of GIBT, drug remission of the disease was achieved, however, during the fourth year of therapy, a gradual increase in resistance to the drug was observed, and due to a decrease in its effectiveness, the drug was discontinued.

After stopping the administration of biologically active drugs, a sharp deterioration in skin and joint processes was noted, which again acquired a continuously relapsing off-season course. Outpatient therapy (methotrexate, topical glucocorticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) was without effect, there was poor tolerability of cytostatic therapy with the development of dyspeptic disorders, abnormalities in the biochemical hepatogram, and the psoriatic process progressed. In this regard, since 2014, the patient was treated with ustekinumab according to the standard regimen as a basic staged HIBT. The therapy was tolerated well, without complications or side effects, however, from June 2021, after the 7th administration of the drug, there was a significant decrease in the effectiveness of this method of therapy: the appearance of fresh psoriatic rashes, increased pain and swelling of peripheral joints.

It was stated that in this patient the psoriatic process was characterized by a particularly severe course with pronounced clinical manifestations and a continuously relapsing nature, was resistant to standard methods of systemic therapy, and treatment with GIBD, carried out with anti-TNF and anti-IL-12/23 drugs, demonstrated action effective only for a limited time.

By the decision of the medical commission of the State Budgetary Institution Siberian UrNIIDVII, the patient was started on therapy with a gastrointestinal biological agent - secukinumab.

Before starting this therapy:

Status localis. The skin process is common, localized on the skin of the face, scalp, torso, flexor and extensor surfaces of the extremities. It is represented by many numular papules and plaques up to 20.0 cm in diameter with unclear boundaries, moderately and heavily infiltrated. On the surface of the rash there is a mass of scales, tightly fitting, white. Peeling is medium-plate, abundant. The psoriatic triad is positive, pronounced isomorphic Koebner reaction. Dermographism pink. PASI index - 51.5 points. The nail plates are completely affected - with areas of subungual hyperkeratosis, a symptom of an “oil stain”. The volume of active and passive joints of the hands, feet, cervical spine, right elbow, and knee joints is limited. The joints are swollen and hot to the touch. O deformity, axial arthritis, dactylitis and “sausage-shaped” deformity of the fingers and toes (Fig. 1).

Before the start of therapy, a general clinical blood test: red blood cells 3.97 × 1012/l, hemoglobin 95 g/l, leukocytes 6.0 × 109/l, neutrophils 71.7%, lymphocytes 17.4%, eosinophils 3.1%, monocytes 7.2%, ESR 40 mm/hour. General urine test, biochemical hepatogram - no abnormalities.

X-ray examination of the lungs in two projections - without pathology, the patient was consulted by a phthisiatrician, tuberculosis was excluded.

The drug secukinumab is prescribed at a dose of 300 mg, according to the instructions for use of the drug in the form of subcutaneous injections. The initial course was 5 weeks with weekly administration of secukinumab. Subsequently, therapy was continued in the form of monthly subcutaneous injections.

During therapy, already on the 3rd day after the first administration of the drug secukinumab, positive dynamics were noted in both skin and joint processes. In Fig. Figure 2 shows the patient on the 7th day of therapy.

After carrying out the initiating course for 5 weeks, almost complete regression of the rash was noted, the PASI index was 0 (Fig. 3).

When the course of treatment with secukinumab is continued for up to 24 weeks, the state of clinical remission of the skin process is maintained, joint symptoms are minimal, quality of life is completely restored, and the patient has returned to professional activities (Fig. 4).

Treatment with secukinumab was well tolerated; there were no adverse events; laboratory monitoring of the hemogram and biochemical hepatogram in the dynamics of treatment did not reveal any deviations.

Discussion

In everyday clinical practice, there are frequent cases of the development of severe forms of PS and PsA in young and middle-aged people, when the process has a continuously recurrent course, critically reduces the quality of life and determines long-term disability. Therapy for such patients is carried out with systemic pathogenetically oriented drugs that have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects with alternating agents and treatment methods: phototherapy and its combined variants, photochemotherapy, methotrexate, retinoids, cyclosporine, biologically active drugs [3, 4]. However, even after using the entire available arsenal of treatments, there remain patients who cannot control PS and PsA at an acceptable level.

Promising for such a cohort of patients is the use of new, targeted, highly effective and safe drugs, which include the IL-17A blocker drug secukinumab, and for dermatovenereologists it is extremely important to accumulate and generalize their own positive clinical experience.

