The prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is 6%. The median age of onset was 31 years, and the mean age of onset was 32.7 years. Prevalence in children is 3%, in adolescents – 10.8%. The age of onset of the disease in children and adolescents is between 10 and 14. There is evidence that GAD is 2-3 times more common in women than in men, and that GAD is more common in older people. This disorder often goes unrecognized and less than a third of patients receive adequate treatment. The situation is complicated by the fact that it may be necessary to separate GAD in children from GAD in adults.

GAD is associated with functional impairment and decreased quality of life. When initially visiting a doctor, 60-94% of patients with GAD complain of painful physical symptoms and in 72% of cases this is the reason for seeking medical help.

We present to your attention a review translation of clinical guidelines for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, compiled by experts from the Canadian Anxiety Disorders Association. The translation was prepared jointly by the scientific Internet portal “Psychiatry & Neuroscience” and the Psychiatry Clinic “Doctor SAN” (St. Petersburg).

Diagnosis

GAD is characterized by increased anxiety and worry (most days during the past six months) about a variety of events and activities, such as school or work. In addition, GAD is associated with restlessness, muscle tension, fatigue, problems concentrating, irritability and sleep disturbances.

DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing GAD

- Excessive anxiety and worry (anxious anticipation) about a variety of events and activities, such as school or work.

- The person has difficulty gaining control over anxiety

- Excessive anxiety and worry are associated with at least three of the following symptoms, affecting a person most days for at least six months: Restlessness or feeling on edge, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension or sleep disturbances

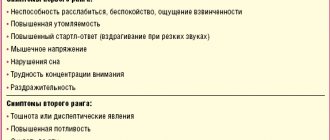

Signs of generalized anxiety disorder

The symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder vary greatly and can vary within the same person over time. A person may notice both improvements and deteriorations in their overall condition as the disease progresses. Stress, shock, negative emotions, and alcohol may not cause acute manifestations of generalized anxiety disorder, but this aggravates the course of the disease, and symptoms may become more severe in the future.

Not every person with generalized anxiety disorder has the same symptoms as another. As discussed, symptoms can vary greatly, but most people with GAD experience a combination of the following emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms.

Emotional symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder

- Constant worries running through your head

- Anxiety is uncontrollable, there is nothing you can do to stop the anxiety

- Intrusive thoughts that create anxiety; You try not to think about them, but you can't

- Intolerance of uncertainty; You must know what will happen in the future

- Widespread (pressing) feeling of apprehension or dread

Behavioral symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder

- Inability to relax and enjoy peace of mind

- Difficulty concentrating

- Quitting activities because you feel depressed

- Avoiding situations that make you anxious

Physical symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder

- Feeling of tension in the body or part of the body, sensation of pain, heaviness, pressure

- Having trouble falling or staying asleep

- Feelings of extreme anxiety or nervousness

- Stomach problems, nausea, diarrhea

Psychological help

Meta-analyses clearly show that CBT significantly reduces GAD symptoms. A small number of studies have compared the effects of CBT and pharmacotherapy, which have shown approximately the same effect size. Individual and group psychotherapy are equally effective in reducing anxiety, but individual psychotherapy may be more effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Psychotherapy intensity was assessed in a meta-analysis of 25 studies. For reducing anxiety, a course of psychotherapy lasting less than eight sessions is as effective as a course lasting more than eight sessions. In reducing anxiety and depression, more intensive courses are more effective than courses with a small number of sessions. Several studies have shown the benefits of ICBT.

The meta-analysis found no significant difference between the effects of CBT and relaxation therapy. However, more recent research suggests limited effectiveness of relaxation therapy. A large RCT found that balneotherapy, a relaxation therapy with spa treatments, was better than SSRIs in reducing anxiety; however, there are doubts about the validity of the study.

The effectiveness of behavioral psychotherapy based on acceptance, metacognitive psychotherapy, CBT aimed at correcting the perception of uncertainty, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has been proven.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy can also provide results, but at the moment there is no clear evidence of its effectiveness.

Adding interpersonal and emotional-process therapy to CBT does not provide significant benefits compared to CBT without the addition. A preliminary conversation before starting a CBT course helps reduce resistance to therapy and improve compliance - this strategy is especially useful in severe cases.