Conclusion

The presented observation demonstrates the high clinical effectiveness of the drug Cosentyx (secukinumab) in the treatment of a patient with extremely severe PS and PsA, who has developed resistance to standard methods of systemic therapy, secondary ineffectiveness of monoclonal antibodies to TNF-α and IL-12/23. The achieved rapid and stable treatment effect over 6 months (PASI 100) indicates the rationality of the use of secukinumab in complex clinical situations, the need for wider introduction of the drug into domestic clinical practice, which will help quickly improve the course of the disease and the quality of life of patients suffering from moderate and severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Literature

- Kubanova A. A., Kubanov A. A., Melekhina L. E., Bogdanova E. V. Organization of medical care in the “dermatovenereology” profile in the Russian Federation. Dynamics of incidence of sexually transmitted infections, diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, 2013–2015. // Bulletin of dermatology and venereology. 2016; (3): 12–28.

- Kungurov N.V., Kokhan M.M., Keniksfest Yu.V. Biological therapy of patients with severe forms of psoriasis // Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology. 2012; 4:91–95.

- Federal clinical guidelines. Dermatovenereology 2015: Skin diseases. Sexually transmitted infections. 5th ed., revised. and additional M.: Business Express, 2021. 768 p.

- Nast A., Gisondi P., Ormerod AD, Saiag P., Smith C. et al. European S3-Guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Update 2015. Short version. EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC // JEADV. 2015; 29:2277–2294.

- Korotaeva T.V., Nasonov E.L., Molochkov V.A. The use of methotrexate in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis // Modern Rheumatology. 2013; 2:1–8.

- Kungurov N.V., Kokhan M.M., Keniksfest Yu.V., Filimonkova N.N. Immunosuppressive and biological therapy of patients with severe forms of psoriasis // Bulletin of Ural Medical Science. 2011; 2 (2): 35–39.

- Knud Kragballe K., van de Kerkhof PCM, Gordon KB Unmet needs in the treatment of psoriasis // Eur J Dermatol. 2014; 24(5):523–532.

- Menter A., Papp KA, Gooderham M., Pariser DM, Augustin M. Drug survival of biological therapy in a large, disease-based registry of patients with psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR) // JEADV. 2016; 30: 1148–1158.

- Davila-Seijo P., Dauden E., Carretero G., Ferrandiz C., Vanaclocha F. Survival of classic and biological systemic drugs in psoriasis: results of the BIOBADADERM registry and critical analysis // JEADV. 2016; 30: 1942–1950.

- Inzinger M., Wippel-Slupetzky K., Weger W., Richter L., Mlynek A. et al. Survival and Effectiveness of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Inhibitors in the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis under Daily Life Conditions: Report from the Psoriasis Registry Austria // Acta Derm Venereol. 2016; 96:207–212.

- Mrowietz U., de Jong EMGJ, Kragballe K., Langley R., Nast A., Puig L., Reich K. A consensus report on appropriate treatment optimization and transitioning in the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis // JEADV . 2014; 28:438–453.

- Langley R., Elewski B.E., Lebwohl M. et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis — results of two phase 3 trials // N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:326–338.

- Mansouri Y., Goldenberg G. New Systemic Therapies for Psoriasis // Cutis. 2015; 95 (3): 155–160.

- Blauvelt A., Prinz JC, Gottlieb AB et al. Secukinumab administration by pre-filled syringe: efficacy, safety, and usability results from a randomized controlled trial in psoriasis. (FEATURE) // Br J Dermatol. 2015; 172:484–493.

- Thaçi D., Blauvelt A., Reich K., Tsai TF, Vanaclocha F., Kingo K. et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015; 73:400–409.

- Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B. et al. FUTURe 1 Study Group. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic Arthritis // N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(14):1329–1339.

- McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B. et al. FUTURe 2 Study Group. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURe 2): a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial // Lancet. 2015; 386:1137–1146.

- Van de Kerkhof PC, Griffiths CE, Reich K., Leonardi CL, Blauvelt A. et al. Secukinumab long-term safety experience: A pooled analysis of 10 phase II and III clinical studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75(1):83–98.

- Strober B., Gottlieb AB, Sherif B., Mollon P., Gilloteau I. et al. Secukinumab sustains early patient-reported outcome benefits through 1 year: Results from 2 phase III randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials comparing secukinumab with etanercept // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017; 76(4):655–661.

N. V. Kungurov, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor N. V. Zilberberg, Doctor of Medical Sciences M. M. Kokhan1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Yu. V. Keniksfest, Doctor of Medical Sciences E. V. Grishaeva, Candidate of Medical Sciences

GBU SO UrNIIDVII, Yekaterinburg

1 Contact information

Experience with the use of the drug secukinumab in the treatment of severe resistant psoriasis / N.V. Kungurov, N.V. Zilberberg, M.M. Kokhan, Yu.V. Keniksfest, E.V. Grishaeva.

For citation: Attending physician No. 11/2017; Page numbers in issue: 17-23 Tags: skin diseases, dermatosis, arthritis, secukinumab

Special instructions for the use of Stelara

Infections . Stelara is a selective immunosuppressant and may increase the risk of developing infections and reactivation of latent infections. In clinical studies, serious bacterial, fungal and viral infections were observed in patients using Stelara. The drug should be used with caution in patients with chronic infections or a history of recurrent infections. Before starting to use the drug Stelara, it is necessary to examine the patient for the presence of tuberculosis. The drug should not be used in patients with active tuberculosis. If you have latent tuberculosis, treatment should begin before using Stelara. It is also necessary to begin treatment for tuberculosis before using Stelara in patients with a history of latent or active tuberculosis and in whom the sufficient effect of previous treatment has not been confirmed. During and after treatment with the drug, patients should be carefully examined in order to promptly identify signs and symptoms of active tuberculosis. Patients should be instructed to seek medical attention if they develop signs and symptoms that suggest the development of an infection. If a serious infection develops, patients should be closely monitored; Stelara should not be used until the infection is cured. Malignant tumors . The drug Stelara is a selective immunosuppressant. Drugs in this group may increase the risk of developing malignant tumors. Some patients treated with this drug in clinical studies developed skin and other types of malignant tumors. No studies on the use of Stelara have been conducted in patients with a history of malignant tumors. Caution should be used when using the drug in patients who have a history of malignant tumors or when considering continuing treatment after the development of such a tumor. Hypersensitivity reactions . If anaphylactic or other serious allergic reactions develop, the use of Stelara should be stopped immediately and appropriate treatment should be prescribed. Vaccination . During treatment with Stelara, it is not recommended to use live viral and bacterial vaccines (such as the BCG vaccine). No specific studies have been conducted in patients who have recently been vaccinated with live viral or live bacterial vaccines. Before using live viral and bacterial vaccines, treatment with Stelara should be delayed for less than 15 weeks after the last dose and can be resumed 2 weeks after vaccination. The doctor should know about the peculiarities of using the drug and specific vaccines and immunosuppressants before and after vaccination. Inactivated vaccines and vaccines from killed microorganisms can be used simultaneously with Stelara. Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy . The safety and effectiveness of Stelara in combination with immunosuppressants and phototherapy have not been studied. If it is necessary to use the drug Stelara, it is necessary to weigh the advantages of its simultaneous use with immunosuppressants. Special categories of patients Use in pediatric practice (up to 18 years of age) . No specific studies have been conducted on the use of Stelara in children. Application in geriatric practice (65 years and older) . The effectiveness and safety of the drug in patients over 65 years of age and in younger patients did not differ significantly. Since the incidence of infections in elderly patients is generally higher, caution should be exercised when treating patients in this age group. Liver and kidney failure . No special studies have been conducted on the use of Stelara in patients with liver and kidney failure. Special safety precautions . The solution of the drug Stelara in the bottle should not be shaken. Before subcutaneous administration, the solution in the bottle should be visually checked for the presence of mechanical inclusions or color changes. It should be clear or slightly opalescent, colorless or slightly yellowish and may contain trace amounts of small clear or white protein particles. This appearance is not unusual for protein solutions. If there is a change in color, cloudiness or the presence of solid particles, the solution cannot be used. Before using the drug, the solution must reach a comfortable temperature for injection (approximately within 30 minutes). Stelara does not contain preservatives, so any unused remainder of the drug in the vial and syringe cannot be reused. Unused drug and waste must be destroyed in accordance with generally accepted requirements. During pregnancy and breastfeeding . There is insufficient data regarding the use of Stelara during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown no direct or indirect negative effects on pregnancy, embryonic development, childbirth or postnatal development. As a preventative measure, it is recommended to avoid the use of Stelara during pregnancy. Women of reproductive age must use adequate contraception throughout the course of treatment and for 15 weeks after its completion. It is not known whether ustekinumab passes into breast milk. Animal studies have shown low levels of penetration into breast milk. It is not known whether the drug is absorbed systemically after absorption. Since Stelara may cause adverse reactions in infants, a decision must be made to stop breastfeeding while taking the drug and for 15 weeks after treatment, or to discontinue therapy. The benefit/risk ratio should be carefully weighed before deciding whether a woman needs treatment or continues breastfeeding. Children . The safety and effectiveness of the drug in this age category have not been studied. Therefore, the drug is not recommended for use in children under 18 years of age. The ability to influence reaction speed when driving vehicles or working with other mechanisms. Studies of the effect of the drug on the reaction rate when driving vehicles or working with other mechanisms have not been conducted.