Service price

- HOSPITAL Day hospital5 000

- Day hospital with intensive care8,000

- 24-hour hospital (all inclusive, cost per day) 12,000

- 24-hour hospital (all inclusive, cost per day). Single occupancy24,000

- 24-hour hospital (all inclusive, cost per day). Single occupancy in a superior room 36,000

- Primary family counseling for relatives of patients undergoing inpatient treatment free of charge

- Group psychotherapy for relatives of patients undergoing inpatient treatment free of charge

- Group psychotherapy for 24-hour and day hospital patients free of charge

- Individual post for a hospital patient (if indicated)6,000

Combination of psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment

Few data are available on the use of combinations of psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment. A meta-analysis showed that the combination of pharmacological treatment with CBT was more effective than CBT alone when comparing results immediately after treatment, but not after six months. Data are available from studies comparing the combination of diazepam or buspirone plus CBT with CBT alone. The small number of studies comparing pharmacotherapy with pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy has produced conflicting results.

There is currently no rationale for combining CBT with pharmacotherapy. But, as with other anxiety disorders, if the patient does not improve with CBT, the use of pharmacotherapy is recommended. Likewise, if pharmacotherapy does not improve, then CBT can be expected to help. Meta-analyses and several RCTs suggest that psychotherapy benefits are maintained 1-3 years after treatment.

Causes

An important factor determining the possible development of an anxiety disorder is predisposition. Approximately 20% of people are born with a special mood in the nervous system, which predetermines such a personality trait as increased anxiety. These individuals are at high risk of developing anxiety disorders. The following conditions can trigger painful anxiety:

- Overwork : chronic stress, lack of sleep, starvation and exhaustion.

- Mental trauma.

- Hormonal disorders : hyperthyroidism, hypothalamic syndrome, increased activity of the adrenal glands.

- Diseases of the nervous system : encephalopathy, infections of brain tissue.

- Poisoning . Abuse of alcohol, drugs, sleeping pills or sedatives.

- Mental disorders : phobias, depression, neuroses, psychosomatic diseases, schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Pharmacological treatment

SSRIs, SSRIs, TCAs, benzodiazepines, pregabalin, quetiapine XR have been proven effective in the treatment of GAD.

First line

Antidepressants (SSRIs and SSRIs): RCTs show the effectiveness of escitalopram, sertraline and paroxetine, as well as duloxetine and venlafaxine XR. The effectiveness of SSRIs and SSRIs is the same. There is evidence that escitalopram is less effective than venlafaxine XR or quetiapine XR.

Other antidepressants: There is evidence that agomelatine is as effective as escitalopram.

Pregabalin: Pregabalin is as effective as benzodiazepines (level 1 evidence).

Second line

Benzodiazepines: Alprazolam, bromazepam, diazepam and lorazepam have been shown to be effective (level 1 evidence). Although the level of evidence is high, these drugs are recommended as second-line treatment and usually for short-term use due to side effects, dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

TCAs and other antidepressants: Imipramine is as effective as benzodiazepines in the treatment of GAD (level 1 evidence). But due to side effects and potentially toxic overdose, imipramine is recommended as a second-line treatment. There is little data on bupropion XL, but there is a study in which it was shown to be as effective as escitalopram (first-line agent), so it can be used as a second-line agent.

Vortioxetine, a so-called serotonin modulator, acts on different serotonin receptors. Research on the effectiveness of vortioxetine is inconsistent, but there is evidence to support its use for GAD.

Quetiapine XR: Quetiapine XR has proven efficacy and is equivalent to that of antidepressants. But quetiapine is associated with weight gain, sedation, and a higher rate of treatment discontinuation due to side effects than antidepressants. Because of problems associated with tolerability and safety of atypical antipsychotics, this drug is recommended as a second-line treatment for patients who cannot take antidepressants or benzodiazepines.

Other drugs: Buspirone has been shown to be as effective as benzodiazepines in several RCTs. There is insufficient data to compare buspirone with antidepressants. Due to its lack of effectiveness in clinical practice, buspirone should be classified as a second-line drug.

Hydroxyzine has shown efficacy close to that of benzodiazepines and buspirone, but there is insufficient clinical experience with the use of this drug for GAD.

Third line

Third-line drugs include drugs with poorly studied efficacy, side effects, and rarely used as a primary treatment for GAD.

Additional drugs

The adjunctive strategy has been studied in patients who have not responded adequately to SSRI treatment and may be used in cases of refractory GAD.