Ustekinumab in the treatment of ulcerative colitis

Currently, new methods of treating inflammatory bowel diseases, including biological drugs, are being actively developed. The drug ustekinumab, recently registered for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease, is an antagonist of interleukins 12 and 23. This review is devoted to the analysis of the effectiveness and safety of this drug in patients with UC based on data from a phase III clinical trial and data from cohort studies in real clinical practice. In studies, ustekinumab showed high efficacy in both induction and maintenance therapy of UC and was superior to placebo in most parameters assessed (clinical, endoscopic and histological remission). In addition, the drug demonstrated a good safety profile.

Introduction

Drug therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) is actively developing. IBD, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD), is a chronic, relapsing inflammation affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Due to the progressive nature of these diseases, patients often require lifelong drug therapy [1, 2].

Over the past two decades, the first and main biological therapy for moderate to severe forms of IBD has been tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha antagonists. However, up to 1/3 of patients do not respond to initial anti-TNF therapy (primary non-responders), and up to 40% of responders eventually lose response (secondary non-responders) [3]. Moreover, anti-TNF therapy is associated with rare but severe side effects, including paradoxical autoimmune reactions, serious infections and malignancies [4–6].

Thus, there is clearly an increasing need for new drug treatments that are safe and effective for IBD.

With a better understanding of the pathophysiology of IBD, new therapeutic targets have emerged in recent years. One of them is interleukins (IL) 12 and 23. IL-12 and IL-23 induce T-lymphocyte differentiation, which leads to upregulation of inflammatory cytokines.

IL-23 is a proinflammatory heterodimeric cytokine composed of p40 and p35 subunits. Before the discovery of IL-23, IL-12, which consists of the common p40 subunit, was considered a major mediator of inflammation [7]. An early clinical trial evaluating anti-IL-12 monoclonal antibodies showed some promise in patients with active CD [8]. Later it became obvious that the p40 subunit, common to IL-12 and IL-23, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases [9, 10]. IL-12 and IL-23 induce inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa by promoting the differentiation of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes into T helper 1 and T helper 17 cells, which subsequently leads to upregulation of inflammatory cytokines [11–13].

Ustekinumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. As a result, the receptors of these pro-inflammatory cytokines on cells are blocked [14]. Ustekinumab was first approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in 2009, and in 2021 for the treatment of moderate to severe CD [15]. In 2021, the drug was also approved for the treatment of UC. Currently, ustekinumab is registered in Russia for the treatment of moderate and severe CD and UC. The drug is included in international and Russian recommendations for the management of patients with moderate and severe CD and UC.

Efficacy of ustekinumab: clinical trial data

The efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe UC was assessed in a phase III study (UNIFI) using doses identical to those in the phase III study in patients with CD [16].

The study included adult patients (≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of UC at least three months before screening, moderate to severe activity, defined as a total Mayo score of 6 to 12, and an endoscopic Mayo score of 2 or 3 [ 17, 18] and scores for each of the four parameters of the Mayo scale from 0 to 3. Eligible patients were required to have an inadequate response or side effects to anti-TNF drugs, vedolizumab, or disease-modifying (nonbiologic) therapy. Patients took stable doses of aminosalicylates and immunosuppressants from the time of inclusion until the 44th week of maintenance therapy. Those receiving oral corticosteroids (OCS) at enrollment continued at a stable dose during induction and tapered when maintenance treatment began.

Previous treatment with IL-12 or IL-23 antagonists was prohibited. Previous anti-TNF therapy was discontinued at least eight weeks before study entry, and vedolizumab therapy was discontinued at least four months before study entry. Other background therapy was discontinued at least 2–4 weeks before inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria included indications for colectomy, gastrointestinal diseases that could lead to surgery or complicate assessment of disease activity, cancer, and active infections (including tuberculosis). Thus, in this clinical study, for the first time, the effectiveness of genetically engineered biological drugs (GEBD) was studied in the most severe category of patients with an inadequate response or side effects not only to anti-TNF therapy, but also to vedolizumab (multiple “non-responders”).

At week 0 of induction therapy, patients were randomly assigned to three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio. Patients in the first group received a single intravenous infusion of ustekinumab 130 mg, patients in the second received ustekinumab at a body weight dose of approximately 6 mg/day. kg, patients of the third - placebo. Randomization was based on previous biologic treatment failure and geographic region (Eastern Europe, Asia, or rest of the world).

The maintenance study included patients with a clinical response to intravenous ustekinumab at week eight and those who did not respond to intravenous placebo and then received an induction dose of intravenous ustekinumab (6 mg/kg) at week eight and had a response at week 16. th week. Response to therapy was defined as a ≥ 30% reduction in Mayo total score and ≥ 3 points from baseline, with a corresponding ≥ 1 point reduction in Mayo rectal bleeding score and a rectal bleeding score of 0 or 1. At week 0 of maintenance therapy, patients were randomly assigned to three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio. The first group received subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 weeks, the second every eight weeks, and the third placebo until the 40th week. Randomization was carried out taking into account intravenous induction therapy, the presence of clinical remission at the initial level of maintenance therapy and oral corticosteroids.

Patients who did not respond to intravenous ustekinumab at week eight received ustekinumab 90 mg subcutaneously and were reevaluated at week 16. Those who responded entered a maintenance study and received ustekinumab 90 mg subcutaneously every eight weeks. Such patients were considered delayed responders to ustekinumab. Those who responded to intravenous placebo at week eight then received subcutaneous placebo.

The primary endpoint for the induction therapy study was clinical remission (defined as a Mayo total score ≤ 2 and any parameter ≤ 1) at week eight. The primary secondary endpoints at week eight were endoscopic remission (defined as a Mayo endoscopic score of 0 or 1), clinical response, and change from baseline in IBDQ score. The secondary endpoint at week 8 was histoendoscopic mucosal healing, which required both histological remission (defined as neutrophil infiltration in less than 5% of crypts, absence of crypt destruction and absence of erosions, ulcerations or granulation tissue) [19, 20] and endoscopic remission. In the maintenance study, the primary endpoint was clinical remission at week 44. Primary secondary endpoints were maintenance of clinical response to week 44, endoscopic remission at week 44, steroid-free clinical remission at week 44, and maintenance of clinical remission to week 44 in patients with clinical remission at baseline during maintenance therapy.

Separately, histologic remission, histoendoscopic mucosal healing, and changes in partial Mayo scores, IBDQ scores, serum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations, and fecal biomarker concentrations were assessed separately in both arms of the study. Follow-up safety assessments were conducted during induction therapy until week eight or 16 when patients entered the maintenance study, or 20 weeks after the final induction dose for those who discontinued the study, and during maintenance therapy until week 44. weeks (i.e. 52 weeks of treatment).

Induction of remission

The induction therapy study included 961 patients. After randomization, 319 patients received placebo, 320 patients received ustekinumab 130 mg, and 322 patients received ustekinumab 6 mg/kg.

Among the 51.1% of randomized patients who failed prior biologic treatment (491 of 961), a total of 98.8% (485 of 491) failed treatment with at least one TNF antagonist. In 32.6% (160 of 491), treatment with both a TNF antagonist and vedolizumab was ineffective, and in 1.2% (6 of 491) treatment with vedolizumab alone was ineffective.

At week eight, the percentage of patients in clinical remission in the groups receiving ustekinumab 130 mg (15.6% (50 of 320 patients)) or 6 mg/kg (15.5% (50 of 322 patients)) was higher than in placebo group (5.3% (17 of 319)) (p

Among patients who did not have a clinical response to intravenous ustekinumab and who received 90 mg subcutaneous ustekinumab at week eight, a total of 59.7% (139 of 233) had a delayed clinical response at week 16. Among all patients in the induction trial, 77.6% of patients (498 of 642) initially prescribed ustekinumab experienced a clinical response at 16 weeks. Additionally, among patients who did not have a clinical response to IV placebo and then received IV ustekinumab 6 mg/kg, 67.9% (125 of 184) had a clinical response at week 16.

Results from pre-study treatment-by-treatment analyzes suggest benefits of ustekinumab in different patient subgroups.

The proportion of patients achieving key secondary endpoints or having histoendoscopic mucosal healing was significantly higher in both ustekinumab groups compared with the placebo group. At week eight, mean changes in IBDQ scores from baseline were greater in both ustekinumab groups compared with the placebo group. The proportion of patients with histological improvement at week 8 was higher in both ustekinumab groups than in the placebo group. Significant versus placebo improvements in fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin and serum CRP concentrations compared with baseline levels support the clinical results obtained.

In conclusion, ustekinumab is more effective than placebo in inducing clinical remission after eight weeks. This effect was observed in all patients regardless of the failure of previous biologic therapy, including patients who had not previously received biologics. The results of the evaluation of the effectiveness of ustekinumab therapy at week 16 showed that 87% of patients who had not previously received GEBP and 80% of patients in the combination group achieved a clinical response [21].