Second-line add-on drugs: Pregabalin, as an adjunct to the main drug, has been shown to be effective in treating patients who have not responded to previous treatment (level of evidence: 2).

Third-line add-on drugs: A meta-analysis showed no improvement with atypical antipsychotics as add-on drugs, but did show an increase in treatment failure. Studies of the effectiveness of risperidone and quetiapine as adjunctive agents show conflicting results.

Due to weak evidence of effectiveness, risk of weight gain, and metabolic side effects, atypical antipsychotics should be reserved for refractory cases of GAD and, with the exception of quetiapine XR, used only as an adjunct to the primary drug.

A drug | Level of evidence |

| SSRIs | |

| Escitalopram | 1 |

| Paroxetine | 1 |

| Sertraline | 1 |

| Fluoxetine | 3 |

| Citalopram | 3 |

| SSRI | |

| Duloxetine | 1 |

| Venlafaxine | 1 |

| TCA | |

| Imipramine | 1 |

| Other antidepressants | |

| Agomelatine | 1 |

| Vortioxetine | 1 (conflicting data) |

| Bupropion | 2 |

| Trazadone | 2 |

| Mirtazapine | 3 |

| Benzodiazepines | |

| Alprazolam | 1 |

| Bromazepam | 1 |

| Diazepam | 1 |

| Lorazepam | 1 |

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Pregabalin | 1 |

| Divalproex | 2 |

| Tiagabine | 1 (negative result) |

| Pregabalin as an adjunctive drug | 2 |

| Other drugs | |

| Buspirone | 1 |

| Hydroxyzine | 1 |

| Pexacerfont | 2 (negative result) |

| Propranolol | 2 (negative result) |

| Memantine | 4 (negative result) |

| Pindolol as an additive drug | 2 (negative result) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | |

| Quetiapine | 1 |

| Quetiapine as an add-on drug | 1 (conflicting data) |

| Risperidone as an add-on drug | 1 (conflicting data) |

| Olanzapine as an add-on drug | 2 |

| Aripiprazole as an add-on drug | 3 |

| Ziprasidone as monotherapy or in combination | 2 (negative result) |

| First line: Agomelatine, duloxetine, escitalopram, paroxetine, pregabalin, sertraline, venlafaxine Second line: Alprazolam*, bromazepam*, bupropion, buspirone, diazepam, hydroxyzine, imipramine, lorazepam*, quetiapine*, vortioxetine Third line: Citalopram, divalproex, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, trazodone Additional drugs (second line): Pregabalin Additional drugs (third line): Aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone Not recommended as adjunct drugs: Ziprasidone Not recommended: Beta blockers (propranolol), pexacefront, tiagabine *These drugs have their own mechanisms of action, effectiveness and safety profile. Benzodiazepines are best used as second-line drugs in most cases unless there is a risk of abuse; It is better to postpone bupropion XL for later. Quetiapine XR is a good choice in terms of effectiveness, but given the metabolic problems associated with atypical antipsychotics, it is best reserved for patients who cannot be prescribed antidepressants or benzodiazepines. |

Publications in the media

Emotions constitute an integral component and manifestation of human life. There are only two types of positive emotions: joy and interest. Negative emotions have a wider spectrum than positive ones and are divided into biological (anxiety, fear, suffering, anger and their derivatives) and social (shame, guilt, fear of losing one’s self). A special place among them is occupied by anxiety, which is one of the most ancient evolutionary mechanisms. Its biological significance is that it, as an analogue of an active-defensive reaction, provides the body with preparedness for action in a situation of stress. According to R. May [7], “anxiety is fear in a situation where a value is under threat, which, according to a person’s feeling, is vitally important for the existence of his personality.” In this context, anxiety is natural, adequate, and useful. However, under a number of objective and subjective conditions, anxiety becomes excessively expressed, loses its adaptive nature and is considered pathological (

). Transforming from normal to pathological, anxiety becomes the basis for the formation of anxiety disorders (AD).

Etiopathogenesis and epidemiology of TR

Currently, during times of stress and overload, the prevalence of TD in the population is very high [1, 10]. According to foreign literature, at one time 9% of the world's population suffers from some kind of TR, and almost 25% of people suffer from TR throughout their entire life.

The biological and psychological prerequisites for the formation of TR are considered [2]. Psychological aspects of etiopathogenesis are presented within the framework of various psychological theories. In particular, psychoanalytic theory views anxiety as a signal of the emergence of an unacceptable, forbidden need or impulse that prompts the individual to unconsciously prevent its expression. From the standpoint of behaviorism, anxiety and, in particular, phobias initially arise as a conditioned reflex reaction to painful or frightening stimuli. Cognitive psychology focuses on erroneous and distorted thought patterns that precede the onset of anxiety.

Biological theories take the biological criterion, i.e., the specific state of the brain substrate, as the basis for defining the concept. In this paradigm, any TR is considered as a consequence of cerebral pathological changes, the identification of which is associated with further improvement of diagnostic technologies. In particular, studies of the bioelectrical activity of the brain of patients with TD show differences in the spatial-frequency characteristics of the electroencephalogram (EEG) in individuals with increased levels of anxiety [3, 5]. A study of the level of cerebral metabolism suggests that the basis of the brain support for reactive anxiety is a system whose most stable links are cerebral structures such as the superior parietal associative cortex, the parahippocampal gyrus, the thalamus and caudate nucleus, and the amygdala [2, 12].

The peculiarity of the modern approach to the study of anxiety is the idea of its multifactorial nature, based on the recognition of the unity of the biological, psychological and social components of anxiety.

Classification of anxiety disorders

Existing classifications of TD involve the formation of independent rubrics based on the understanding of anxiety not as a syndrome, but as a separate diagnostic unit. Anxiety and TD are considered in the two most widely used diagnostic systems - ICD-10 and the American DSM-IV-TR.

ICD-10 does not use the traditional differentiation between neuroses and psychoses, which was used in ICD-9. However, the term "neurotic" is retained in the title of the large group of disorders F40-F48 "Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders."

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR (2000) used the term “neurosis” to describe anxiety disorders before the classification was reissued in 1980. However, in the future, a trend of increasing clinical “fragmentation” of TD began to take place, which was reflected in later classification systems of behavioral and mental disorders.

Clinical characteristics of anxiety disorders

The group of TD includes several rather heterogeneous diseases, connected by one common feature - a high level of anxiety, which is persistent in nature, may or may not be limited to any specific circumstances (fixed or unfixed, personal and situational).

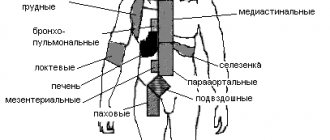

Clinically, TR is manifested by mental and somatic (vegetative) symptoms, an important distinguishing feature of which is their polysystemic nature.

The most common mental manifestations of TR are:

- fears (worry about future failures, feelings of excitement, difficulty concentrating, etc.);

- worrying about little things;

- irritability and impatience;

- feeling of tension, stiffness;

- fussiness;

- inability to relax;

- feeling nervous or on the verge of a breakdown;

- inability to concentrate;

- memory impairment;

- fast fatiguability;

- fears;

- obsessive thoughts, images.

Autonomic (somatic) manifestations of anxiety include:

- sweating, cold and wet palms;

- dry mouth;

- feeling of a “lump” in the throat;

- feeling of lack of air;

- muscle tension and pain;

- nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain;

- dizziness;

- fainting state;

- decreased libido, impotence;

- muscle tension and pain;

- cardiopalmus;

- hot or cold flashes.

A characteristic property of anxiety is not only the anticipation of a particular danger, but also the motivation to search for and specify this danger, which leads to the formation of certain syndromes. The formation of one or another clinical syndrome, i.e., one or another variant of TR, depends on the path followed by the specification (realization) of anxiety.

Characteristics of the main variants of anxiety disorders

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (F41.1) is characterized by anxiety that is generalized and persistent, not limited to any specific environmental circumstances, and does not even occur with a clear preference in those circumstances (i.e., is “unfixed”).

To make a diagnosis, primary anxiety symptoms must be present for at least six weeks. Most often they serve in this capacity:

- restlessness, fussiness, or impatience;

- fast fatiguability;

- disorder of concentration and memory;

- irritability;

- muscle tension;

- sleep disturbance.

Diagnostic criteria for GAD are less clear than for other variants of GAD, and are rather based on the principle of exclusion. According to most researchers, GAD does not represent a single diagnostic category, but rather reflects a special disturbing phenomenon that occurs with different diagnoses.

The remaining TRs, classified under other headings and subcategories, are essentially determined by the above criteria (most of them or only part) and additional criteria that determine the specifics of a particular TR.