The effect of ustekinumab occurred soon after induction: according to BE Sands et al. [22], symptom improvement (patient-rated stool frequency and presence of rectal bleeding) was recorded daily for seven days before each visit. Partial Mayo scores were performed at baseline and week 2 using the average of stool frequency and rectal bleeding scores for the most recent period of three consecutive days before the visit. During the visit, values on the Physician's General Assessment Scale were recorded. Reductions in systemic inflammation (CRP and fecal biomarkers assays performed at baseline and day 14) were observed as early as the first assessments on days seven and day 14, respectively.

Maintenance therapy

The maintenance therapy study included 783 patients [16]. Among patients who demonstrated a clinical response to ustekinumab induction therapy, the proportion who were in clinical remission at week 44 (52 weeks after intravenous induction) in the ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 groups (38.4% (66 of 172 patients) )) or eight weeks (43.8% (77 of 176)) was significantly higher than the placebo group (24.0% (42 of 175)) (p = 0.002 and p

The proportion of patients with sustained clinical response to week 44, endoscopic remission at week 44, or clinical remission without corticosteroids (by any definition of clinical remission) at week 44 was significantly higher in both ustekinumab groups than in the placebo group. Among patients receiving corticosteroids at baseline, the proportion who discontinued corticosteroids at least 90 days before week 44 in the ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 (67% (55 of 82 patients)) or eight weeks (77) groups % (71 of 92)) was higher than in the placebo group (44% (40 of 91)). Patients receiving ustekinumab (median seven weeks in each group) stopped taking corticosteroids earlier than patients receiving placebo (median 16 weeks).

The proportion of patients who experienced both histological remission and histoendoscopic mucosal healing was higher in both ustekinumab groups than in the placebo group. At week 44, mean IBDQ scores improved or remained unchanged from baseline with ustekinumab every 12 and eight weeks, but worsened with placebo. Improvements in partial Mayo scores and concentrations of CRP, lactoferrin, and calprotectin observed at the time of entry into the maintenance study were maintained in both ustekinumab groups, whereas these values worsened in the placebo group.

Among patients who demonstrated a delayed response to ustekinumab and received 90 mg every eight weeks, 62.4% (98 of 157) had a clinical response at week 44. There were fewer patients who met this endpoint or other efficacy measures at week 44 than patients who responded to intravenous ustekinumab and who received 90 mg of ustekinumab subcutaneously every eight weeks during maintenance therapy.

In conclusion, among patients who responded to induction therapy with intravenous ustekinumab and underwent a second randomization, the likelihood of clinical remission at 44 weeks was higher in the subcutaneous ustekinumab groups compared with the placebo group. For all prespecified primary secondary endpoints in the induction and maintenance studies, the percentages of patients were significantly higher in the ustekinumab groups compared with the placebo group.

All patients who completed week 44 of the maintenance study and met inclusion criteria for long-term follow-up continued to receive ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 or eight weeks. Ustekinumab dose adjustments (from every 12 to eight weeks or a dummy dose adjustment from every eight weeks to eight weeks) were provided from week 56. Patients who continued to take placebo were excluded from this part of the study. During the maintenance therapy study, all patients receiving corticosteroids at baseline were recommended to gradually reduce the dose of these drugs. Of the 284 patients in the randomized population receiving ustekinumab maintenance, 139 received corticosteroids at baseline maintenance. At week 92 of the long-term follow-up period, the rate of symptomatic remission without and with the use of corticosteroids was calculated using ITT analysis (intention-to-treat). Findings were similar for maintenance doses of ustekinumab 90 mg every eight and 12 weeks. Among those who received ustekinumab and were in symptomatic remission at week 92, 98.4% (182/185) were not taking corticosteroids.

Safety of ustekinumab in the treatment of UC

In the induction therapy study, 41.4% of patients in the ustekinumab 130 mg group, 50.6% of patients in the ustekinumab 6 mg/kg group, and 48.0% of patients in the placebo group experienced at least one adverse event (AE). The proportion of patients in these groups with at least one serious AE was 3.7, 3.4 and 6.9%, respectively. At week 44 of the maintenance study, at least one AE was reported in 69.2% of patients receiving ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 weeks, 77.3% of patients receiving 90 mg every eight weeks, and 78.9% of patients receiving ustekinumab 90 mg every 8 weeks. who received placebo. The proportion of patients in these groups with at least one serious AE was 7.6, 8.5 and 9.7%, respectively, and with a serious infection 3.5, 1.7 and 2.3%, respectively. Among patients receiving ustekinumab, there were two deaths before week 44 (sudden death associated with bleeding due to esophageal varices and death due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)) and one death after week 44 (a patient with a disorder of normal development suffered cardiac arrest). Cancer developed in seven of 825 patients treated with ustekinumab (one case each of prostate, colon, renal papillary and rectal cancer and three cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer) and one of 319 patients treated with placebo (testicular cancer). Potential opportunistic infections were identified in four patients receiving ustekinumab: cytomegalovirus colitis (in two patients during maintenance therapy), Legionella pneumonia (in one patient during induction), and concomitant ophthalmic and oral herpetic infections (in one patient during treatment ). Cardiovascular events: nonfatal cardiac arrest (in a patient who received ustekinumab during induction and placebo during maintenance), acute myocardial infarction (in a patient who received ustekinumab and died from complications of ARDS), and nonfatal stroke (in a patient who received placebo during induction).