The main feature of panic disorder (F41.0) is periodically recurring panic attacks that occur spontaneously, suddenly, without any visible connection with external stimuli (“like a bolt from the blue”), last 5–30 minutes and are accompanied by symptoms such as shortness of breath, palpitations , dizziness, choking, chest pain, trembling, increased sweating and fear of dying or going crazy. Attacks often occur in a situation where patients are restricted in their freedom of movement or in a room from which they cannot escape and where they cannot get help.

Panic disorder is often accompanied by agoraphobia. Currently, this term is interpreted more broadly than before, and includes fear not only of open spaces, but also of any situations from which it is not possible to immediately get out and return to a safe place. Although agoraphobia is considered a separate disorder, it often serves as a defense mechanism for panic disorder: by staying at home or leaving it only with an accompanying person, sufferers thereby avoid stress, reducing the likelihood of an attack.

Phobic anxiety disorder (F40) clinically manifests itself as overvalued fears that are not justified by a specific threat or do not correspond to its level of significance.

The following are the characteristic properties of phobias:

- expressed and persistent or unreasonable fear associated with the presence or expectation of a specific object or situation;

- immediate phobic reaction to an alarming stimulus;

- the patient’s awareness of the excessiveness and irrationality of fear;

- avoidance of phobic situations;

- pronounced distress associated with awareness of the phobia.

The topics of phobias are varied. One of the most common types of phobias - nosophobia (fear of illness, for example, cancerophobia) - is often provoked by the illness of someone you know. Even a thorough medical examination rarely brings relief.

Agoraphobia (F40.0) is specific to the fear of being in a crowd of people, in a public place, or on any trip, especially on your own. As mentioned earlier, agoraphobia can accompany panic attacks, but can also occur without them.

Social phobia (F40.1) - severe fear of being the center of attention or fear of behaving in a way that causes embarrassment or humiliation in certain situations, such as socializing or eating in public, public speaking, meeting familiar faces in public, visiting public restrooms, being in small groups (e.g., parties, meetings, classrooms), etc.

The defining criterion for specific (isolated) phobias (F40.2) is fear within a strictly limited situation or strictly defined objects (heights, snakes, spiders, airplane flights, etc.). As with social phobias, avoiding significant situations in some cases helps patients adapt quite successfully to everyday life.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42) includes compulsions, which often lead to the formation of obsessive actions and rituals (compulsions). Obsessions are ideas, thoughts, or impulses that persistently and persistently pursue a person and that are perceived as painful and unpleasant, such as blasphemous thoughts, thoughts about murder, or thoughts about sex. They are characterized by the following signs:

- perceived as intrusive and inappropriate;

- are not the result of excessive worry about real problems;

- accompanied by an unsuccessful desire to suppress, avoid, ignore them, or neutralize them with other thoughts or actions;

- are recognized by the patient as a product of his own psyche.

Compulsivity is a repetitive, goal-directed, and intentional behavior that occurs as a reaction to compulsions in order to neutralize or prevent psychological discomfort.

Examples include obsessive thoughts about dirt and pollution, leading to compulsive washing and avoidance of “polluting” objects, pathological counting, and compulsive checking, such as repeatedly checking that the gas is off, or returning to the same street to make sure no one is there. crushed, etc.

Post-stress anxiety within post-traumatic stress disorder (F43.1) develops after life-threatening situations or disasters (military operations, nuclear power plant accident, car accident, fire, flood, rape). Characterized by persistent painful memories, increased excitability, irritability and outbursts of anger, sleep disturbances and nightmares, including pictures of the experienced situation, feelings of loneliness and mistrust, a feeling of inferiority, avoidance of communication and any activities that may remind of the events that occurred.

Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder (F41.2) is diagnosed when the patient has symptoms of both anxiety and depression, but neither one nor the other is clearly dominant or severe.

Within the framework of specific personality disorders (F60) (it should be remembered that pronounced personality disorders are psychopathy familiar to the Russian-speaking reader), anxious (“avoidant”, “avoidant”) personality disorder (F60. 6). To some extent, it resembles a sensitive type of psychopathy, which was not always distinguished in Russian classifications. From early childhood, patients are characterized as timid, shy people with low self-esteem. An exaggerated fear of arousing even a slight critical attitude leads them to avoidant behavior.

In its clinical picture, dependent personality disorder (F60.7) is very close to the anxious type. It, like the previous one, was also borrowed from the DSM and was absent from classical Russian and German psychiatry. Self-doubt, fear of displaying any noticeable reactions (especially sexual and aggressive) are combined with expressed anxiety, fear of being abandoned by a significant person.

Features of the manifestation of anxiety in childhood are:

- prevalence of obsessive-phobic disorders;

- more pronounced somatization of anxiety;

- pronounced behavioral disorders: limited contact, fussiness, restlessness, aggressiveness;

- self-doubt, low self-esteem;

- constant need for adult support;

- the presence of specific variants of anxiety disorders in children.

Specific TDs of childhood are presented in the heading F93 “Emotional disorders of childhood.” Most of them are essentially exaggerations of normal trends in the process of development, rather than qualitatively new phenomena. An example is separation anxiety disorder in childhood (F93.0). Such children do not develop skills of independent behavior and the fear of separation acquires exaggerated proportions. Anxiety in a child can take the following forms:

- persistent, unrealistic fear of misfortune that could happen to the main person in his immediate environment, or fear that his parents will leave him and not return;

- an unrealistic fear that some untoward event will separate the child from the person for whom great affection is felt;

- refusal to go to sleep alone or away from home for fear of losing a significant person;

- recurring nightmares about separation;

- reappearance of somatic disorders in situations related to separation;

- recurrent distress (anxiety, crying, irritation, apathy, withdrawal, etc.).

The Pediatric Phobic Anxiety Disorder rubric can only be used for developmentally specific fears that meet the criteria of the F93 rubric:

- onset at a developmentally appropriate age;

- the degree of anxiety is excessively expressed and causes a clear decrease in social adjustment;

- anxiety is not part of a more generalized disorder.

Childhood social anxiety disorder (F93.2) is used only for disorders that occur before age 5 years and do not correspond to typical age-specific presentations. Noteworthy is the pronounced difference between behavior at home and in non-family social situations, which is accompanied by problems of social functioning.

Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

Experience with patients suffering from TD inevitably leads clinicians to the conclusion that an integrated approach combining psychotherapy, psychopharmacotherapy and social-environmental influence is maximally effective (

).

The main method in a complex therapeutic complex for TR is psychotherapy [4, 11]. Currently, a psychotherapist has a large arsenal of tools at her disposal, ranging from simple ones that solve the problem of symptomatic improvement to complex ones aimed at resolving the patient’s internal conflicts. Most psychotherapy regimens are based on the assumption that anxiety is caused by an exaggerated assessment of the threat or an incorrect interpretation of one's own state of increased activation. In this case, either the external danger is overestimated or one’s own abilities to cope with it are underestimated. Anxious fears and a feeling of helplessness arise, in which increased attention is paid to one’s internal state. Increased alertness leads to a narrowing of attention and a decrease in its concentration, as well as to violations of self-control and correct response. The most important goal of psychotherapy is to gradually bring patients to an awareness of the essence of their psychological conflict and then to a gradual modification of previous inadequate patterns and attitudes and, ultimately, the development of a new, more harmonious and flexible system of views and relationships, more mature adaptation mechanisms, restoration of self-control and adequate response. The content of the main psychotherapeutic methods effective in working with anxiety disorders is given in

.

All of the above methods are equally effective for various types of TR, however, it is worth noting that certain techniques are more preferable and, in a certain sense, specific for specific forms of TR (

).

Psychopharmacotherapy plays a special role in the treatment of TR (

). Currently, there is a rich arsenal of anti-anxiety drugs that can influence not only mental, but also somatic manifestations of anxiety.

The formation of anxiety is based on an imbalance of certain mediators: serotonin, norepinephrine and GABA. Anti-anxiety drugs mainly realize their effect through these mediator systems. Among GABAergic anxiolytics, the leading place is occupied by benzodiazepine tranquilizers. The main advantages of benzodiazepine anxiolytics are the rapid and real achievement of a therapeutic effect. Among the disadvantages of treatment with benzodiazepines, the following should be mentioned: “recoil” syndrome (rapid resumption or transient increase in symptoms after discontinuation of the drug), the risk of addiction and the formation of drug dependence, impaired cognitive functions (attention, concentration, memory), and impaired coordination. Therefore, benzodiazepine drugs should not be taken for longer than 2–4 weeks.