Thus, during treatment with ustekinumab, there was no increase in the risk of developing any AEs compared to placebo, which, according to experts, allows the drug to be used in patients with comorbid conditions or an increased individual risk of AEs on biological therapy [23].

Despite the recent approval of ustekinumab for CD and UC, there is extensive evidence for its use in dermatology and rheumatology.

The incidence of AEs with ustekinumab in the UNIFI study was comparable to that with placebo (AEs, serious AEs, infections, serious infections). This correlates with pooled data on the safety of the drug (phase II/III clinical studies of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, CD).

Analyzed data from 6,280 study patients (3,117 psoriasis, 1,018 psoriatic arthritis, 1,749 CD), based on one year of therapy (i.e., per patient-year), included 4,521 observations versus 674 in the placebo group (829 and 385 patient-years over eight to 16 weeks of follow-up). The combined event rate per 100 patient-years for ustekinumab versus placebo (95% confidence interval) is:

infections 125.4 (122.2–128.7) versus 129.4 (120.9–138.3) at one year follow-up with no increase in infection rates with combination therapy with methotrexate (92.5 (84.2) –101.5) vs 115.3 (109.9–121.0)) with an increase in the incidence of infections when combined with GCS compared with ustekinumab monotherapy (116.3 (107.3–125.9) vs 107.3 ( 102.0–112.8));

rare incidence of major cardiovascular pathologies (0.5 (0.3–0.7) vs 0.3 (0.0–1.1)), oncology (0.4 (0.2–0.6) vs 0.2 (0.0–0.8)) and deaths (0.1 (0.0–0.3) vs 0.0 (0.0–0.4)) [24].

Meta-analysis VS Rolston et al. to assess the incidence of AEs in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of ustekinumab and placebo in the treatment of immunoinflammatory diseases [25] included 30 RCTs involving 16,068 patients. The authors concluded that in the short term (16 weeks), the risk of serious or mild/moderate AEs was not increased with ustekinumab compared with placebo. In addition, there are no differences in the incidence of AEs when comparing high (for IBD) and low doses (for psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis) ustekinumab in the treatment of immunoinflammatory diseases.

The use of ustekinumab for the treatment of UC in real clinical practice

To date, little experience has been accumulated with the use of ustekinumab in real clinical practice. Nevertheless, the results of the first publications are optimistic. The French GETAID study [26] retrospectively included 103 patients with UC. Of these, 70% had previously taken two or more biological drugs, 85% had taken vedolizumab. The majority of patients (90.3%) were given an intravenous induction dose of 6 mg/kg, the rest received 90 mg subcutaneously. All patients received a subcutaneous injection of ustekinumab 90 mg at the eighth week after induction. The primary endpoint was steroid-free clinical remission (assessed by partial Mayo index ≤ 2) at weeks 12–16 of ustekinumab therapy. Clinical response was obtained in 55.4% of patients. 35% of patients achieved the primary endpoint. The absence of rectal bleeding with normal stool frequency was observed in 19.4% of patients. Two patients stopped ustekinumab before the 12–16 week visit and underwent surgery. In multivariate analysis, partial Mayo score >6 at enrollment (18.6 vs 46.7%; p = 0.003) and history of both anti-TNF therapy and vedolizumab use (27.3 vs 80.0%; p = 0.001) were negatively associated with steroid-free clinical remission at weeks 12–16. AEs were registered in 7.8% of patients, serious AEs – in 3.9% of patients.

A German study [27] conducted a retrospective analysis of data from 19 patients with UC who were intolerant or resistant to corticosteroids, purine analogues, anti-TNF therapy, and vedolizumab. All patients received ustekinumab as rescue treatment (6 mg/kg intravenously followed by 90 mg subcutaneously every eight weeks). The primary endpoint was the achievement of clinical remission after one year, defined as ≥ 3 points on the Lichtiger scale (UC activity index) [28].