In connection with the above “benzodiazepine” problems, a new generation of non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics is being widely introduced into clinical practice. These include, in particular, blockers of histamine H1 receptors: tofisopam (Grandaxin), which has an anxiolytic effect, is a psychovegetative regulator, and also does not have a sedative and muscle relaxant effect, and hydroxyzine (Hidroxyzine, Atarax), which has a rapid onset of effect, absence of addiction and drug dependence, does not impair cognitive functions, has antipruritic and antiemetic effects.

Other non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics include the azapirone drug buspirone (Spitomin) and Afobazole (prevents the development of membrane-dependent changes in the GABA receptor).

Tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and dual-acting antidepressants act on anxiety through the serotonergic systems.

The first-line drugs for the treatment of anxiety disorders are benzodiazepine tranquilizers and SSRIs; tricyclic antidepressants and non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics are considered second-line drugs.

In some cases, a positive effect in the treatment of anxiety is achieved with the use of antipsychotics - thioridazine (Sonapax), sulpiride (Eglonil), tiapride (Tiaprid), etc. However, it should be remembered that when prescribing antipsychotics, weakness, decreased blood pressure, menstrual irregularities, weight gain, colostrum secretion, decreased libido.

Beta-adrenergic blockers (such as propranolol and atenolol) are especially effective when the autonomic component of TR is pronounced, as they block the physical symptoms of chest pain, throat constriction and shortness of breath without having a sedative (relaxing) effect.

In some cases, psychotropic drugs may be poorly tolerated by patients due to side effects, which ultimately neutralizes their therapeutic effectiveness. Official herbal preparations, which have significantly fewer side effects, can be considered as an alternative therapy or used to enhance the effectiveness of prescription drugs. The main indication for the use of this category of drugs is short-term subsyndromal or “undeveloped” (mild) anxiety disorders.

Among the herbal medicines used by clinicians to treat subthreshold anxiety, the drug Novo-Passit has become widespread, which has shown its effectiveness, the possibility of use in a wide variety of age groups [6, 8], the absence of any side effects, high anxiolytic activity and, finally, , which is very important, its availability. The active components of the drug are dry extracts of medicinal plants with pronounced sedative activity (hops, St. John's wort, lemon balm, passionflower, elderberry, valerian, hawthorn) and guaifenesin, which has a pronounced anxiolytic effect.

Due to its unique composition, Novo-Passit is often prescribed to children and adults with various forms of anxiety disorders. The sedative and anxiolytic effect of the drug helps eliminate anxiety and associated autonomic symptoms: sleep disorders, muscle tension, headaches and asthenia. The drug is non-toxic, safe and non-addictive.

Homeopathic anti-anxiety medications have become another alternative to medications. These drugs include Tenoten, which contains fine regulators - antibodies to the S-100 protein contained in the parts of the brain responsible for an adequate emotional response. As a result, its GABA-mimetic effect is realized and GABAergic neurotransmission is restored. The clinical effect is manifested by a decrease in anxiety and improvement in cognitive functions [9].

The choice of psychotropic drug depends on the characteristics of the TR:

- degree of severity of anxiety level;

- duration of the disease (acute, chronic);

- type of course (paroxysmal or permanent disorders).

As the clinical picture becomes more complex and anxiety becomes chronic, priority is increasingly given to antidepressants or combination therapy.

Among other drugs used in the treatment of TR, one can note drugs that improve hemodynamic and metabolic processes in the central nervous system (piracetam (Nootropil), gamma-amino-butyric acid (Aminalon), for children - hopantenic acid (Pantogam)). These drugs, having a direct activating effect on the integrative mechanisms of the brain, stimulate cognitive processes, increase the brain’s resistance to “aggressive” influences, improve cortico-subcortical connections, facilitate the transfer of information between the hemispheres, and improve synaptic transmission in brain structures. In solving this problem, the drugs Neuromultivit and Enerion, which act on the structures of the reticular formation and have a stimulating effect, have proven themselves well.

Currently, material is accumulating in world clinical practice indicating that specially selected “afferent (sensory) inflows” help optimize autonomic regulation in various pathological conditions, in particular in TR (Gudzzetta CE, 1989; Malyarenko T.I. and co-authors, 1998, 2000; Zavyalov A.V., 2000; Govsha Yu.A., 2003). To solve these problems, acoustic (music), olfactory (smells), visual and other sensory inputs are used, as well as combined forms of psychosensory influence in the complex therapy of TD. In the complex of TR therapy, other methods based on physiogenic effects are also used: reflexology, massage.