In five patients, therapy was discontinued due to resistance or side effects. In the remaining 14 patients, the mean UC activity index decreased from 8.5 points (range, 1–12) at baseline to 2 points at one year (range, 0–5.5). The Mayo endoscopic activity score decreased from a median of 2 points (range 1–3, mean 2.3) at baseline to a median of 1 point (range 1–3, mean 1.4) over the course of the year. Clinical remission was achieved in 53% of patients after one year (including five dropouts).

Study results show that in a cohort of patients with UC with prior therapy with multiple biological agents, the use of ustekinumab leads to the achievement of steroid-free clinical remission in 1/3 of patients by 12-16 weeks and in half of patients after a year. Clinical severity and previous use of anti-TNF therapy and vedolizumab are associated with a high risk of ustekinumab failure.

Conclusion

In a phase III study of an IL-12 and IL-23 antagonist in patients with moderate to severe UC [16], ustekinumab was more effective than placebo in achieving clinical remission after eight weeks. This effect was observed both in bionaïve patients and in patients with previous treatment failure with biological agents. The effectiveness of induction therapy has also been demonstrated in a small cohort of patients in real clinical practice [26].

In the UNIFI trial [16], among patients who responded to induction therapy with intravenous ustekinumab and underwent a second randomization, patients assigned to either subcutaneous ustekinumab regimen were more likely to have clinical remission at 44 weeks than patients receiving placebo. For all prespecified primary secondary endpoints in both induction and maintenance therapy, the proportion of patients in the ustekinumab groups was significantly higher than in the placebo group. In real clinical practice, the effectiveness of long-term therapy with ustekinumab for a year has also been shown [27].

The therapeutic goal in patients with UC is to achieve and maintain long-term remission, since the disease is often relapsing [29, 30]. Endoscopic mucosal improvement is associated with better subsequent long-term outcomes [31, 32]. Histological improvement is also associated with better long-term outcomes, including reduction in GCS use and relapse rates [33, 34]. Histoendoscopic mucosal healing, an endpoint assessed in the induction therapy study, was induced by both intravenous doses of ustekinumab and maintained by both subcutaneous doses.

Currently, the safety of the drug can be judged by data on the treatment of patients with other diseases (dermatological, rheumatological and CD) [35–37]. Nevertheless, based on these data and the data obtained in the UNIFI study [16], we can talk about the good tolerability and safety of this drug in most patients.

Currently, ustekinumab is the only drug for the treatment of CD and UC that targets IL-12/23-mediated inflammatory pathways. This type of treatment with a new mechanism of action is intended for patients who are ineffective or intolerant of basic therapy or therapy with anti-TNF drugs and vedolizumab. Clinical trials have shown that ustekinumab can be used effectively and safely in the treatment of UC both in “bionaive” patients and after the failure of biological therapy with other drugs or their withdrawal due to the development of AEs. A drug with a new mechanism of action can be the first line of therapy to achieve long-term effectiveness and sustainable results in patients with a high risk of infectious complications, significant comorbid diseases (class III-IV heart failure, diabetes, demyelinating diseases), in patients with a combination of IBD and skin ( psoriasis) or joint manifestations. Ustekinumab is effective in patients with psoriasiform lesions treated with anti-TNF drugs. Ustekinumab has a favorable safety profile. To date, reactivation of tuberculosis has not been described. In addition, the drug has a convenient administration regimen: a single intravenous induction dose of 6 mg/kg followed by subcutaneous administration of 90 mg once every 12 or eight weeks [23, 38].

To date, there have been no direct comparative clinical trials of ustekinumab and other drugs approved for the treatment of UC (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, vedolizumab). A systematic review and network meta-analysis of the comparative effectiveness of 1-year therapy with ustekinumab and other pharmacological agents in patients with moderate-to-severe UC [39] showed that in the absence of a history of failure of biological therapy, ustekinumab for a year is associated with a higher likelihood of clinical response, remission and endoscopic healing of the mucous membrane. compared to other study drugs. However, further additional studies, longer observations, and expansion of the base of real clinical data of patients with UC are needed.

Drug interactions Stelara

No drug interaction studies have been conducted. A phase III population pharmacokinetic analysis examined the effect of concomitant use of drugs in patients with psoriasis (including paracetamol, ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, metformin, atorvastatin, levothyroxine) on the pharmacokinetics of ustekinumab. No data have been obtained regarding interactions with these drugs when used concomitantly with Stelara. These studies were conducted in at least 100 patients (5% of the study population) who were simultaneously receiving concomitant therapy with these drugs for almost the entire study period (90%). Live vaccines cannot be used simultaneously with Stelara. The safety and effectiveness of Stelara in combination with immunosuppressants and phototherapy have not been studied, so this combination should be used with caution.