Based on the above, it seems important to increase the awareness of general specialists about the features of diagnosis and treatment of TR. Modern approaches to the treatment of TD are based on an integrative approach, combining psychotherapy, psychopharmacotherapy and social-environmental influence. ЃЎ

Maintenance pharmacological therapy

A meta-analysis showed that long-term use of SSRIs (6–12 months) was effective in preventing relapse (odds ratio for relapse = 0.20).

Relapse after 6-18 months of duloxetine, escitalopram, paroxetine and venlayaxin XR was observed in 10-20% of cases, compared with 40-56% in the control group. Continuing pregabalin and quetiapine XR also prevents relapse after 6-12 months.

Long-term RCTs have shown that escitalopram, paroxetine and venlafaxine XR help maintain benefit over six months.

Symptoms

All manifestations of anxiety disorder can be divided into three groups:

- Mental : feelings of fear, anxiety, panic, a feeling of impending disaster, obsessive thoughts of unpleasant content (fear for health, fear of death, fear of losing control, etc.), increased attention to one’s internal state.

- Physiological symptoms : insomnia, palpitations, shortness of breath, heaviness or discomfort in different parts of the body, fluctuations in pulse and blood pressure, dry mouth, sweating, urge to urinate, etc.

- Changed behavior : restlessness, reaching the point of throwing and trying to run, or immobility (stupor), forced posture during a panic attack; searching for non-existent diseases in oneself; constant “listening to yourself”; avoiding places and situations where anxiety occurred.

Why does the disorder occur?

Doctors cannot give an exact answer to the question posed - they do not know the reliable mechanisms of occurrence of the described pathological process. But, some scientists argue that it has a cognitive origin, that is, obsessive experiences appear due to a distortion of a person’s stereotypical thinking.

According to A. Beck, an American psychotherapist, professor at the University of Pennsylvania and creator of cognitive psychotherapy, anxiety is a normal reaction to upcoming changes and danger, but there are individuals whose assessment of the development of the situation is distorted due to low self-esteem. It is because of self-doubt that they subconsciously believe that they will not be able to cope with a dangerous situation, as a result of which this pathology develops.

Treatment methods for disorders

The described type of neurosis can be successfully corrected after diagnostics using special tests, a detailed survey and some psychometric analyses. Most often, two methods are used to get rid of this condition:

– psychotherapy,

- use of medications.

Psychotherapy

Today, the most progressive and effective therapeutic methods are cognitive-behavioral and metacognitive psychotherapy. These techniques primarily pay attention to a person’s thoughts, which force him to see the whole world primarily in a threatening and negative light.

Also, both approaches help develop new skills for solving and overcoming your problems, which reinforce fear. During the classes, the patient learns to record his thoughts, separate real and imaginary threats, concentrate attention, manage his emotions, rationally perceive the world around him and steadfastly endure all the uncertainties and worries that cause significant factors.

Another psychological approach that shows good effectiveness is the relaxation technique. In this case, the psychologist teaches the patient, during the next attack of anxiety, to imagine calming situations that cause both psychological and muscular relaxation, which brings relief and calm.

Drug therapy

In addition to psychoanalysis, some are prescribed additional medications. The primary pharmacological line is the prescription of antidepressants and benzodiazepines. The drugs have anti-anxiety, sedative and muscle relaxant effects, which eliminate anxiety, sleep disorders and reduce depression. Most often, doctors prescribe paroxetine, escitalopram, sertraline, diazepam, lorazepam and phenazepam. Some of these drugs can be taken for long courses of up to one year, which is discussed with the treating doctor.

However, many of the above tablets also have side effects, so they should only be prescribed by the attending physician, based on the results of tests and screenings.

In addition to the two generally accepted methods, there are alternative ones. Among them, the biofeedback method, breathing and sports gymnastics, as well as various types of rehabilitation and relaxation are common.

How to get rid of it yourself

Few people manage to get rid of anxiety disorder on their own. This is a disease, it needs to be treated, and not wait until it “goes away on its own” or try to fight it on your own. But there are many ways to temporarily reduce anxiety, stop a panic attack, reduce tension and feelings of fear. These include: auto-training, water treatments (cold shower in the morning, warm bath in the evening), giving up alcohol, physical exercise (“intensive exercise”), normalizing the daily routine and sleep-wake cycle, spiritual development, personal growth, etc.

See advice from psychologists on how to cope with anxiety and panic HERE.